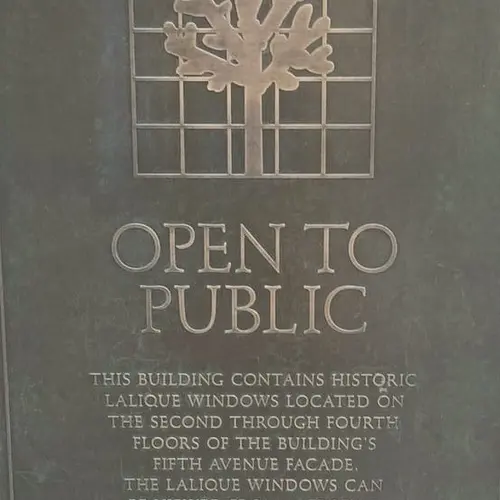

René Lalique’s windows saved this Fifth Avenue building from destruction in the 1980s

In 1984, a series of grime-covered windows at 714 Fifth Avenue caught the attention of an architectural historian by the name of Andrew Dolkart. Seemingly innocuous, and almost industrial in aesthetic—at least from afar—the glass panes would later become the foundation for a preservation victory.

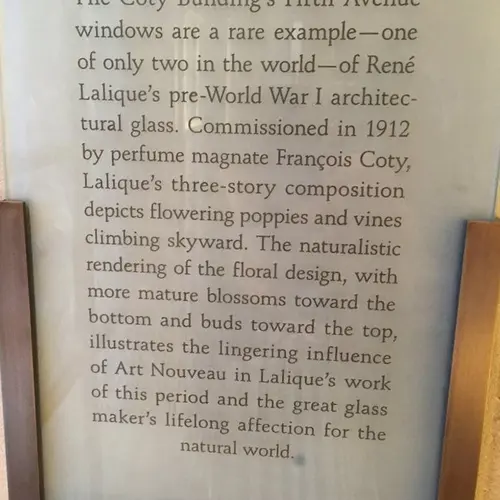

As the story goes, Dolkart, was out doing research for the Municipal Arts Society when he passed a commercial building that had been tagged for demolition to make way for a skyscraper. Despite being covered in dirt, Dolkart noticed that the windows were not ordinary windows, but rather exquisite Art Nouveau panels from renowned French glass artist René Lalique designed for perfumer François Coty in 1910. The discovery, as it turns out, was deemed important enough to save the limestone building from its fate as rubble.

François Coty, Perfumer

With genealogical roots tracing back to Napoleon, Joseph Marie François Spoturno was born in 1874 on the French island of Corsica. After years in the military, he moved to Paris and married Yvonne Alexandrine Le Baron. He also started using the name François along with assuming the last name Coty, a variation of his mother’s maiden name.

Coty’s introduction to perfumery began when he met a pharmacist named Raymond Goery who made and sold perfume. It was in Goery’s Paris shop where Coty experimented with scents and where he would eventually develop his first fragrance, “Cologne Coty.”

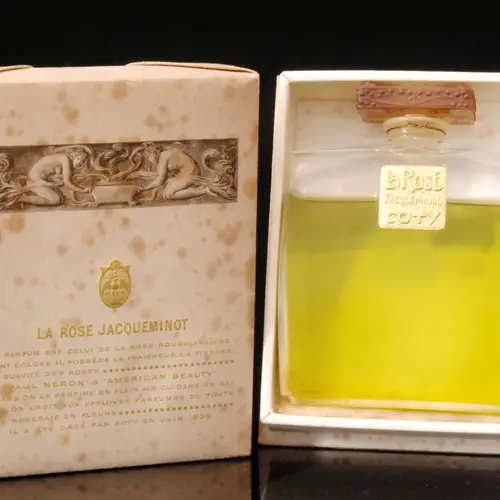

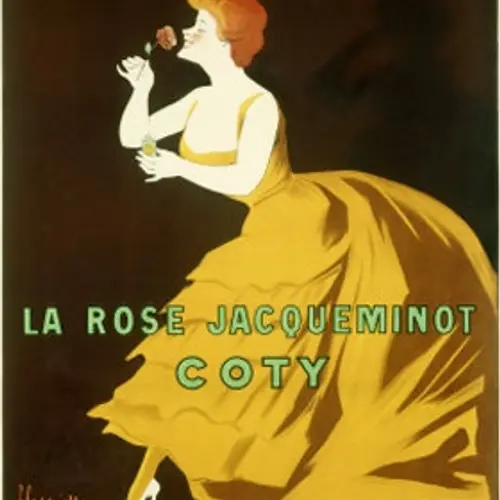

His life continued to change after his wife introduced him to a member of the Chiris family, longtime manufacturers and distributors of perfume. Coty studied perfumery at the Chiris’ factory in Grasses (southern France) and began to work on his second fragrance, which he called “La Rose Jacqueminot.”

When he returned to Paris in 1904, he had little success peddling his new fragrance. That is until he accidentally broke a bottle in a department store. As legend has it, in the minutes that followed the flub, Coty sold his entire inventory of perfume, and the store offered him an area to continue selling his products.

La Rose Jacqueminot became so popular that it made Coty a millionaire, and it established him as a significant perfumer. He would open his own shop in Paris later that year.

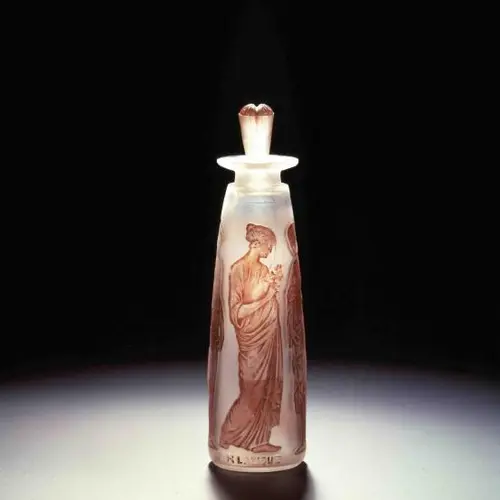

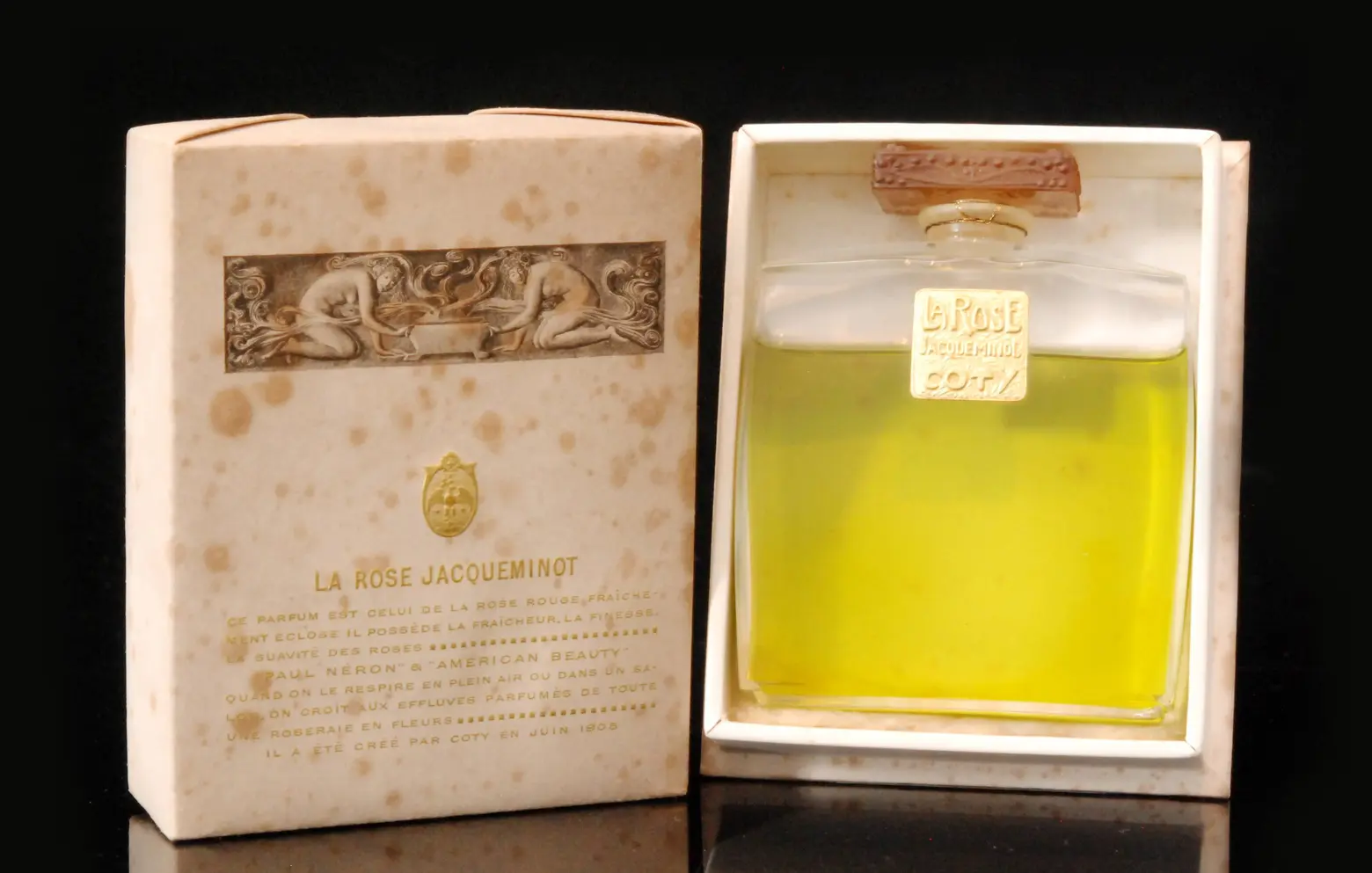

Coty, Vintage Baccarat bottle and box for La Rose Jacqueminot perfume, 1904. Photo, Fieldings Auctioneers

Coty, Vintage Baccarat bottle and box for La Rose Jacqueminot perfume, 1904. Photo, Fieldings Auctioneers

In addition to being a talented perfumer, Coty was also a genius at marketing. He recognized early on that an attractive bottle and packaging were essential to a perfume’s success. La Rose Jacqueminot was sold in a Baccarat bottle, but his most successful collaborations were with René Lalique, the French jeweler known for his Art Nouveau designs.

René Lalique, Artist

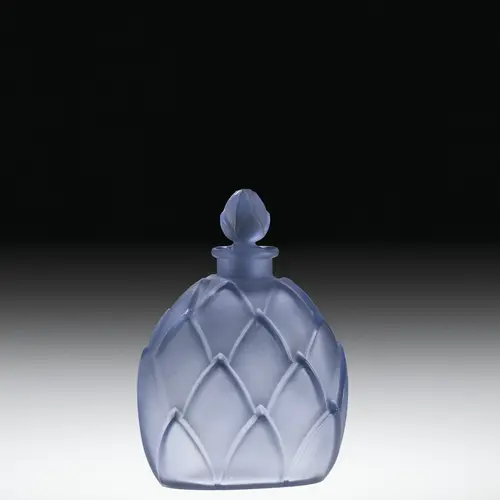

In 1905, René Lalique opened a shop in Paris where he exhibited his jewelry and glass objects. François Coty was so impressed by Lalique’s designs that he asked him to create glass bottles for Coty’s early scents, Ambre Antique and L’Origan, two pivotal products for the company. Lalique’s designs elevated the creation of the perfume bottle to an art form.

Over the years, Lalique would create 16 bottles for Coty. He would also go on to design countless other perfume bottles through the 1930s for other companies including Gabilla, Guerlain, Lucien Lelong, D’Orsay, Roger & Gallet, and Worth.

Glass perfume bottle designed by Lalique for Coty in 1920 (Photo: Corning Museum of Glass)

Glass perfume bottle designed by Lalique for Coty in 1920 (Photo: Corning Museum of Glass)

During Lalique’s prolific 60-year career, from 1885 until 1945, he evolved from master jeweler to architectural glass designer. He made necklaces, brooches, bracelets, hair combs, lamps, wine glasses, glass plaques, vases, hood ornaments for luxury vehicles, decanters, sculptures and architectural works like the windows of the Coty Building. His mastery was in the lost-wax process, and understanding how light reacted with glass, namely how it diffused light and transformed the color of the glass. In fact, most of Lalique’s designs were painstakingly etched by molding, hand engraving, or wheel cutting. Moreover, in 1925, when Lalique described his creative process to Maximilien Gauthier, a French art critic, he revealed that two of his primary sources of inspiration were women and nature—both of which can be seen in almost every piece of jewelry and glass he designed during his career.

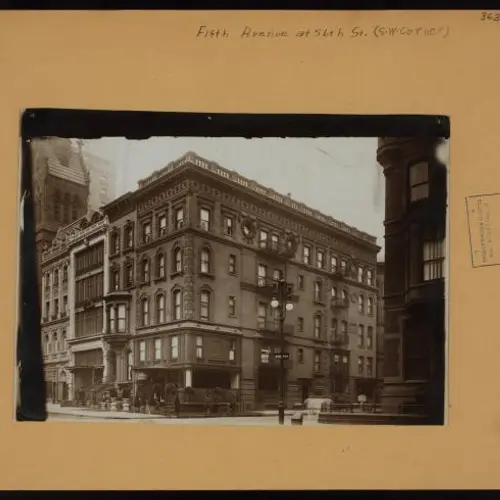

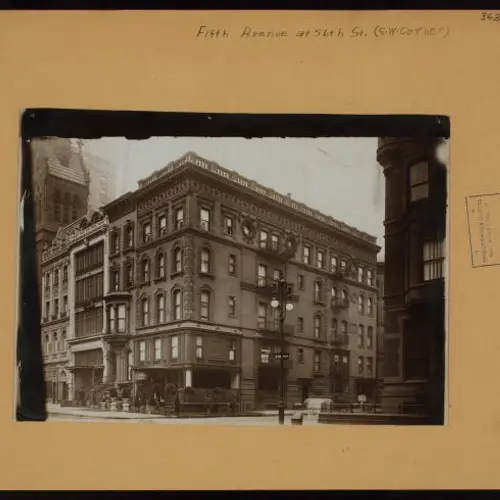

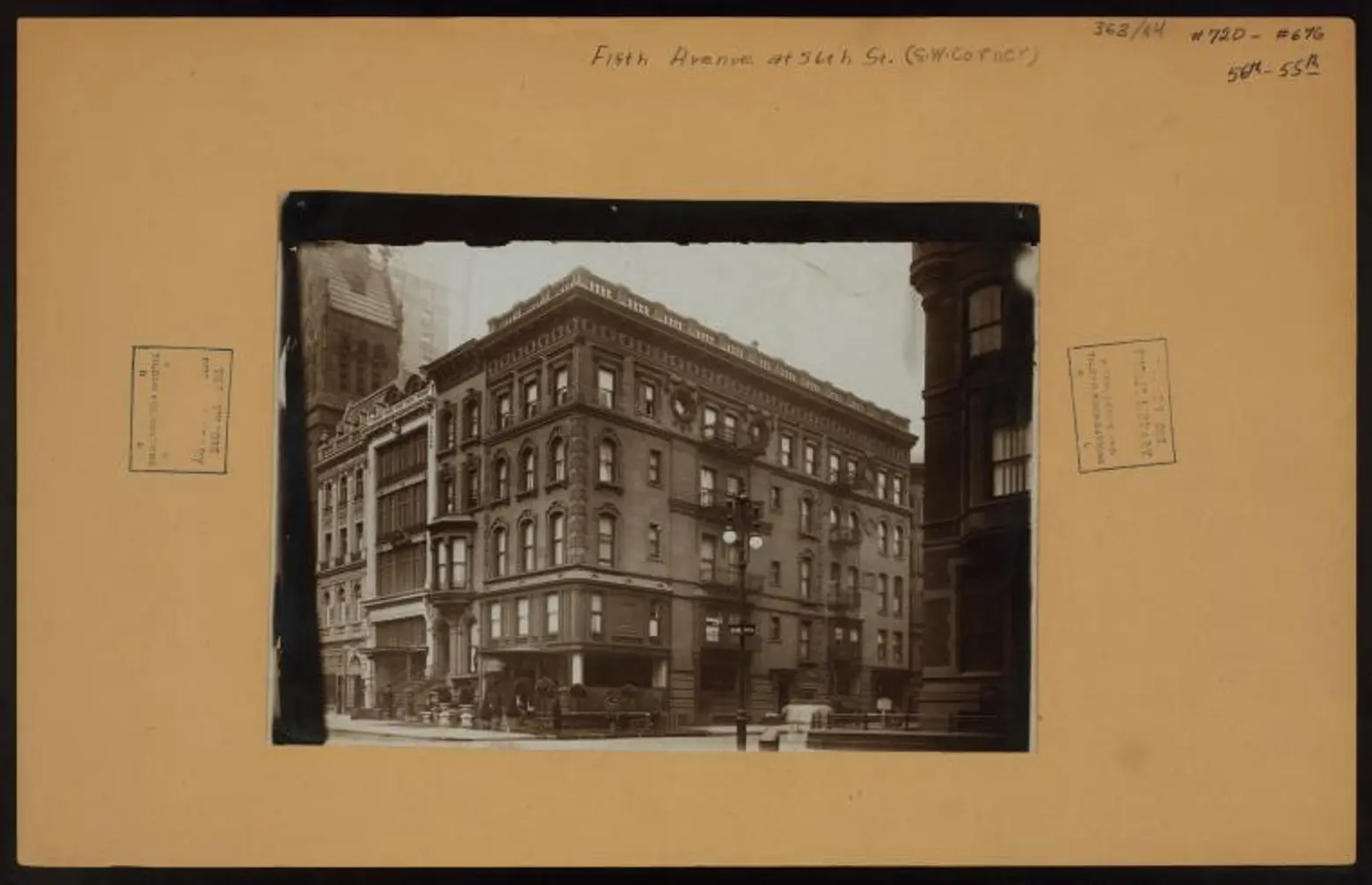

Image courtesy of the NYPL

Image courtesy of the NYPL

The Building

Originally built in 1871 as a row house, change first came for the Fifth Avenue building when the facade was altered in 1907. Charles Gould, the owner and a real estate investor, wanted his mansion on Millionaire’s Row converted into a six-story commercial building that would blend well with the elaborate mansions of the wealthy who still lived in the area.

The French-style structure assimilated beautifully into the environment, and the limestone facade mimicked the adjacent buildings. What made the building different, however, was the expression of the top three floors where walled glass was added to the frontage. Gould felt this was the best way to attract commercial tenants to his Fifth Avenue address.

Coty Building, currently occupied by Henri Bendel, 714 Fifth Avenue

Coty Building, currently occupied by Henri Bendel, 714 Fifth Avenue

As the facade alteration was being completed in 1908, Coty’s company was expanding in France with the success of La Rose Jacqueminot. Later that year the New York Times would report that Charles Gould’s residence had been leased to a French perfumery and alternations would be made accordingly; Coty had signed a 21-year lease for the building and immediately commissioned René Lalique to replace the wall of windows in 1910.

As the Daytonian so aptly describes, “The extraordinary three-story work of art, reminiscent of the Art Nouveau designs that made the artist [Lalique] world-renowned, consists of intertwining vines and flowers climbing up the side windows while leaving the central-most panes clear. The overall effect of the composition could be appreciated only from the street. The windows, while not original to the design of the building, instantly became its most striking feature.” Poppies are the flowers represented in the work.

Preservation

In 1983, developer David S. Solomon began assembling a development site to make way for a new 44-story skyscraper. His intent was to demolish the Coty Building and the adjacent Rizzoli Building (712 Fifth Avenue), as neither were designated as landmarks.

However, soon after the news broke, the Municipal Art Society petitioned the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate the building. And when the Lalique windows were brought to their attention, they agreed to schedule a hearing.

The building would ultimately earn its designation in 1985, but in an unexpected plot twist, the LPC also approved a Certificate of Appropriateness for the tower to be built behind the two existing buildings. As such, only the facades of the original buildings remain today, acting as a frame for the Lalique windows.

Lalique windows on Coty Building before restoration. Photo from LPC designation report, 1985

Lalique windows on Coty Building before restoration. Photo from LPC designation report, 1985

In 1986, all 276 of the 14”x 14” Lalique panels were removed from the facade and restored by the Greenland Studio of Manhattan. Unfortunately, 46 panels were deemed damaged beyond repair and had to be replicated by Jon Smiley Glass Studios of Philadelphia.

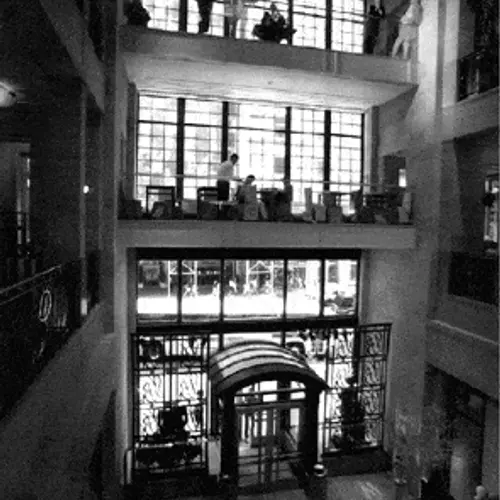

Beyer, Blinder, Architects would later restore the facade in 1990 during a renovation of the interior for the flagship store of Henri Bendel. A four-story atrium replaced the former Coty offices, and observation levels were added inside so that Rene Lalique’s windows could be viewed from various floors.

A decade later, the windows would have to undergo a second restoration to correct the framing system. Ten of the windows cracked because the steel frame expanded from water erosion which created pressure on the glass panes.

Rene Lalique window of Henri Bendel store looking out over Fifth Avenue, after restoration (2016)

Rene Lalique window of Henri Bendel store looking out over Fifth Avenue, after restoration (2016)

Today

Coty’s personal life would ultimately be his demise. Known for his philandering, he married Henirette Diede who was his mistress during his first marriage. His empire suffered following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and then Henriette divorced him to marry someone else. The divorce settlement granted her millions (of francs), paid in three installments. Coty defaulted on the last payment in 1931 stating financial hardship, and Henriette was thus awarded ownership of most of his companies and newspapers. Before agreeing to the new terms, she stipulated the no member of the Coty family would ever be involved in the company.

The company would eventually rebound and find rapid growth, fueled by U.S. soldiers bringing Coty products from abroad following WWI. In 1940, Coty moved its operations to the west side where both a factory and laboratory were constructed to accommodate increased production. And though Coty no longer occupied the Fifth Avenue structure, “The Coty Building” moniker stuck.

In 1963, Henriette sold the company to Pfizer who would later sell it to a German company.

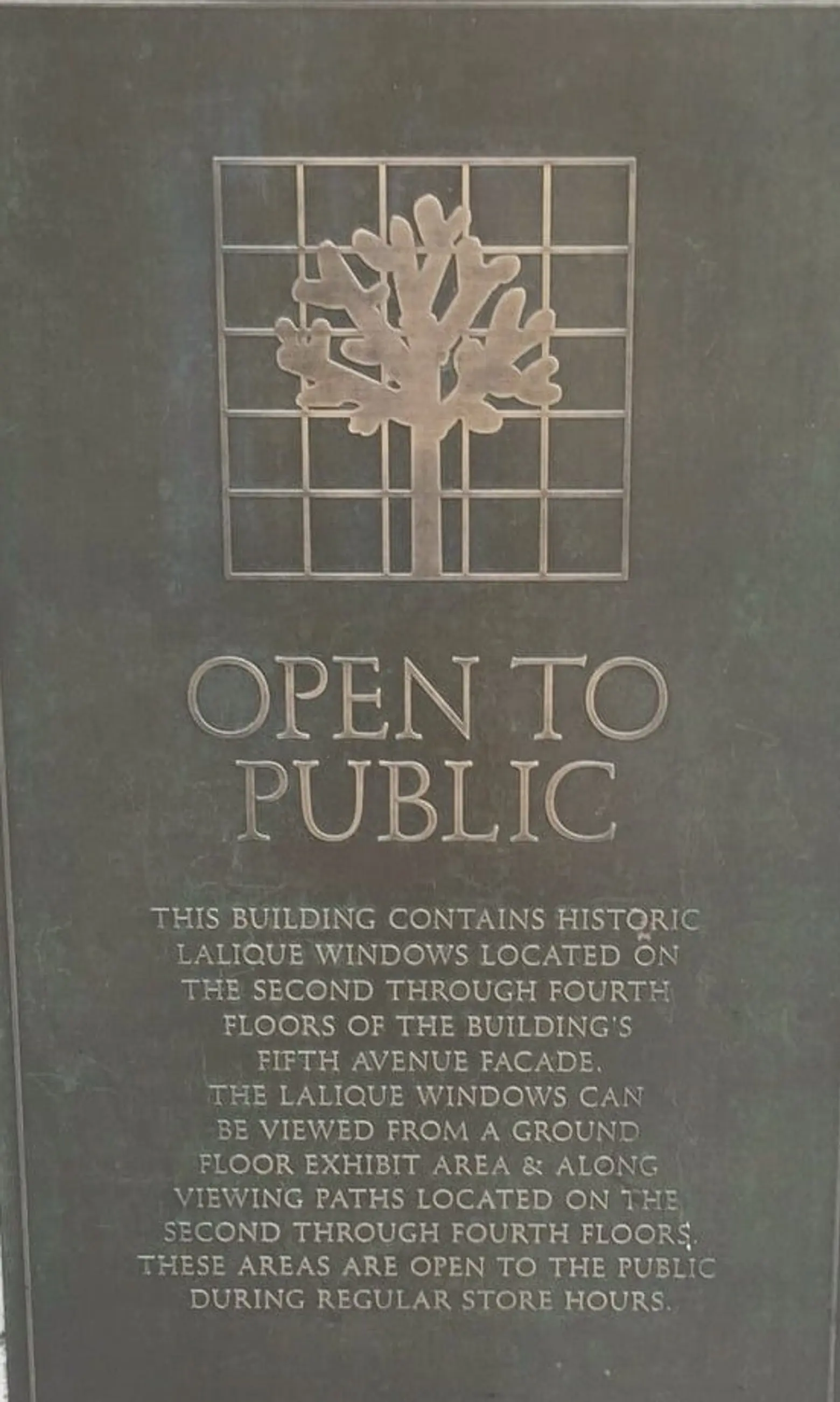

Exterior plaque of Henri Bendel 714 Fifth Avenue

Exterior plaque of Henri Bendel 714 Fifth Avenue

According to the New York Times, in 1988, developer David S. Solomon agreed in writing that the ”ground floor of the Fifth Avenue atrium at all times shall be restricted to unobstructed lobby use and may not be used for any retail sales activities.” There has been some discussion along the way about the retail encroachment of Henri Bendel into the atrium, but it’s balanced by the creation of a privately-owned space that is publicly accessible. This example of hybrid preservation continues to be a victory in retaining New York’s awesome history.

RELATED:

- LPC Approves Faux-classical mansion on notorious UES site of blown up townhouse

- POLL: Is Fifth Avenue Losing its luster amid soaring rents and empty storefronts?

- Exclusive Photos: Tour the lavish south wing of the Gilded Age Villard houses