10 secrets of the Brooklyn Bridge

On May 24, 1883, throngs of New Yorkers came to the Manhattan and Brooklyn waterfronts to celebrate the opening of what was then known as the New York and Brooklyn Bridge. It was reported that 1,800 vehicles and 150,300 people total crossed what was then the only land passage between Brooklyn and Manhattan. The bridge–later dubbed the Brooklyn Bridge, a name that stuck–went on to become one of the most iconic landmarks in New York. There’s been plenty of history, and secrets, along the way. Lesser-known facts about the bridge include everything from hidden wine cellars to a parade of 21 elephants crossing in 1884.

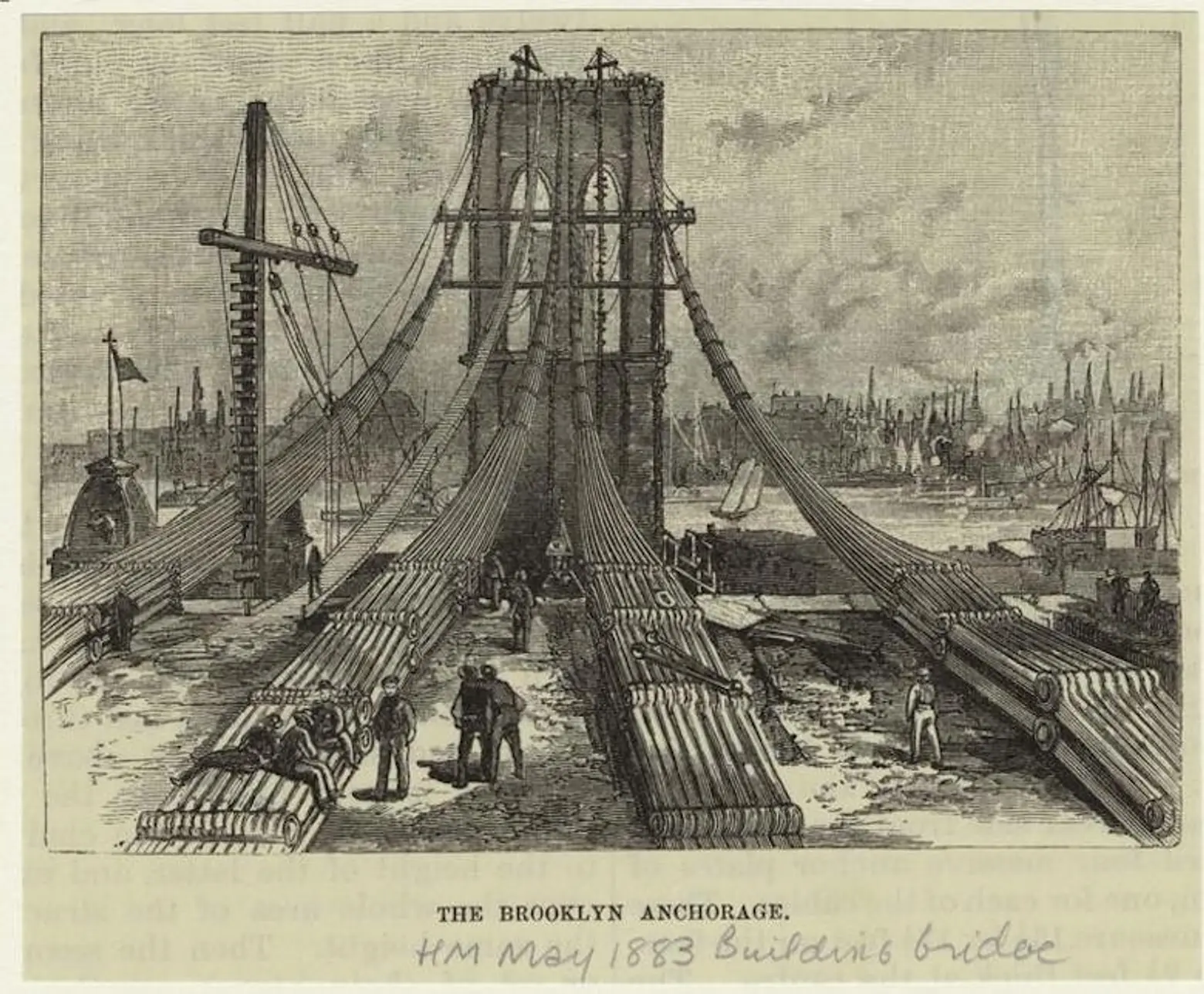

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “The Brooklyn anchorage.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1883-05.

1. The idea for a Brooklyn/Manhattan bridge was as old as the century

Much like the Second Avenue Subway, the idea of a bridge connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn was considered years before construction actually happened. According to The Great Bridge, by David McCullough, the first serious proposal for a bridge was recorded in Brooklyn in 1800. The carpenter and landscaper Thomas Pope proposed a “Flying Pendant Lever Bridge” to cross the East River, and his idea was kept alive for 60 years as plans for the Brooklyn Bridge developed. But the cantilevered bridge, made completely out of wood, didn’t prove to be structurally sound.

Chain bridges, wire bridges, even a bridge 100 feet wide were all proposed to connect the two waterfronts. The main challenge was that the East River, actually a tidal straight, is a turbulent waterway crammed with boats. The bridge needed to pass over the masts of ships, and could not have piers or a drawbridge.

2. When construction actually did start, the bridge was considered “symbolic of a new age”

When plans for a bridge came together, in the 1860s, planners, engineers, and architects knew this was not to be a run-of-the-mill bridge. From the offset, it was considered, according to McCullough, “one of history’s great connecting works, symbolic of a new age.” They wanted their bridge to stand up against projects like the Suez Canal and the transcontinental railroad. It was planned as the largest suspension bridge in the world, lined with towers that would dwarf everything else in view. At the time, steel was considered “the metal of the future” and the bridge would be the first in the country to utilize it. And once open, it would serve as a “great avenue” between both cities. John Augustus Roebling, the bridge’s designer, claimed it “will not only be the greatest bridge in existence, but it will be the greatest engineering work of the continent, and of the age.”

The bridge under construction; George Bradford Brainerd (American, 1845-1887). Construction of Brooklyn Bridge, ca. 1872-1887. Prints, Drawings and Photographs. Brooklyn Museum/Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection via Wikimedia

3. The towers were crucial to the bridge’s success

Many of the bridge’s construction challenges, which delayed the project for so many years, were solved by its identical 262-foot-tall towers. Architecturally, they were distinguished by twin Gothic arches–two in each tower–which allowed the roadways to pass through. Reaching more than 100 feet high, the arches were meant to be reminiscent of a church’s great cathedral windows. They were constructed of limestone, granite, and Rosendale cement.

Heralded as one of the most massive things ever built on the entire North American continent, the towers also served a crucial engineering role. They bore the weight of four enormous cables and held the cables and roadway of the bridge high enough so as not to interfere with river traffic.

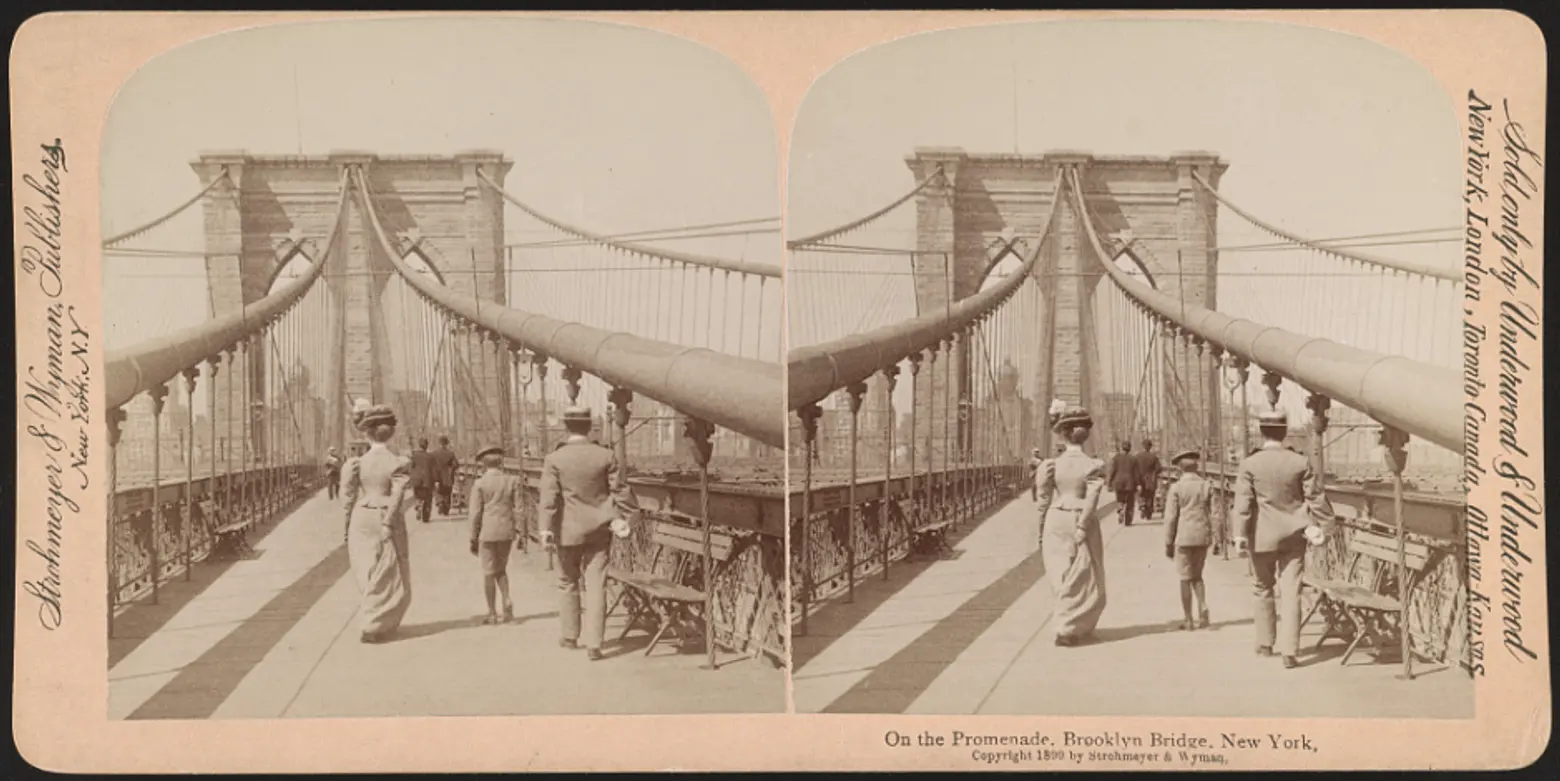

Strohmeyer & Wyman. On the promenade, Brooklyn Bridge, New York. New York, N.Y.: Strohmeyer & Wyman, Publishers. Photograph. The Library of Congress, Digital Collections

4. The first woman to cross the bridge also supervised its construction

John Roebling, the initial designer of the bridge, never got to see it to fruition. While taking compass readings in preparation for its construction his foot got stuck and crushed between a ferry and the dock. Doctors amputated his toes but Roebling slipped into a coma and died of tetanus. His son Washington Roebling took over responsibilities but suffered two attacks of caisson disease–known then as “the bends”–during construction. (A common ailment for bridge workers, the bends was caused by coming up too quickly in the compressed air chambers used to lay the foundations underwater.)

Washington Roebling, suffering from paralysis, deafness, and partial blindness, turned the responsibilities over to his wife, Emily Warren Roebling. Emily took on the challenge and studied mathematics, the calculations of catenary curves, the strengths of materials, and the intricacies of cable construction. She spent the next 11 years assisting her husband and supervising the bridge’s construction–many were under the impression she was the real designer. She was the first person to cross the bridge fully when it was completed, “her long skirt billowing in the wind as she showed [the crowd] details of the construction.” After that, she went on to help design the family mansion in New Jersey, studied law, organized relief for returning troops from the Spanish-American War, and even took tea with Queen Victoria.

5. The bridge was built with numerous passageways and compartments in its anchorages, including wine cellars

New York City rented out the large vaults under the bridge’s Manhattan and Brooklyn anchorages to fund the bridge. Some space in each anchorage was dedicated to wine and champagne storage, and the alcohol was kept in stable temperatures throughout the year. The cellar on the Manhattan side was known as the “Blue Grotto” and was covered in beautiful frescoes depicting vineyards in Germany, Italy, Spain, and France. They ended up closing in the 1930s, but a visit in 1978 uncovered this faded inscription: “Who loveth not wine, women and song, he remaineth a fool his whole life long.”

6. There’s also a Cold War-era bomb shelter under the bridge’s main entrance

As 6sqft pointed out a few years back, there is a nuclear bunker inside one of the massive stone arches below the bridge’s main entrance on the Manhattan side. It is full of supplies, including medication like Dextran (used to treat shock), water drums, paper blankets, and 352,000 calorie-packed crackers. The forgotten vault wasn’t discovered until 2006 when city workers performed a routine structural inspection and found cardboard boxes of supplies ink-stamped with two significant years in Cold War history: 1957, when the Soviets launched the Sputnik satellite, and 1962, during the Cuban missile crisis.

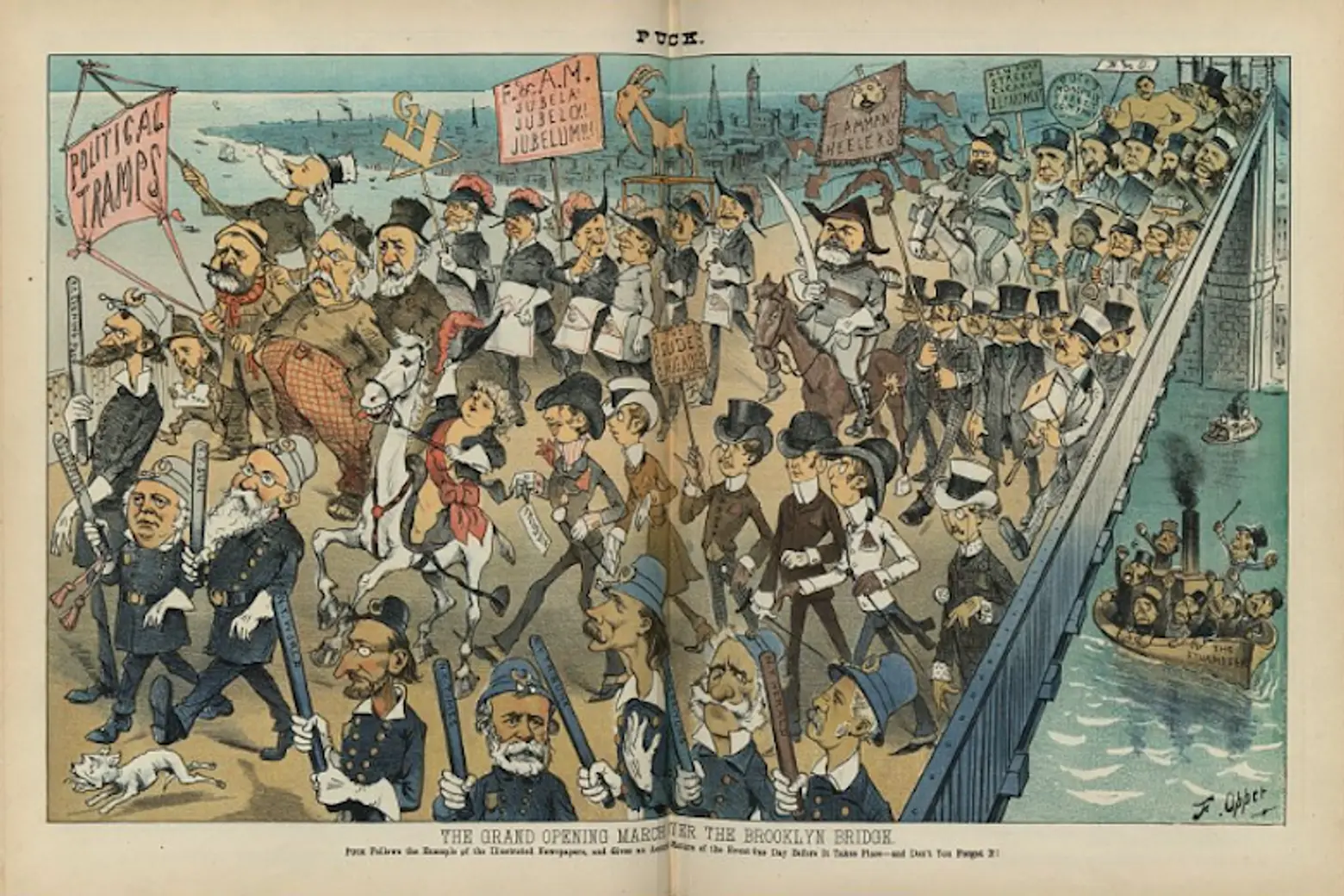

Opper, Frederick Burr, Artist. The grand opening march over the Brooklyn Bridge / F. Opper. N.Y.: Published by Keppler & Schwarzmann. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Digital Collections

7. A fatal stampede caused New Yorkers to doubt the bridge’s strength

Only six days after the bridge opened, a woman tripped and descended the wooden stairs on the Manhattan side of the bridge. As the story goes, her fall caused another woman to scream and those nearby rushed towards the scene. The commotion sparked a chain reaction of confusion. More people mobbed the narrow staircase, and a rumor that the bridge would collapse began in the crowd. With thousands of people on the promenade, a stampede caused the deaths of at least twelve people.

8. But a parade of elephants quelled any doubts

When the Brooklyn Bridge was gearing up for its opening day, P.T. Barnum proposed to walk his troupe of elephants across it–but authorities turned him down. After the stampede, however, there remained doubts that the bridge was indeed stable. So in 1884, P. T. Barnum was asked to help squelch those lingering concerns, and he got the opportunity to promote his circus. His parade of bridge-crossing elephants included Jumbo, Barnum’s prized giant African elephant.

As the New York Times reported at the time, “At 9:30 o’clock 21 elephants, 7 camels, and 10 dromedaries issued from the ferry at the foot of Courtlandt-Street… The other elephants shuffled along, raising their trunks and snorting as every train went by. Old Jumbo brought up the rear.” The paper of record also noted that “To people who looked up from the river at the big arch of electric lights it seemed as if Noah’s Ark were emptying itself over on Long Island.”

9. This bridge inspired the saying “I’ve got a bridge to sell you,” because people were actually trying to sell the Brooklyn Bridge

Con artist George C. Parker is supposedly the man who came up with the idea of “selling” the Brooklyn Bridge to unsuspecting visitors after it opened. His scam actually worked, as it is said he sold the bridge twice a week for two years. Reports say he targeted gullible tourists and immigrants. (He didn’t just put a price tag on the bridge, he also “sold” off Grant’s Tomb, the Statue of Liberty and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.) Parker’s success convinced other conmen to try their hand at selling the bridge, but none were as successful. The sensation, however, inspired the phrase “I’ve got a bridge to sell you.”

Parker did see consequences for his scamming: after being arrested for fraud a few times, he was sent to Sing Sing for life in 1928.

New York and Brooklyn Bridge: Promenade. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, Digital Collections

10. Despite its strength, the bridge still moves

Even today, the Brooklyn Bridge rises about three inches if it’s extremely cold. It’s a result of the cables contracting and expanding in cold temperatures, which has happened ever since the bridge was completed.

But you’d be mistaken to think the cables don’t have super-human strength. Each cable is made of 19 separate strands, each of which has 286 separate wires. (There are over 14,000 miles of wire in the Brooklyn Bridge.) To install the cables, workers would splice wires together, then tie them to make the strands. A boat would come from Brooklyn and sail it across to the Manhattan side. Then, two winches on the outside of the towers would hold the strands in place as workers raised them to the top. This tedious process, often interrupted by weather, took two years to complete.

Editor’s note: The original version of this post was published on May 24, 2018, and has since been updated.

RELATED: