Reading between the lions: A history of the New York Public Library

Photo via Jeffrey Zeldman/Flickr

The New York Public Library first roared into existence on May 23, 1895, educating and inspiring countless millions, free of charge. The Library’s 92 locations include four research divisions and hold over 51 million items. Out of all these tomes, the greatest tale might be Library’s own history: Founded by immigrants and industrialists, it was equally admired by William Howard Taft and Vladimir Lenin; open to all, it has counted among its staff American Olympians and Soviet spies; dedicated to intellectual exploration and civic responsibility, it has made its map collection available to buried treasure hunters and Allied Commanders; evolving with the city itself, it has made branch locations out of a prison, a movie theater, and most recently, a chocolate factory. The history of the New York Public Library is as vital and various New York itself, so get ready to read between the lions.

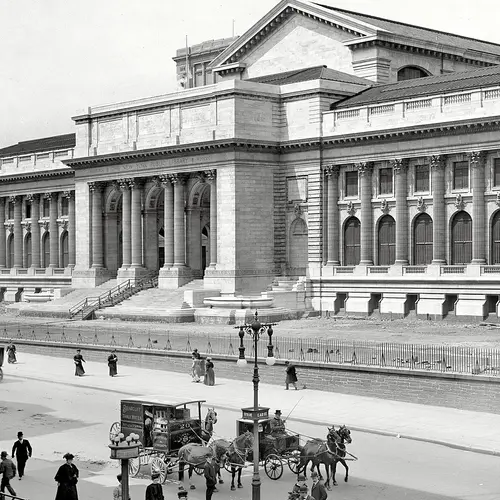

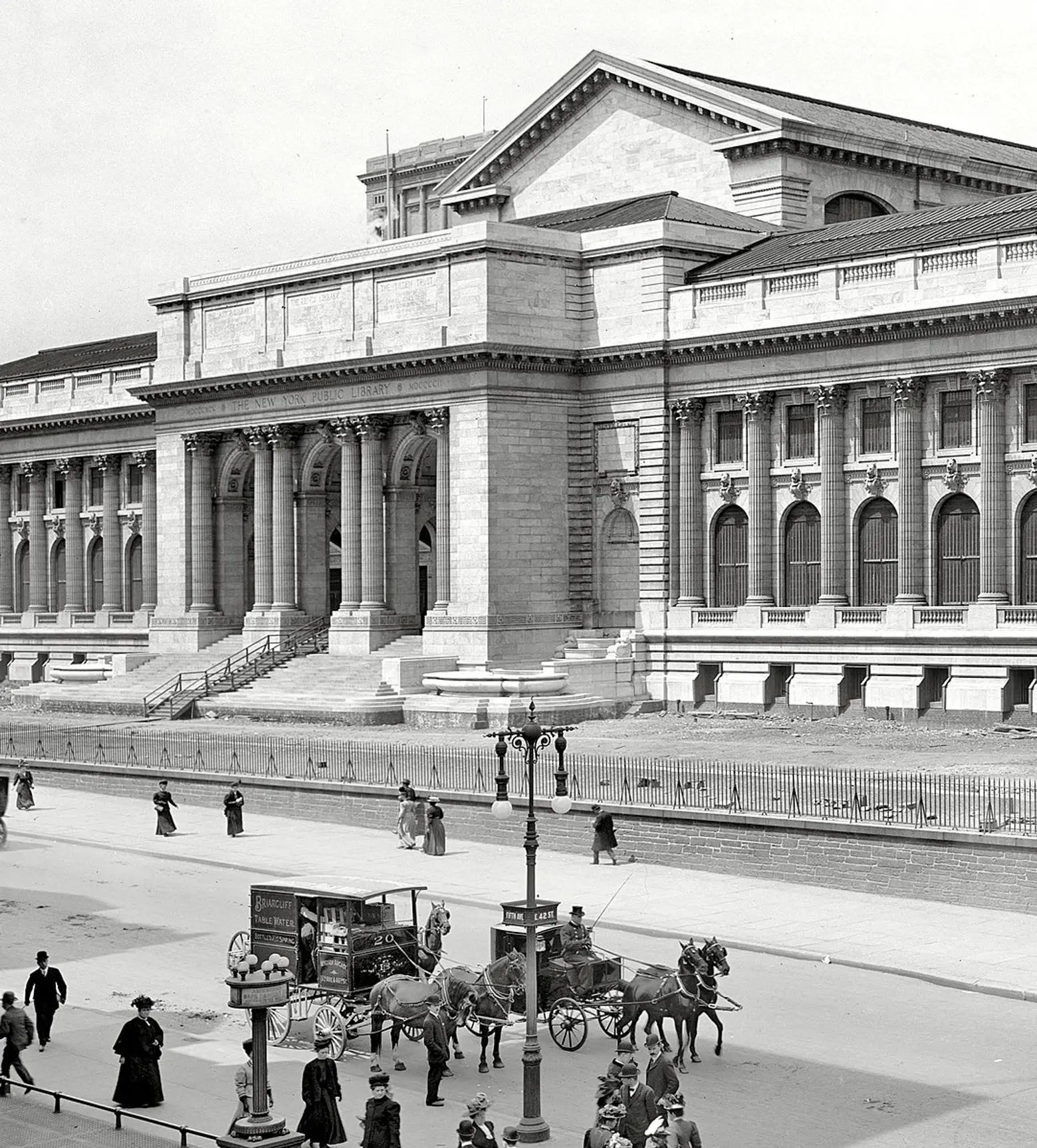

The Central Branch under late-stage construction in 1908, via Wiki Commons

The Central Branch under late-stage construction in 1908, via Wiki Commons

When NYPL’s Central Branch opened on 42nd Street and 5th Avenue on May 23rd, 1911. After 16 years of planning, it was the largest marble structure ever built in the United States. This extraordinary grandeur reflected New York’s aspirations at the turn of the 20th Century. Samuel Tilden, the 25th Governor of New York State, saw New York emerging as a world city, and believed it needed world-class public institutions to match. He bequeathed about $2.4 Million to “establish and maintain a free library and reading room in the city of New York.” His institution would be on par with the British Library, the Bibliotheque Nationale, and, New Yorkers hoped, it would the put stately the Boston Public Library to shame.

The Central Branch in the 1910s, via Library of Congress

The Central Branch in the 1910s, via Library of Congress

Tilden’s library needed a collection to match. Luckily, New York already had two major public research collections. The Astor Library, John Jacob Astor’s legacy, built on Lafayette Street in 1854 in what is now the Public Theater, was a scholarly reference collection; The Lenox Library, founded by the bibliophile philanthropist James Lenox in 1877, held special literary treasures and galleries of painting and sculpture.

At the Astor and Lennox Libraries, books didn’t circulate. This cloistered approach reflecting the Astor Chief Librarian’s idea that “A free library of circulation is a practical impossibility in a city as populous as New York. In the first place, it could never supply one out of a hundred of the demands in the case of popular books; and in the next place, it would be dispersed to the four winds within five years.” When the Astor and Lenox Libraries merged with The Tilden Trust on May 23rd 1895 to create the New York Public Library, it seemed NYPL would follow the same course, with items only available on-site.

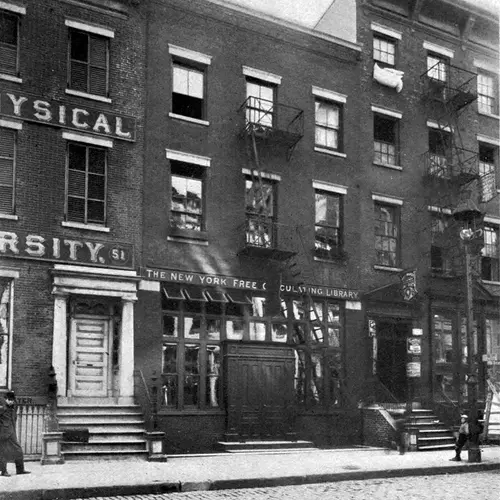

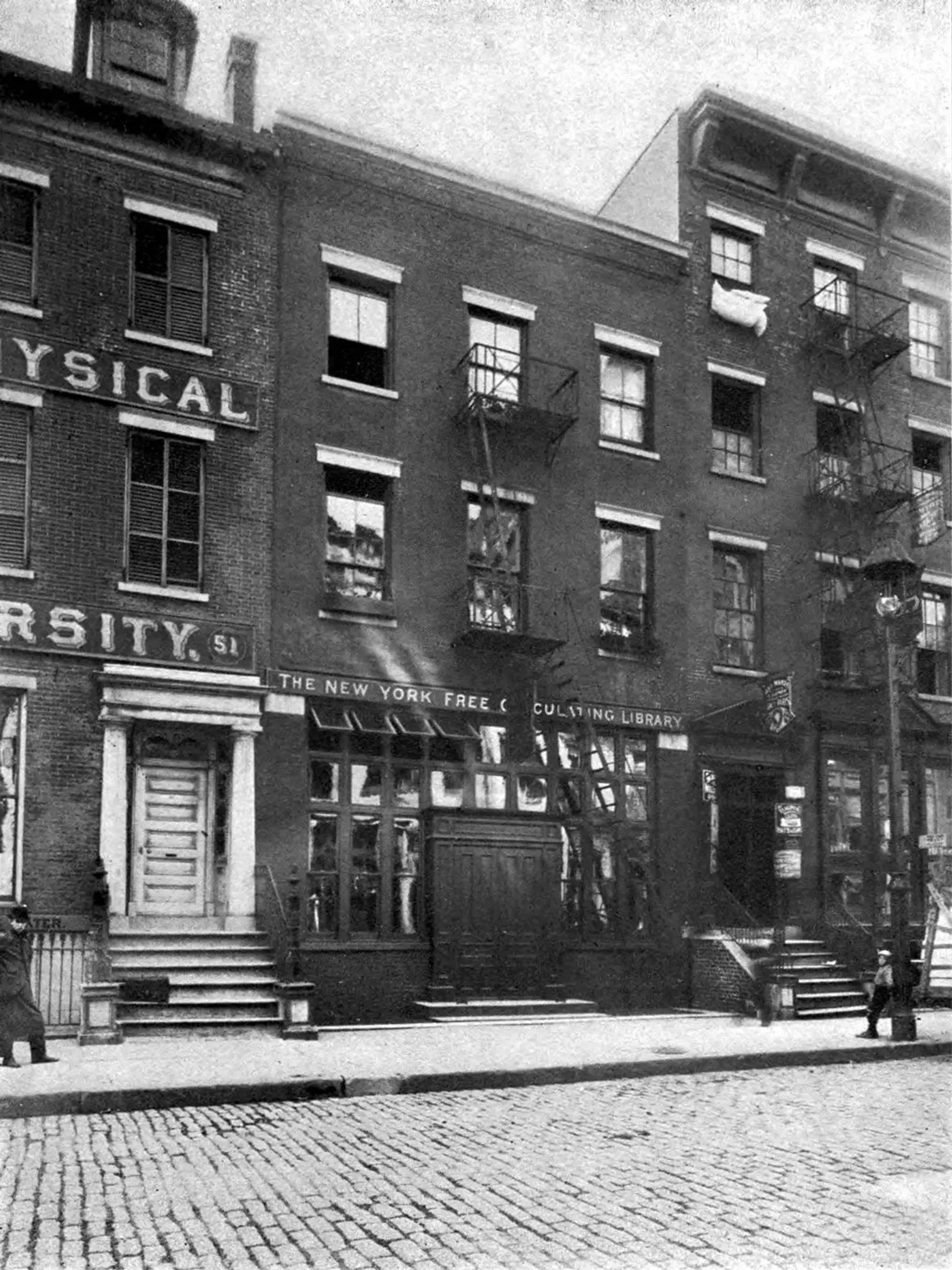

49 Bond Street (opened 1883) where the first branch of the NYFCL settled for most of its existence, via Wiki Commons

49 Bond Street (opened 1883) where the first branch of the NYFCL settled for most of its existence, via Wiki Commons

Thankfully, The New York Free Circulating Library proved books could fly off the shelves. Founded by a group of women in a Grace Church sewing class in 1879, the New York Free Circulating Library attracted patrons “from lower Broadway to 120th street,” who packed the library, and spilled out to block the sidewalk. The NYFCL met this need-to-read using rented rooms on Bond Street to “circulate books among the very poor,” and furnish “free reading to the people of New York City.” The NYFCL eventually supported 11 branches and a traveling library service.

The New York Free Circulating Library joined NYPL as the Circulation Department in February 1901. A month later, Andrew Carnegie made that mission manifest throughout New York, offering the city $5.2 million to construct 67 branch libraries that would be privately financed and publicly maintained.

Thirty-nine Carnegie Libraries became part of the New York Public Library System, and Carnegie’s public-private partnership still shapes the NYPL: the Library’s circulating collections are maintained by the city; its 4 research branches are privately funded, but open to all.

With money and vision secure, the Central Branch was built on the site of the Old Croton Reservoir. Before work could begin on Carrère & Hasting’s Beaux-Arts masterpiece, 500 workers spent two years preparing the site. Finally, the cornerstone was laid on November 10, 1902.

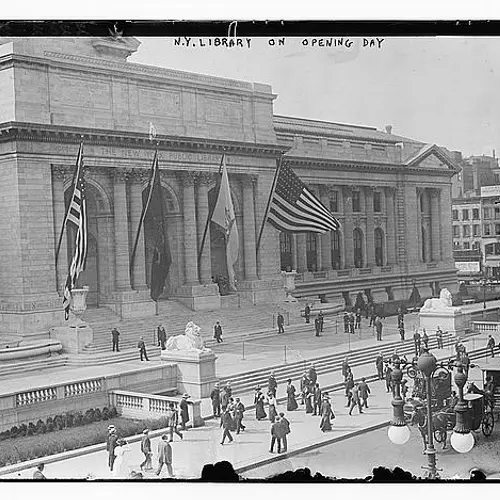

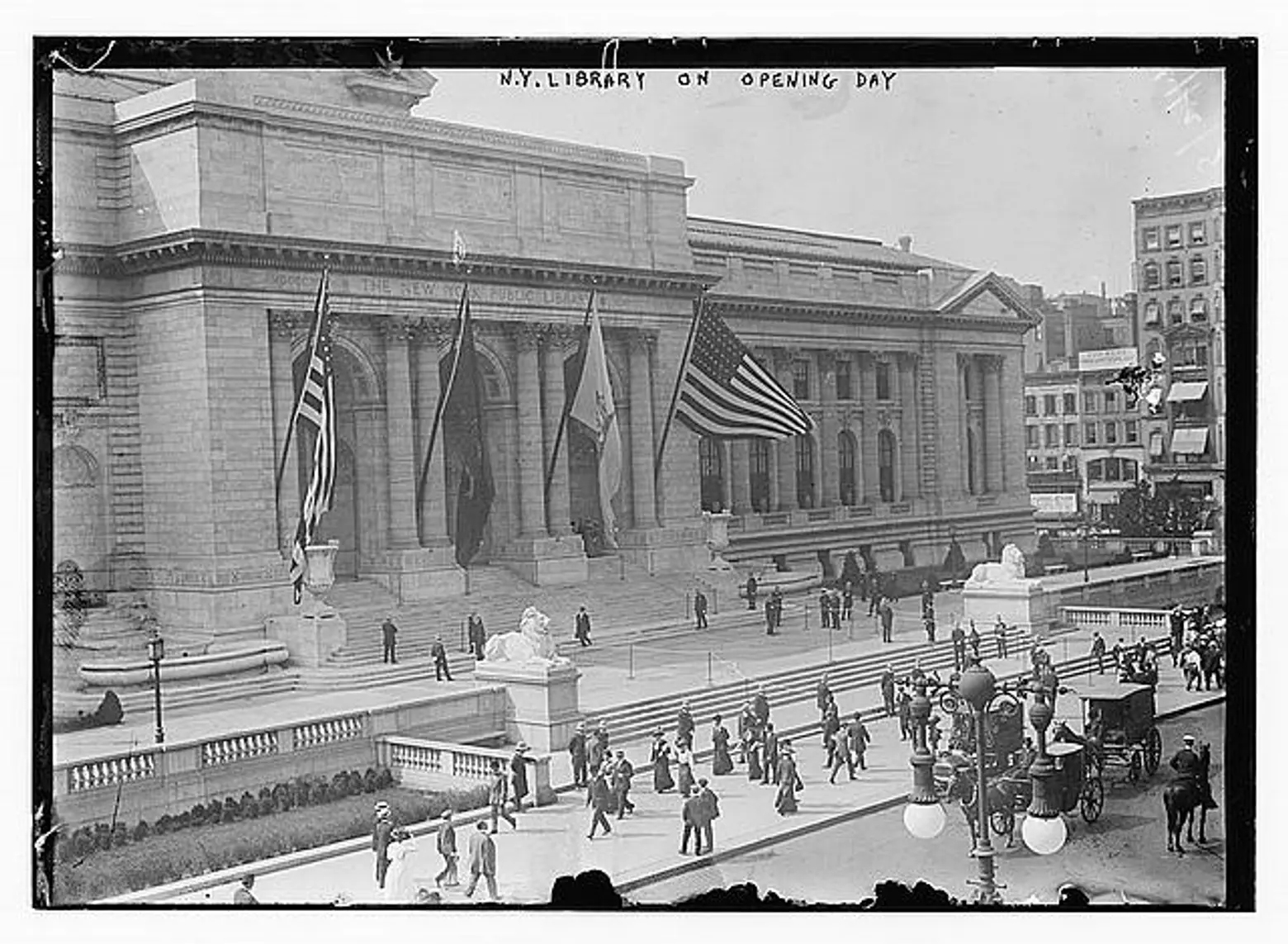

NYPL on opening day, via the Library of Congress

NYPL on opening day, via the Library of Congress

When the Library opened May 23, 1911, crowds of 50,000 marked the occasion. So impressive was New York’s “splendid temple of the mind,” President Taft called its opening a day of Nation importance, declaring that the Library would be a model for other cities hoping to spread knowledge among the people.

Vladimir Lenin agreed. He touted NYPL as a model because the system made its “gigantic, boundless libraries available, not to a guild of scholars, professors and other such specialists, but to the masses.” (Lenin himself enriched the Library – NYPL acquired a large measure of the private collections of the Czars when the Soviet Union sold its treasures after the Revolution.)

Lenin loved the Library, but in its first decades NYPL was decidedly all-American. It sent books overseas to soldiers during WWI, and in 1926, the Library staff boasted six former Olympic athletes: a hurdler, three high jumpers, one broad jumper, a mountain climber, an oarsman/canoeist, and a discus thrower.

The 1920s also proved a landmark decade for the Library because the Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints—the forerunner to today’s Schomburg Center—opened as a special collection at the 135th Street branch in 1925. The following year, the division garnered worldwide acclaim when it acquired Arturo Alfonso Schomburg’s personal collection of over 10,000 books, manuscripts, etchings, paintings and pamphlets.

By the 1930s, the Library, built for the people, was practically the Popular Front: radical librarians published their own in-house quarterly called Class Mark, declaring, “We are the librarians, pages, and service workers in the New York Public Library system who are members of the Communist Party and of the young Communist League.”

The lion sculptures by Edward Clark Potter were installed in 1911, ahead of the opening, via Wiki Commons

The lion sculptures by Edward Clark Potter were installed in 1911, ahead of the opening, via Wiki Commons

The Library may have seemed its most radically hopeful during the Depression, when use reached its record high. Mayor LaGuardia nicknamed the Library’s lions Patience and Fortitude, because he believed those qualities would get New Yorkers through the tough times. Between 1929 and 1939, the Central Building was open 365 days a year, 9am-10pm Monday-Saturday, and 1pm-10pm on Sunday. The City’s contract with the Carnegie branches required that they remain open 12 hours daily except Sundays. Writer and critic Alfred Kazin remembered the library crowds during those years: “That Depression crowd, so pent up, searching for puzzle contests, beauty contests, treasure of Sandy Hook…I could hear day and evening those relentless hungry footsteps.”

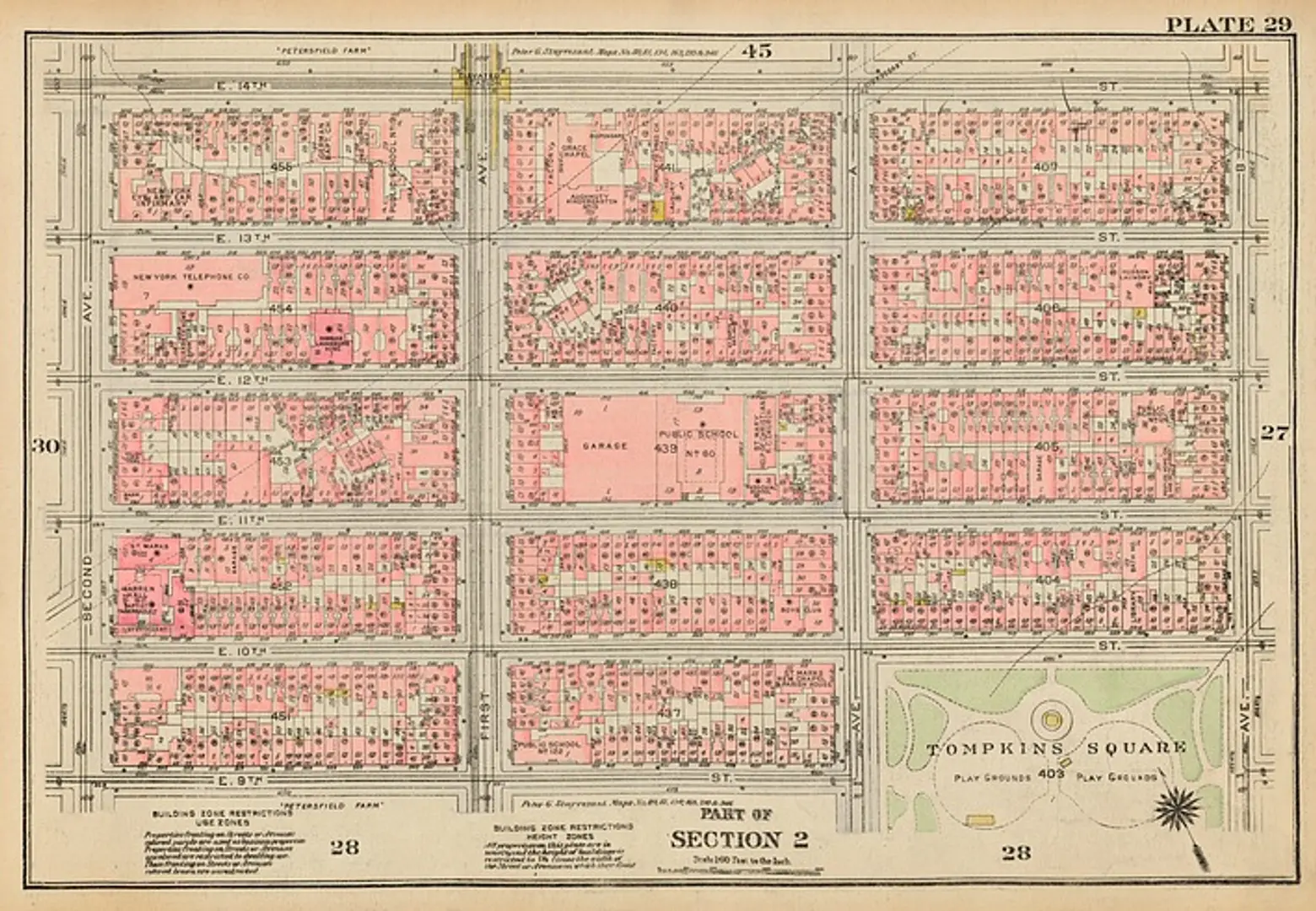

A fire insurance map of the East Village from 1927, via NYPL

A fire insurance map of the East Village from 1927, via NYPL

As the Depression gave way to WWII, the Maps Division followed suit. The Library’s maps of North Africa and of Normandy informed the Allies’ largest-scale invasions; on their most precise bombing missions, NYPL’s maps helped Allied pilots recognized their targets.

And as the “Atomic Age” dawned, industrial firms had fulltime researchers at work in the Library’s Economics, Science and Technology Divisions. When the nation awaited a decision in Brown v. Board of Education, interested parties could have appealed to the Library, because lawyers on both sides of the case used NYPL’s collection on state education laws to write their briefs.

In the 1960s and 70s, the collections changed and expand with the world itself. As empires fell and new nations were forged, the Library collected in every region and language. The nature of the collections changed, too. A Librarian working in the 1960s explained, “The Library started out being the best Arabic collection in the United States, and was especially strong in classical Arabic literature and Islam. Now there is a sharp rise, in countries from Morocco to Iraq, in materials dealing with economics politics and law, so the nature of our collections keeps changing.”

Other changes took place closer to home, and the Library was the eye of the storm. Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique in the Library, and claimed in the introduction to her landmark text, “I wouldn’t have even started it if The New York Public Library had not, at just the right time, opened the Frederick Lewis Allen Room.”

Amidst the ferment, the Library was in for a physical change. In 1965, the Performing Arts Collection, the largest of its kind in the world, got its own research branch at Lincoln Center. The Schomburg Center opened as its own research institution in 1972.

Rendering of the Mid-Manhattan Branch’s current renovation, courtesy of Mecanoo with Beyer Blinder Belle

Rendering of the Mid-Manhattan Branch’s current renovation, courtesy of Mecanoo with Beyer Blinder Belle

As the research divisions expanded, so did the Branch Libraries. Today there are 88 branch libraries, and each one has reinvented itself as many times as the New Yorkers it serves. For example, the Belmont Library, opened in 1980 at 186th Street and Arthur Avenue in the Bronx, was once Cinelli’s Savoy Theatre, better known as “The Dumps,” where cartoons were king, and women sat “shelling peas for that night’s supper.”

Rendering of the main branch’s new 40th Street entrance, courtesy of Mecanoo with Beyer Blinder Belle

Rendering of the main branch’s new 40th Street entrance, courtesy of Mecanoo with Beyer Blinder Belle

And today, its Mid-Manhattan branch at 5th Avenue and 40th Street will undergo a $200 million renovation by Dutch architecture firm Mecanoo. The Library is calling the project, a “state-of-the-art library that will serve as both a model and catalyst for a rejuvenated library system.” To that end, they also unveiled this past November a $317 million master plan for the iconic main branch. Also to be undertaken by Mecanoo with NYC-based Beyer Blinder Belle, the plan will add 20 percent more public space to the building and transform long-underutilized, historic spaces, along with many other improvements.

Photos of the renovated Rose Main Reading Room by Max Touhey Photography courtesy of the New York Public Library

Photos of the renovated Rose Main Reading Room by Max Touhey Photography courtesy of the New York Public Library

But one thing that doesn’t change is the glorious, landmarked Rose Main Reading Room at 5th Avenue and 42nd Street, which was refurbished in 2016. A sun-filled chamber two blocks long, Room 315 can seat up to 700 people, at “the heart of the heart of the library.”

Henry Miller handily summed up Rose’s thrill: “Working amidst so many other industrious students in a room the size of a cathedral, under a lofty ceiling which was an imitation of heaven itself…wondering what question I could put to the genius which presided over this vast institution which it could not answer. There was no subject under the sun which had not been written about and filed in those archives.”

Throughout NYPL’s history, Library staff has hunted down millions of answers. They run a wild gamut, from whether the city of Chemnitz was part of the kingdom of Saxony in 1899, to how long an asp bite would take to kill a human being, to queries regarding the specific heat of tooth enamel. Judges have called during trials, surgeons have called during operations, irate McDonald’s customers have called from the Drive Thru. (You can call too, at 917-ASK-NYPL.)

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

RELATED:

- NYPL unveils $317M master plan and renderings for iconic main branch

- NYPL’s historic Rose Main Reading Room is officially an interior landmark!

- New Yorker Spotlight: Behind the Reference Desk at the New York Public Library with Philip Sutton

- Is It Possible to Keep an Octopus in a Private Home? And Other Questions Posed to the New York Public Library

Via

Via