Roasteries and refineries: The history of sugar and coffee in NYC

Arbuckle’s, via Brooklyn Historical Society

Brooklyn is properly known as Kings County. During New York’s Gilded Age, Sugar King Henry Osborne Havemeyer and Coffee King John Arbuckle made sure the borough lived up to its name, building their grand industrial empires on the shores of the East River. By the turn of the 20th century, more sugar was being refined in Williamsburg and more coffee roasted in DUMBO than anywhere else in the country, shaping the Brooklyn waterfront and NYC as a preeminent financial and cultural center. The history of coffee and sugar in this town is as rich and exciting as these two commodities are sweet and stimulating, so hang on to your homebrew and get ready for a New York Story.

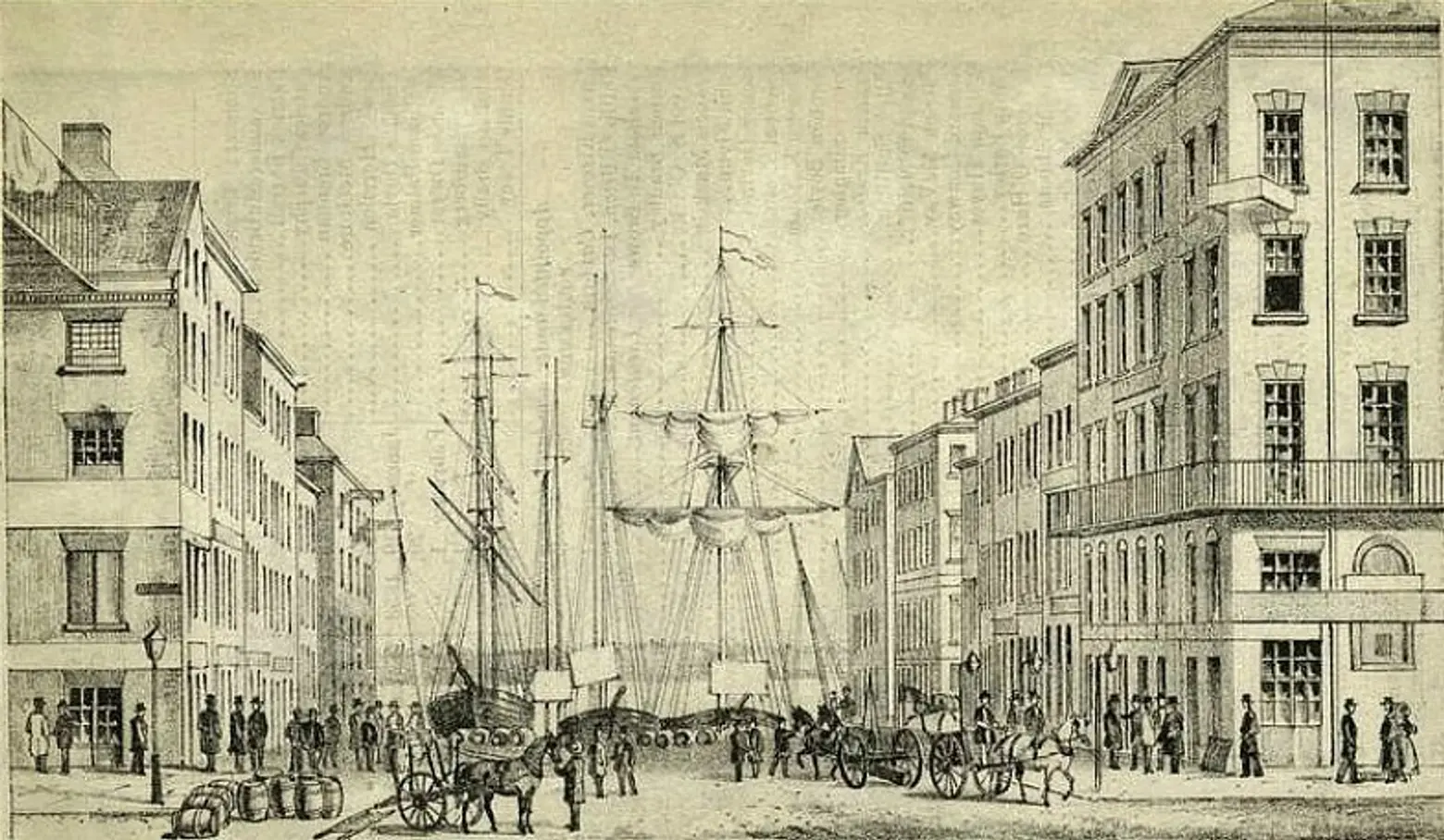

Merchants Coffeehouse on the left in 1856, via NYPL

Coffee has kept New York awake since at least 1668 when the first written reference to the drink in America noted that New Yorkers were sipping a beverage made of roasted beans that was flavored with sugar, or honey and cinnamon.

During the American Revolution, coffee became the drink of patriots. Following the Boston Tea Party, the die was cast: tea was for Tories, and coffee served as a revolutionary symbol and national addiction. Coffee was so important to the founding of the Republic, that the Merchants Coffeehouse on Wall and Water Streets was known as the “Birthplace of the Union,” and was the site where the Governor of New York State and Mayor of New York City greeted George Washington when he arrived in Manhattan as President-elect on April 28th, 1789.

The Livingston Sugar House via Wiki Commons

New York’s Sugar Refineries played a more notorious role in the Nation’s founding – as prisons. In November 1852, the New York Times published Levi Hanford’s harrowing account of his internment during the Revolution in British-occupied New York City as a POW in the Old Livingston Sugar House on Liberty Street.

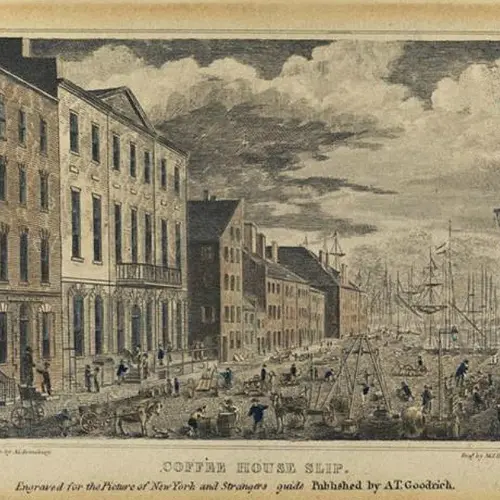

By the 19th century, New York had cornered the market on coffee. The “coffee district” thrived on Lower Wall Street. Its heart was on Front Street, but it also extended to South and Pearl Streets. In fact, in the South Street Seaport, there was even a Coffeehouse Slip where importers known as “coffee men” presided over the bustling trade.

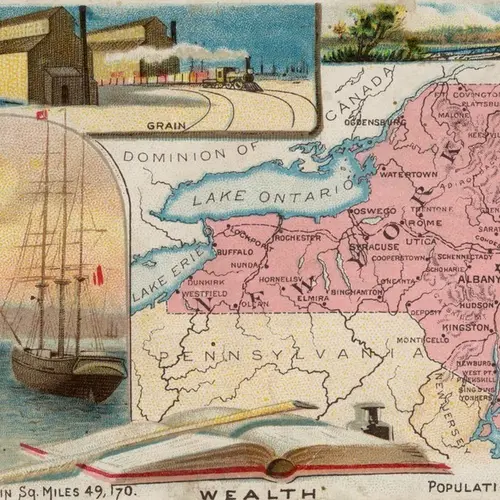

The bitter brew, and sugar to sweeten it, were flowing full tilt through Manhattan because New York boasts the finest natural harbor in North America. This city’s natural primacy in shipping made it a center of extraordinary industry, and the perfect nexus for a trade in global commodities.

While sugar and coffee may have been roasted and refined on the shores of the East River, the beans and cane from whence those products came were grown much further afield. The raw sugar that docked in first in Manhattan, then later in Brooklyn, came chiefly from the Caribbean, and the green coffee from South America and South East Asia, where they were initially grown by slaves. Accordingly, coffee and sugar were both part of a system of global capitalism, colonialism and slave labor.

A 1797 painting by Francis Guy. The building with the American flag on its roof is the Tontine Coffee House. On the far right is the Merchant’s Coffee House, where the stockbrokers of the Buttonwood Agreement and others did trade before the construction of the Tontine. On the right is Wall Street, leading down to the East River. Via Wiki Commons.

A 1797 painting by Francis Guy. The building with the American flag on its roof is the Tontine Coffee House. On the far right is the Merchant’s Coffee House, where the stockbrokers of the Buttonwood Agreement and others did trade before the construction of the Tontine. On the right is Wall Street, leading down to the East River. Via Wiki Commons.

Coffee and sugar are so intimately tied to New York’s rise as the world’s preeminent financial center, that the first New York Stock Exchange was held in The Tontine Coffee House on Wall and Water Streets. An early 19th century visitor from England described the rollicking scene:

The Tontine coffee-house was filled with underwriters, brokers, merchants, traders and politicians; selling, purchasing, trafficking, or insuring; some reading, others eagerly inquiring the news. The steps and balcony of the coffee-house were crowded with people bidding or listening to several auctioneers, who had elevated themselves upon a hogshead of sugar, a puncheon of rum or a bale of cotton; with Stentorian voices were exclaiming “Once. Twice.” “Once. Twice.” “Thank ye, gentlemen.” Or were knocking down the goods which took up one side of the street to the best purchaser. The coffee-house slip, and the corners of Wall and Pearl-streets, were jammed up with carts, drays and wheelbarrows; horses and men were huddled promiscuously together, leaving little or no room for passengers to pass.

Soon, coffee and sugar flowed from Front Street to the frontier. Coffee emerged at the cowboys’ preferred caffeine fix and a symbol of the rugged individualism of the American West. It was said in the middle of the 19th century that if a frontiersmen had coffee and tobacco, “he will endure any privation, suffer any hardship, but let him be without these two necessities of the woods, and he becomes irresolute and murmuring.” The drink was so popular that by the end of the 19th century, the United States consumed half the world’s coffee.

As coffee and sugar rolled west, New York’s roasteries and refineries headed east, to Brooklyn. New technology made it possible to produce previously unimaginable quantities of coffee and sugar, but these new vacuum pans, filters, and kilns required more space than the tip of Manhattan could provide. Thankfully, the Brooklyn waterfront had it all: deep water, available labor, and space to build.

After the Civil War, the East River shoreline, in what is now DUMBO, was built up into a fortress of warehouses known as “stores” that housed a vast array of newly arrived commodities unloaded from ships in the harbor. These industrial behemoths were known as Brooklyn’s “walled city.” They housed products including cotton, lemons, jute, tobacco and coffee, and contributed to Brooklyn’s reputation as “America’s biggest grocery and hardware store.” In 1870, the historian Henry R. Stiles published the 3rd volume of his history of Brooklyn, and noted that the waterfront “is completely occupied by ferries, piers, slips, boat and ship-yards; with an aggregate amount of business which forms an important item of the commerce of the state.” In the years that followed, Sugar and Coffee dominated that business.

Henry Osborne Havemeyer, Sugar King and died-in-the-wool Robber Baron, presided over the Sugar Trust. One anti-trust prosecutor fabulously referred to Havemeyer’s empire as “a conscienceless octopus reaching from coast to coast,” but he could also have been talking about the man himself. Havemeyer was so proud of his unsentimental, cut-throat business acumen that he claimed to have no friends below 42nd street, meaning that nobody in the Financial District – and certainly nobody in Brooklyn – considered him a pal.

Between 1887 and 1891, he transformed what had been the Havemeyer and Elder Refinery between South 2nd and South 5th Street in Williamsburg into the American Sugar Refining Company, the then largest in the world. The outfit produced Domino Sugar, a symbol of the Williamsburg waterfront for generations, and the jewel in the crown of the Sugar Trust, turning out five million pounds of sugar per day. Other refineries could not compete with such extraordinary capacity and fell under the control of the Trust. By 1907, the Trust controlled 98 percent of the sugar refining capacity of the United States.

Havemeyer’s counterpart in coffee was John Arbuckle. By the turn of the 20th century, 676,000,000 pounds of coffee, or 86 percent of the total consumed in the United States, docked in New York Harbor. Arbuckle imported more than double the beans of the next largest New York importer, and presided over the scene as the “honored dean of the American coffee trade.”

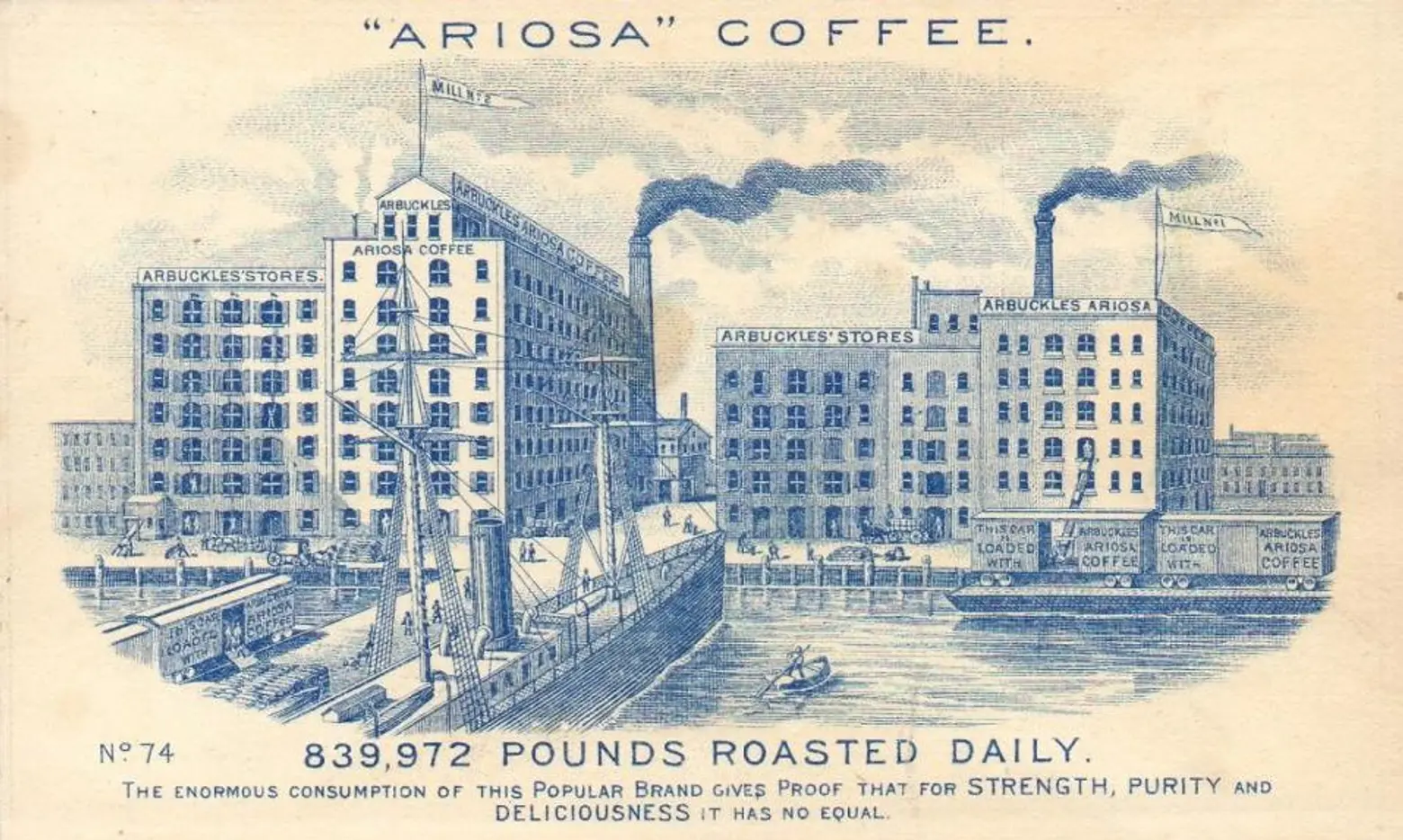

1880s advertisement for Ariosa coffee showing Arbuckle’s Brooklyn coffee plants, via New York History Walks

1880s advertisement for Ariosa coffee showing Arbuckle’s Brooklyn coffee plants, via New York History Walks

Arbuckle, who sported a beard that would make current Brooklynites jealous, was an inventor and visionary who transformed the way Americans consumed coffee. Before Arbuckle, most Americans bought their coffee green and roasted it themselves. Arbuckle thought he could deliver a better product if he roasted and packaged coffee for sale. He introduced Arosia Coffee in one-pound bags in 1873. Soon, Arosia accounted for between 1/5 and ¼ of all coffee sold in the Untied States.

Arbuckle was so passionate about the perfect cup, he invented his own roasters for use at his Brooklyn plant. To make sure his product was up to snuff, the Coffee King had a hand in every aspect of his business. He established coffee-exporting offices throughout Brazil and Mexico. He owned the shipping fleet that carried his beans to Brooklyn. He employed people from fields as diverse as blacksmithing and engineering, with doctors to take care of his workers and laundresses to wash his linen coffee sacks for reuse. He owned the printers that turned out labels for his packages and the trucks that carried them across the country. Arbuckle’s shipping barrels were made in an Arbuckle-owned barrel factory, from Arbuckle-owned timber. He even built his own railroad track throughout DUMBO’s industrial district to more easily move his product.

Rendering of the under-construction Domino Sugar Factory development via Mir

Rendering of the Empire Stores in DUMBO, via Midtown Equities

Rendering of the Empire Stores in DUMBO, via Midtown Equities

Today, Brooklyn’s industrial past is being repurposed. The Empire Stores that housed Arbuckle’s coffee are now home to co-working, gallery and museum space. The Domino Sugar Factory will be residential. The waterfront has changed, but coffee is back in Brooklyn. As specialty roasters continue the search for the perfect brew, they fit into a rich blend of the borough’s history.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

RELATED:

Get Inspired by NYC.

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

My grandfather Martin Kull worked at National Refining Company and I have his badge number Employee Number is A281. Is there any interest in having this badge displayed in the museum?

Thank you.

Joan Dale