Soho and Tribeca’s windowed sidewalks provided light to basement factory workers before electricity

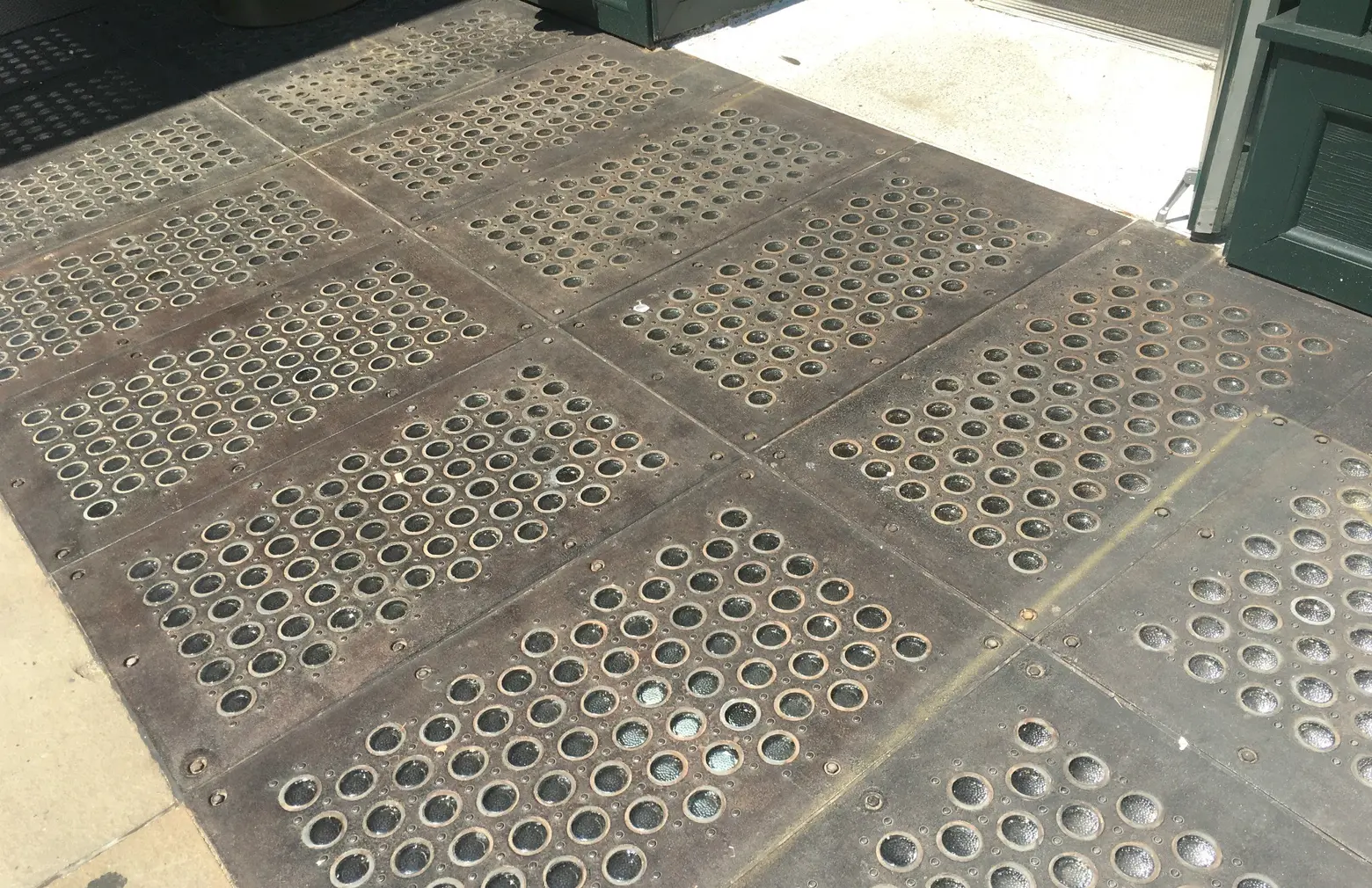

Vault lights in Soho, via WooJin Chung for 6sqft

In many parts of Soho and Tribeca, the sidewalks are made from small circular glass bulbs instead of solid concrete. Known as “hollow sidewalks” or “vault lights,” the unique street coverings are remnants from the neighborhood’s industrial past when they provided light to the basement factories below before electricity was introduced. These skylight-like sidewalks first came about in the 1840s when these neighborhoods were transitioning from residential to commercial and when their signature cast iron buildings first started to rise.

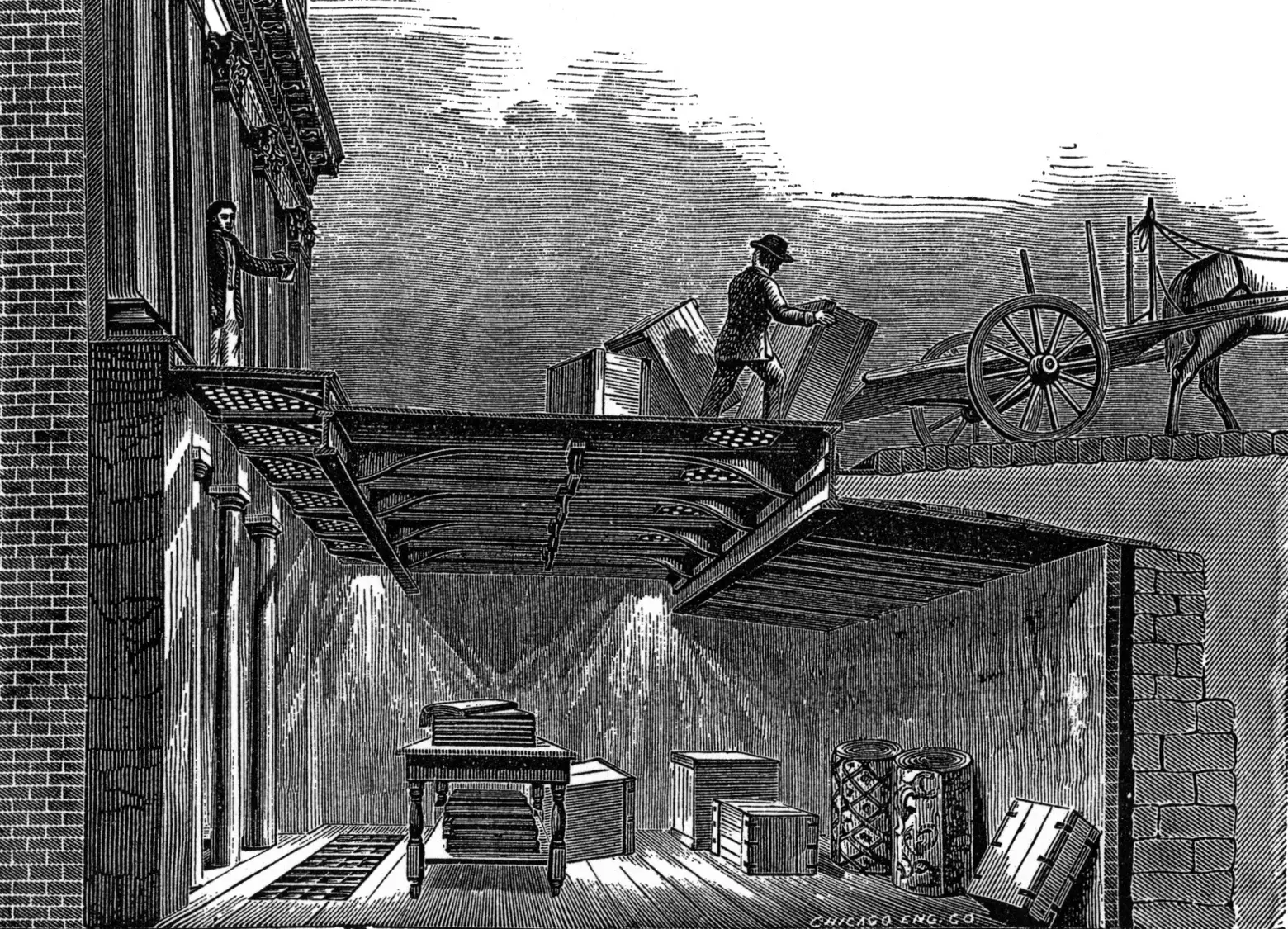

An illustration from an 1880 broadsheet advertising “Hyatt’s Patent Illuminating Tiles.” Illustration courtesy of Ian Macky/Glassian.

An illustration from an 1880 broadsheet advertising “Hyatt’s Patent Illuminating Tiles.” Illustration courtesy of Ian Macky/Glassian.

As part of the neighborhoods’ shift, a new type of building that combined office, manufacturing, and retail spaces became common. While businessmen sat in the offices above ground, immigrant workers populated the basement factories, or vaults, below. Since there was no electricity, the first way building owners sought to bring light down into these subterranean spaces was through sidewalk skylights. But as Tribeca Trib explains, “the skylights and their support frames typically blocked the sidewalk or loading dock and even obstructed a building’s entrance.”

So in 1845, Thaddeus Hyatt, an abolitionist and inventor, patented a system of setting round pieces of glass into cast iron sidewalks. His “Hyatt Patent Lights,” as they were often called, were technically lenses, since their underside had a prism attached to bend the light and focus it to a specific underground area. Hyatt eventually moved to London and brought his lights with him, opening a factory there and having them produced in cities throughout England. The lights brought him great wealth, and he went on to also patent several designs for reinforced concrete floors.

The use of vault lights decreased when electricity arrived and they became expensive for property owners to maintain. And with years of neglect, some of the metal frames began to corrode, and the tiny glass windows were deemed hazardous. Since then, many have been filled in with a variety of materials including concrete and stone, though some still remain untouched in their original form; a great example can be found at the intersection of Greene and Canal Streets, as well as in Tribeca at 119 Hudson Street, 155 Franklin Street, and 161 Duane Street.

RELATED:

Interested in similar content?

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published.

When the Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture – led by the redoubtable Margot Gayle – ran regularly scheduled tours of SoHo in the 1970s and later, the guides (I was one) always pointed out the vault lights – some of which still bear foundry marks. The Landmarks Commission considered them so important to the SoHo historic district’s character that the official designation report (http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/0768.pdf) includes a separate section devoted to their history with street-by-street listing of each one (p.190 ff).