Ruffle Bar and Robbins Reef: NYC’s Forgotten Oyster Islands

Ruffle Bar via Frogma

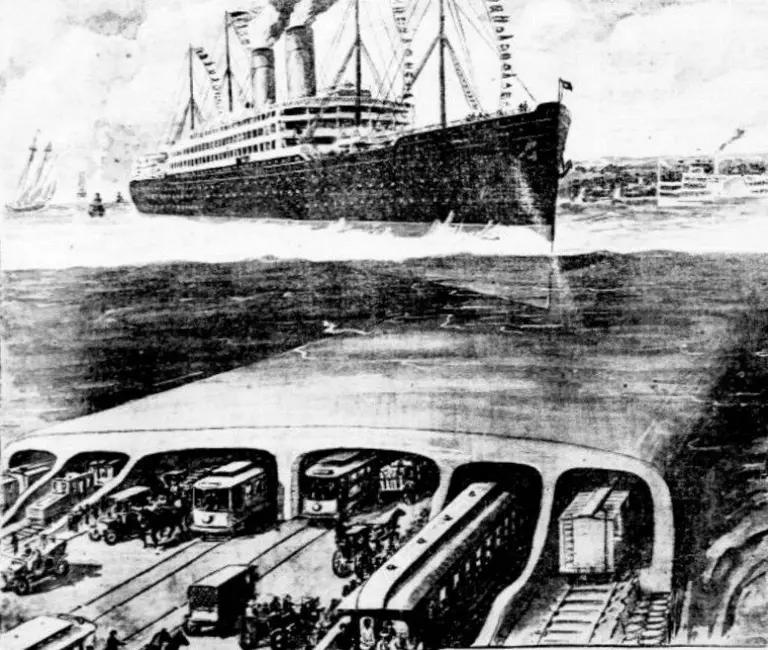

Today, when most New Yorkers think of oysters it has to do with the latest happy hour offering the underwater delicacies for $1, but back in the 19th century oysters were big business in New York City, as residents ate about a million a year. In fact, oyster reefs once covered more than 220,000 acres of the Hudson River estuary and it was estimated that the New York Harbor was home to half of the world’s oysters. Not only were they tasty treats, but they filtered water and provided shelter for other marine species. They were sold from street carts as well as restaurants, and even the poorest New Yorkers enjoyed them regularly.

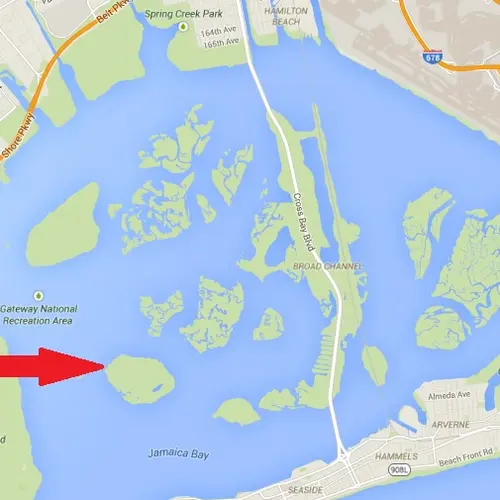

Though we know the shores of Manhattan, especially along today’s Meatpacking District and in the Financial District near aptly named Pearl Street, were chock full of oysters, there were also a couple of islands that played a part in New York’s oyster culture, namely Ruffle Bar, a sandbar in Jamaica Bay, and Robbins Reef, a reef off Staten Island marked with a lighthouse.

The 143-acre Ruffle Bar sits in the water just east of Floyd Bennett Field, bordering Brooklyn and Queens. Up until 1915, at which time the Department of Health determined that Jamaica Bay was too polluted to breed shellfish, Ruffle Bar was the center of the oyster and clam industry. As a 1941 New Yorker article recounts, “Up to that time, Jamaica Bay clams had been considered as tops by many connoisseurs. They often sold for as much as nine dollars a barrel. Their values brought about bootleg trade. Boatloads of Chesapeake Bay clams worth a dollar a barrel were dumped into Jamaica Bay at night and then pulled out the next morning, netting a clear profit of eight dollars.” At its height, Ruffle Bar was home to a community of oyster and clam fishermen, but the last known resident moved out in 1944.

Today, Ruffle Bar, like so many of New York City’s obscure or defunct islands, is a bird sanctuary. According to a young man who did a “Survivor”-style stint there in 2007, the land is still full of “delectables” like birds’ eggs, huge beds of mussels, and edible seaweed. However, there’s also a good amount of trash that’s washed up on the shores.

Robbins Reef is located in the Kill van Kull tidal strait between Staten Island and Bayonne, connecting Newark Bay with the Upper New York Bay. Unlike Ruffle Bar, which itself was sprinkled with oysters, Robbins Reef has hardly any land, other than that which occupies its famous “spark plug” style lighthouse (you’ve likely seen it if you’ve ridden the Staten Island Ferry). But it was part of one of the world’s largest oyster beds, making its lighthouse integral to the city’s oyster business, as well as to the shipping industry that came to the Staten Island and New Jersey ports. The name Robbins comes from the Dutch name for the small sandbar, Robyn’s Rift, which translates to seal reef, as groups of the marine mammals would lie on the sand during low tide.

Robbins Reef via Will Sherman for Cityphile

In addition to its location in the center of prime oyster territory, Robbins Reef is known for its longtime light keeper Katherine Walker. The 46-foot-tall lighthouse was built in 1883, replacing a granite tower that was erected in 1839. Katherine had moved to Sandy Hook, New Jersey in 1855 with her son after her husband passed away. She remarried to John Walker, the assistant keeper of the Sandy Hook Lighthouse. As Forgotten New York recounts, “In 1883 John Walker was reassigned to the newly reconstructed Robbins Reef Lighthouse, and lived with Kate at the lighthouse with Jacob and their daughter Mamie. Kate became the assistant lighthouse keeper and adjusted to an isolated life in the harbor. In 1886, the year the Statue of Liberty was dedicated, John came down with pneumonia and died, but not before charging Kate with the lighthouse’s upkeep: ‘Mind the light, Kate.'” The harbormaster named her the official lighthouse keeper in 1894, a position she kept until 1919. During that time, she would row her children to school on Staten Island, and she was credited with 50 rescues. In 1996, a Coast Guard vessel, “the premier maritime command & control platform in the tri-state region,” was named the USCGC Katherine Walker.

Similar to those oysters found around Ruffle Bar, the Robbins Reef oysters eventually succumbed to raw sewage pollution. The U.S. Coast Guard owned and operated the light house until the 2000s, and in 2011 the Noble Maritime Collection, a maritime museum on Staten Island, took control. You can take a virtual tour of the lighthouse today here.

According to an article on oyster history from the NYPL, “New York’s oysters were too polluted to eat by 1927, and pollution only increased in subsequent years. It was not until after 1972’s Clean Water Act that any improvements were seen, but the oysters are still not edible almost 40 years after the passage of that act. Dredging stirs up centuries worth of pollution lying thickly upon the harbor floor.” The lack of oyster ecosystems has left our estuary less able to clean its water and absorb excess nitrogen, and the loss of reefs has destabilized the sea floor and left the shoreline more susceptible to wave destruction.

A group of school children participating in the Billion Oyster Project program on Governor’s Island

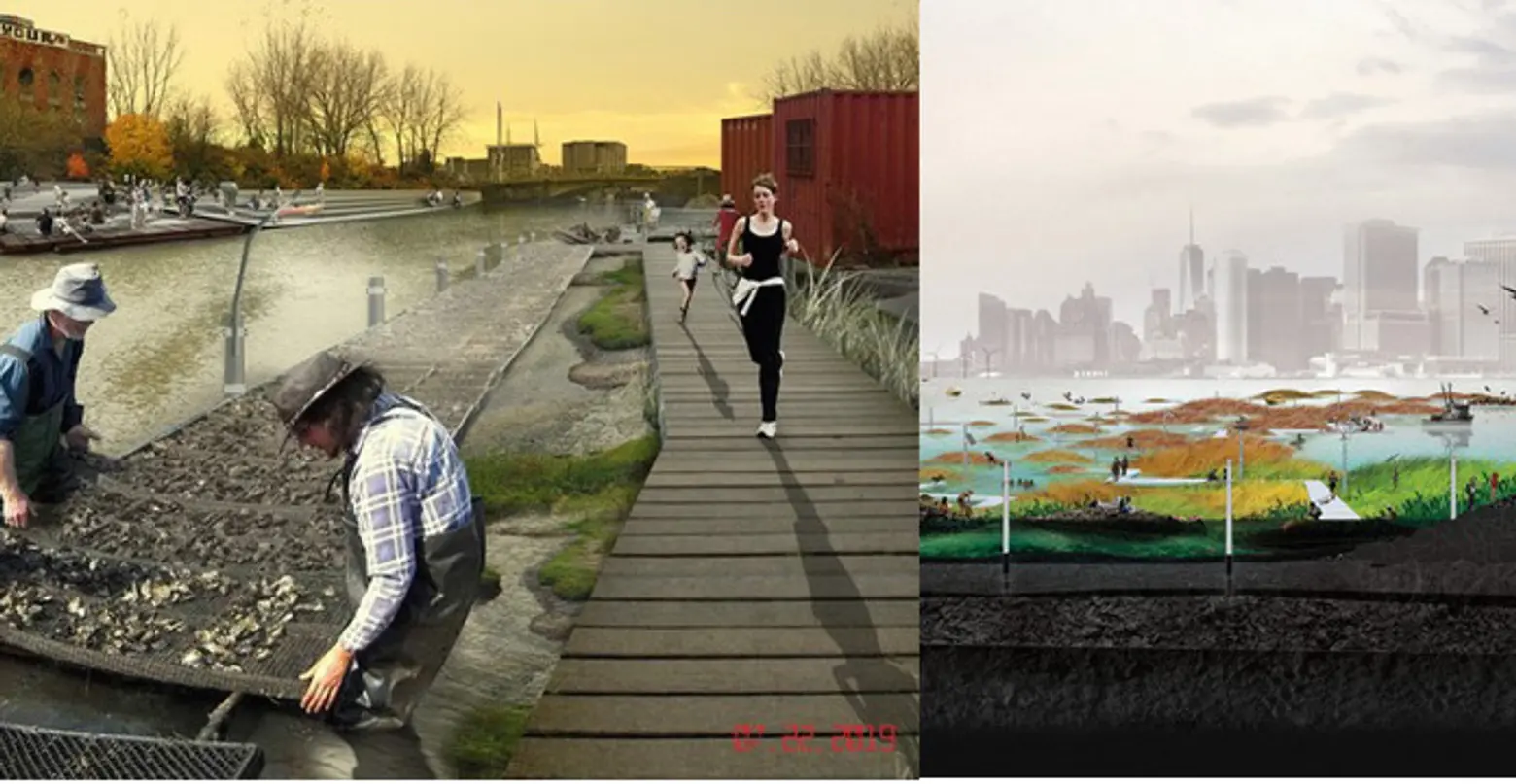

In recent years, there’s been a resurgence in oyster culture in New York City, with various groups looking at ways to bring the reefs back to our shores. The Billion Oyster Project is “a long-term, large-scale plan to restore one billion live oysters to New York Harbor over the next twenty years and in the process educate thousands of young people in New York City about the ecology and economy of their local marine environment.” To date, the group has grown 11.5 million oyster in the New York harbor and restored 1.05 acres of reef.

Image courtesy of SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE PLLC

In 2010, MoMA hosted an exhibition called Rising Currents, which brought together five interdisciplinary teams “to re-envision the coastlines of New York and New Jersey around New York Harbor and to imagine new ways to occupy the harbor itself with adaptive ‘soft’ infrastructures that are sympathetic to the needs of a sound ecology.” One of the five proposals came from Kate Orff and her landscape architecture and urban design firm SCAPE Studio. Orff developed the concept of oyster-tecture, “with the idea of an oyster hatchery/eco-park in the Gowanus interior that would eventually generate a wave-attenuating reef in the Gowanus Bay,” as we noted in an in-depth look at the firm’s work with oysters. They’re now working on the Living Breakwaters project with the goal of rebuilding of oyster habitats at strategic locations along the South Shore of Staten Island for wave attenuation. With the project moving ahead, perhaps some Robbins Reef oysters will pop up on the menu at our next oyster happy hour.

RELATED: