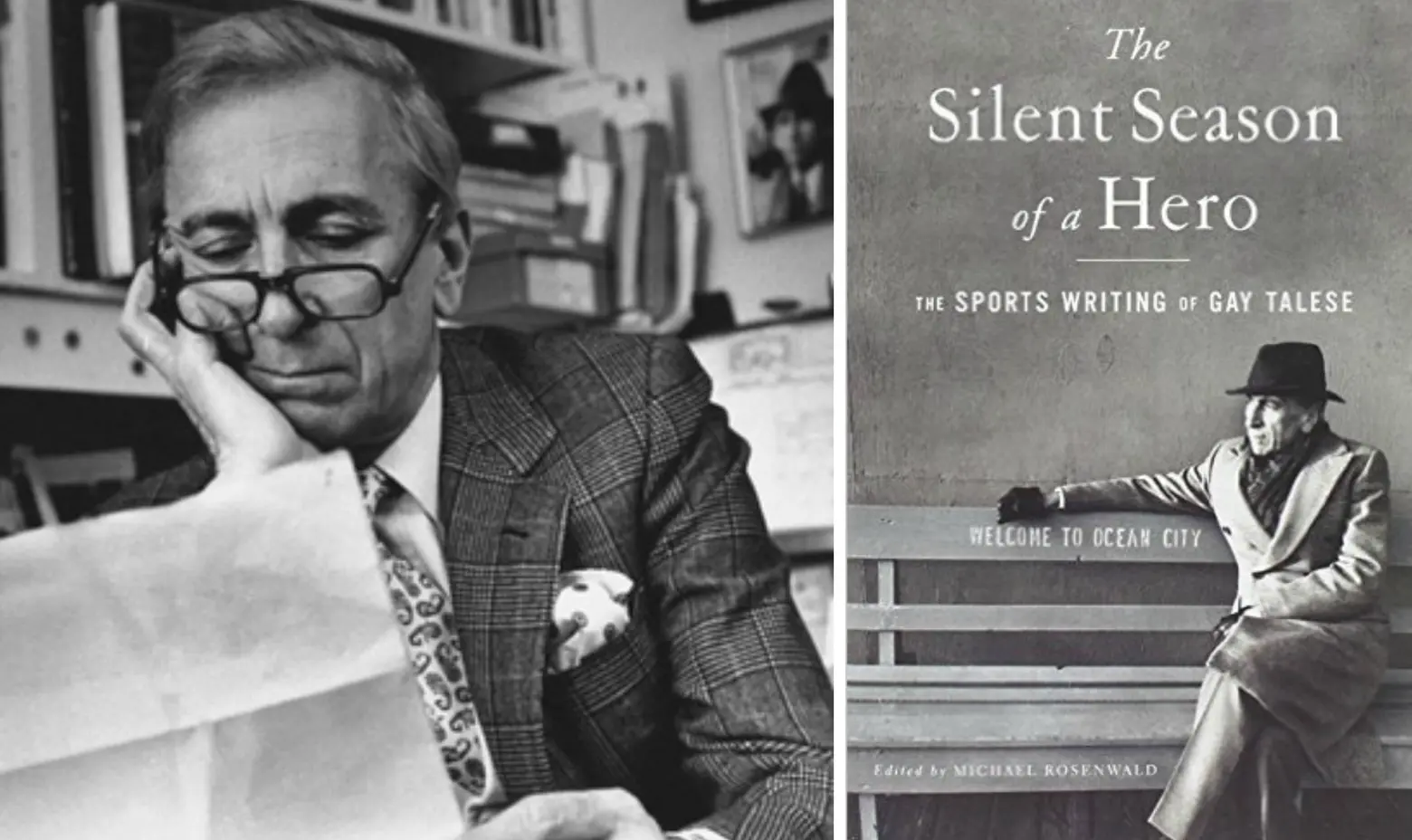

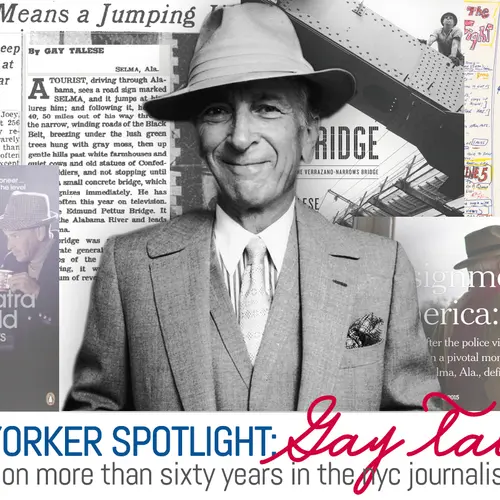

Spotlight: Author Gay Talese Reflects on More Than Sixty Years in the NYC Journalism World

“I was very curious as a grade school kid and that curiosity never abated,” explains renowned writer Gay Talese. This curiosity has been both a driving force and a constant throughout Gay’s more than 60-year writing career; a career in which his observations and discoveries have been widely read and published.

Gay’s first forays into writing were for his hometown of Ocean City, New Jersey’s local paper in high school. After graduating from the University of Alabama, where he had written for the school’s paper, he was hired as a copyboy at the New York Times in 1953. For Gay, this job laid the groundwork for a career in which he was a reporter for the Times, wrote for magazines such as Esquire (where his most famous pieces on Frank Sinatra and Joe DiMaggio were published) and The New Yorker, and published books on a wide variety of topics including the construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. 6sqft recently spoke with Gay about his career and the changing landscape of journalism.

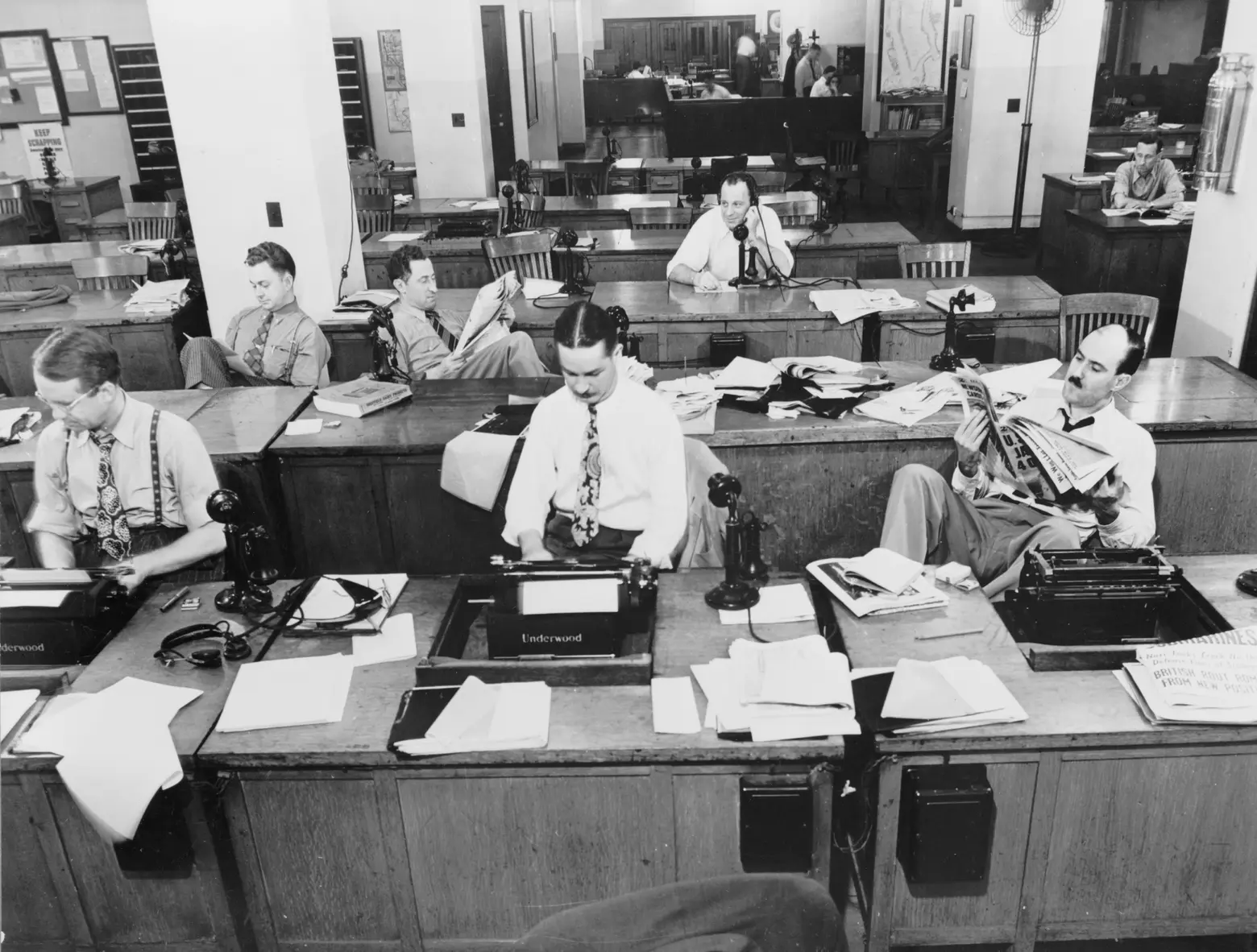

The New York Times newsroom in 1942

What was it like to be a copyboy at the New York Times in 1953?

For me, it was an exciting time, maybe the most exciting time in my life because I was 21 and I had never been in New York before. I was just enamored of the New York Times because it represented the very pinnacle of the print media in journalism. The building itself was an enormous, grey stone gothic building on 43rd Street between Broadway and 8th Avenue. It had much of the appearance of a great cathedral, and I had a very active Catholic background. I was an altar boy, so I had a strong sense of religiosity.

The institution was committed to being a paper of record. I thought of the paper of record akin to being like monks in a monastery working on scroll, keeping a record and writing in ways that were supposed to be retained for the future. The idea of eternity was very much in the mind of young people like me because I thought what you wrote or covered would be read 100 years later. I didn’t think in terms of daily journalism as a preoccupation with my own time, but rather what I did would be visited upon me and other people many, many, many years in the future.

How did this job affirm your desire to become a journalist?

My job as a copy boy was a servant in the great institution. I would go out and buy coffee or sandwiches for some of the copy editors or I would carry messages up and down the building. It was a 14-story building and during my rambling up and down the elevator and through the halls, I would see not only newspaper people, but on different floors advertising people, circulation managers, editorial writers, and on the top floor the executives and owners of the paper, the family Sulzberger. I was observing the faces, how people spoke, what the rooms looked like, what books were on the shelves. All of this was rather ecclesiastical. I had an exalted sense of self. It wasn’t a job. I had a calling.

In my off hours, I would write things myself – I wasn’t assigned anything because I wasn’t a reporter. I would write things that I saw around the city and give them to editors and sometimes they’d publish what I did. I had a magazine piece as a copyboy pushed in the Sunday New York Times magazine. I had a piece on the editorial page.

Following time in the military, the Times hired you as a sports reporter. What did this teach you as a journalist and more broadly, about society?

It was the most broadening experience. In all of journalism, whether you’re talking about war reporting or police reporting or business reporting, religion reporting, the only reporter who sees what he’s writing about is the sports reporter. You go to a football game, a prizefight, a tennis match or a baseball game, and you’re actually there in the press box on the sidelines. Later on you’re in the locker room. You talk to a prizefighter who you saw knocked out and if he’s not inarticulate, he will say he didn’t see this punch coming. Or the guy who struck out when the bases were loaded and you later talk to him in the locker room, you actually see and hear; you’re right on top of these people, and as such, you see their faces. You actually see them as they react to or recall what happened an hour before.

It’s also not only sports that you’re covering; you’re covering social mobility, anthropology, political and social trends. You have a sense of the vigor and vitality of people who are coming from places of poverty or lack of opportunity and they find their opportunity in the world of sports and sometimes become affluent and famous. And also in sports, if you lose too much you lose your job. You see the tragedy, the economic results of being unsuccessful.

All told, you spent about a decade at the Times. How did this impact the rest of your career?

Well, the first thing I got was responsibility to the facts. It’s not enough to be a good writer. It’s not enough to be an attention-getting writer with style or the air of a dramatist. Journalists are not dramatists. They’re not supposed to be entertainers. They’re supposed to be serious chroniclers of what they see and understand. They must understand what they’re seeing and they must see to understand it. Or if not seeing it, getting very good information from many reliable sources to confirm the fact that what they’re writing is as close to the truth, if not the total truth, as it can be verified. I learned first to get it right, not to get it fast. I don’t want to beat everybody. I want to beat them at making it best: the best written, the best reported, the most honest, the most comprehensive.

You were part of New Journalism of the ’60s and ’70s. How did you find yourself working in this style?

I didn’t know it was new journalism. I always practiced old journalism and that is being there, showing up, just walking around. But I also had ideas about good writing. I would read good writers, most of whom were fiction writers–F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Faulkner, short story writers like John Cheever of The New Yorker, Irwin Shaw. What I wanted to do was take the techniques of the storytelling fiction writer and bring to newspapers the same structure of storytelling, but making sure the story stays true.

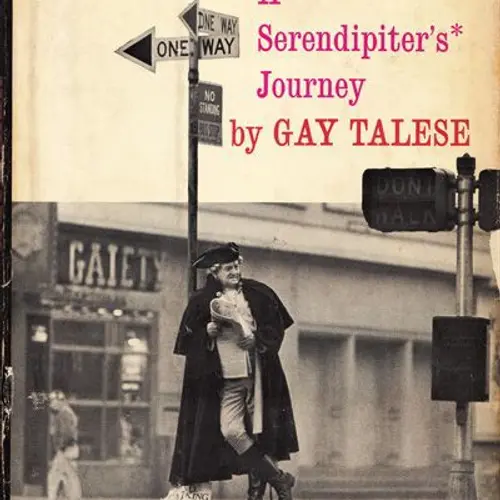

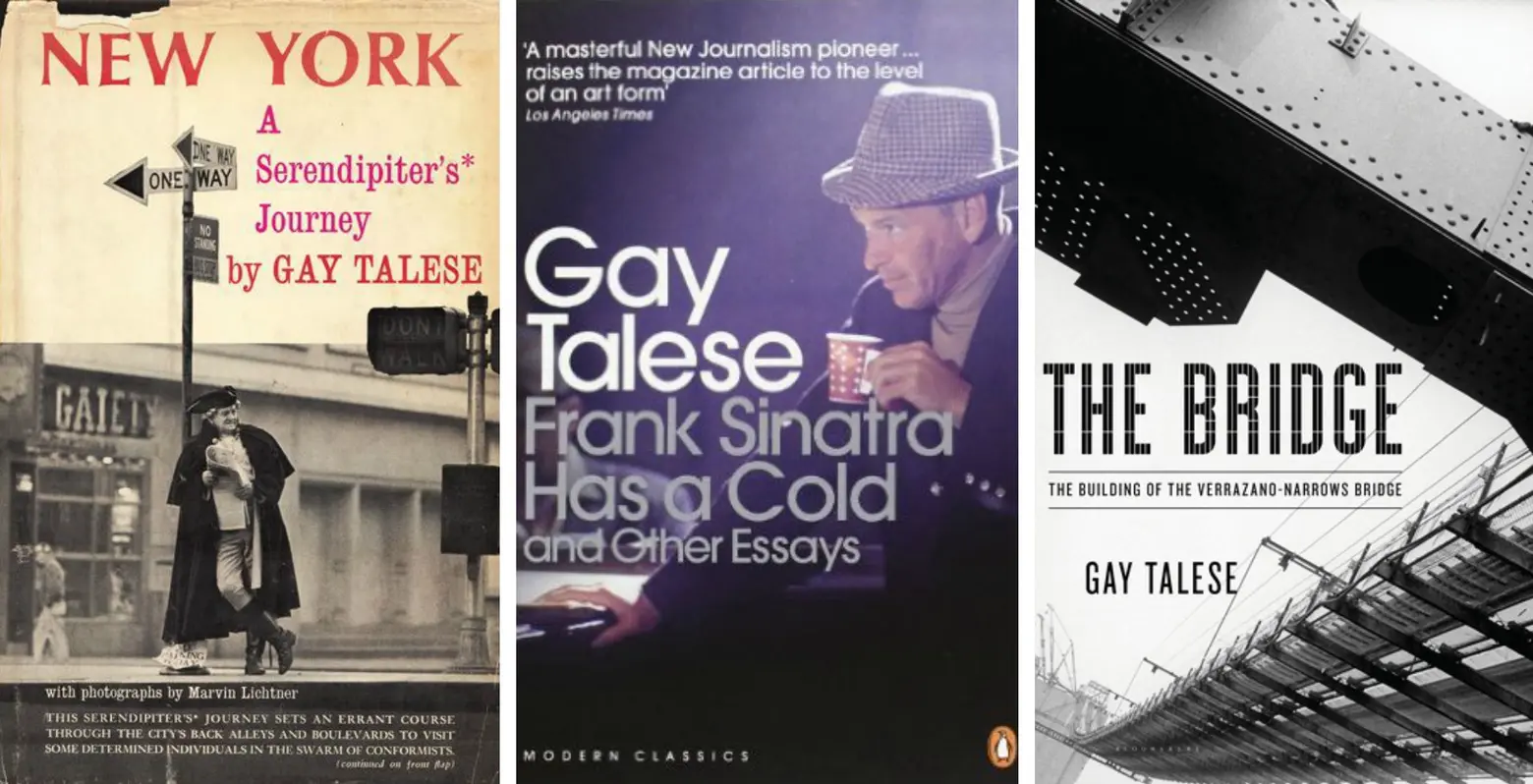

Covers of three books by Gay Talese

What inspired your first book “New York: A Serendipiter’s Journey?”

I was really like a man from the provinces. Here I am from Ocean City, New Jersey, a town in the wintertime of 5,000-6,000 people, small town, one main street, everybody knew one another. Then I end up in a city of 8-9 million people. And I’m walking the streets of the city and I’m in the shadows, in the sun, I’m under tall buildings or I’m under a bridge, or I’m crossing the street, I’m walking down an alley, I’m going up an escalator, going into Macy’s. I’m all over the place and I see things and I think, “Ah, they’re interesting.” They’re the stories of the unknown, the stories of obscure people, the stories of you tend to overlook.

For example, a doorman. I write a lot about doormen. Most people never pay attention to the doorman. They live in a building that has a doorman and walk in and say, “Hello Harry, Goodbye Harry.” They don’t know who Harry is. I know who Harry is because I talk to him; I write about him. Serendipiter has stories about doormen, elevator operators, charwomen in the skyscrapers. It’s about the pigeon feeders, barges that come and go on the East River, the bridges. It was a warm up and indulgence to my curiosity about the city of New York.

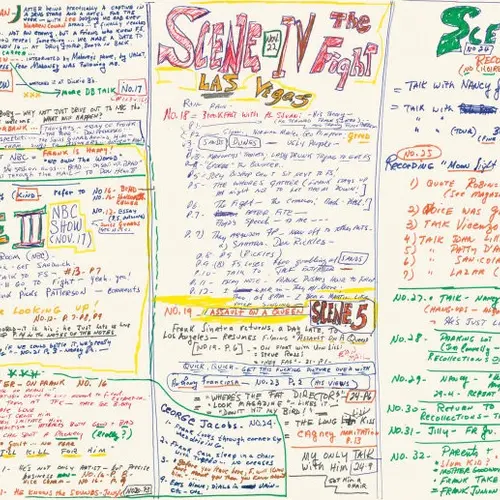

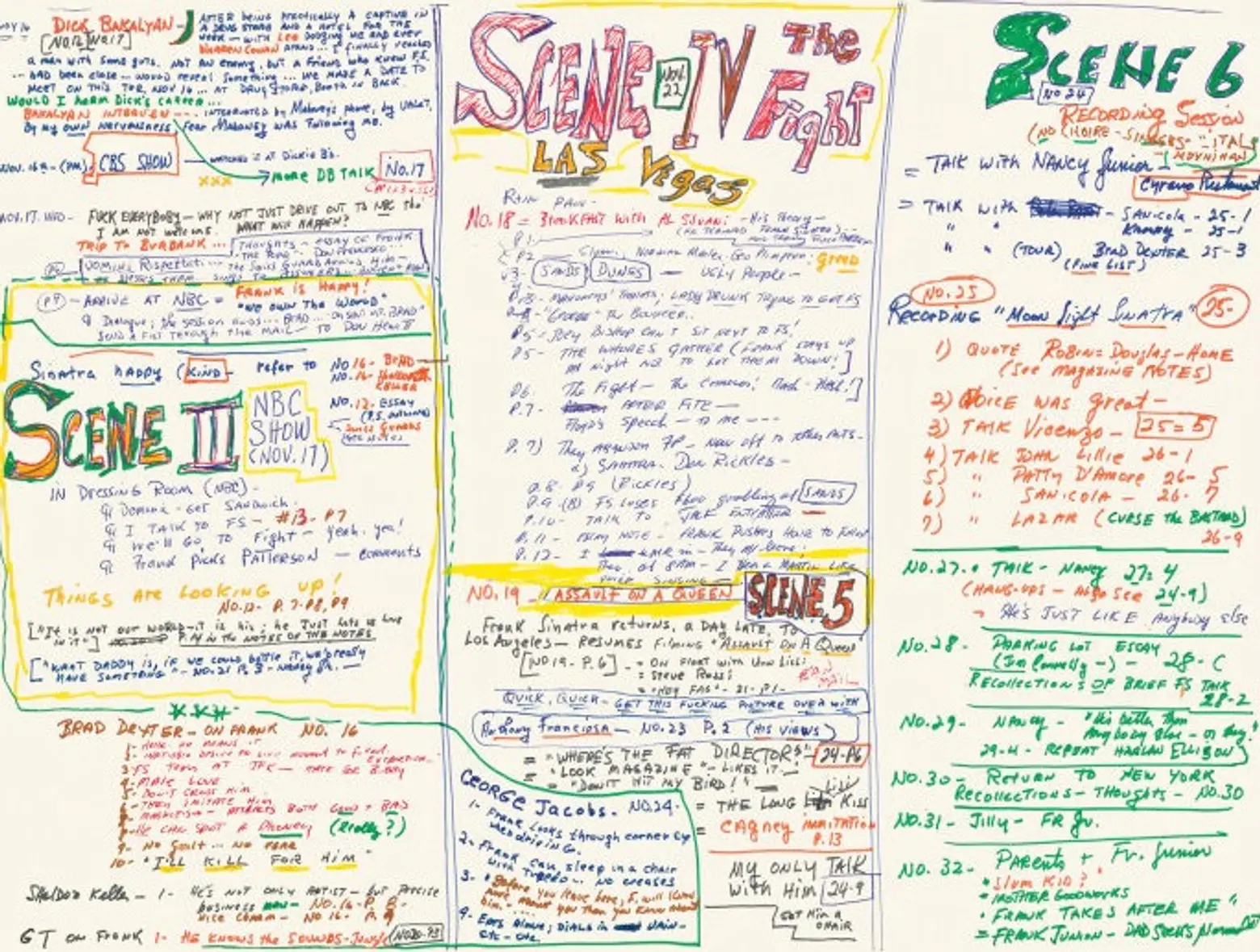

The original outline for “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”

You wrote a piece for Esquire magazine about Frank Sinatra. What was is like to cover him?

Well I wrote hundreds of magazine pieces, newspaper articles, and more than a dozen books, and it’s all the same. What is it like? It begins with curiosity and then it moves to activity, finding out who these people are, what are they like, hanging around. It’s the art of hanging around. Sinatra, I didn’t talk to him, I hung around. He didn’t want to talk to me; I hung around and watched him try to record a song in a studio. I watched him attending a prizefight in Las Vegas. I watched him sitting at a bar in a Los Angeles nightclub with a couple of blonde women having a drink and smoking a cigarette. The beginning of that piece is a description of just that about Sinatra having a cigarette, having a drink at a bar with two blondes. The music in the wee small hours of the morning was on a record player. There’s no questions in that piece. It’s all observation, storytelling, like a novel, or it could be the opening scene of a movie.

You have been a participant and observer of journalism for a long time. How has journalism changed?

Well, I think that great journalism doesn’t change. It’s great or it’s not great. That could be 1920; that could be 2016. But I think that there’s a tendency now to do things very quickly and the technology allows that to happen whereby you sit at a laptop and you can get a lot of information from just googling it and you don’t see it. What they’re doing is staying indoors and looking at their laptops or carrying their laptops around with them. And they’re seeing a screen and they’re really not seeing beyond it. They should go out and see people personally. They should spend time with them and not be in such a rush.

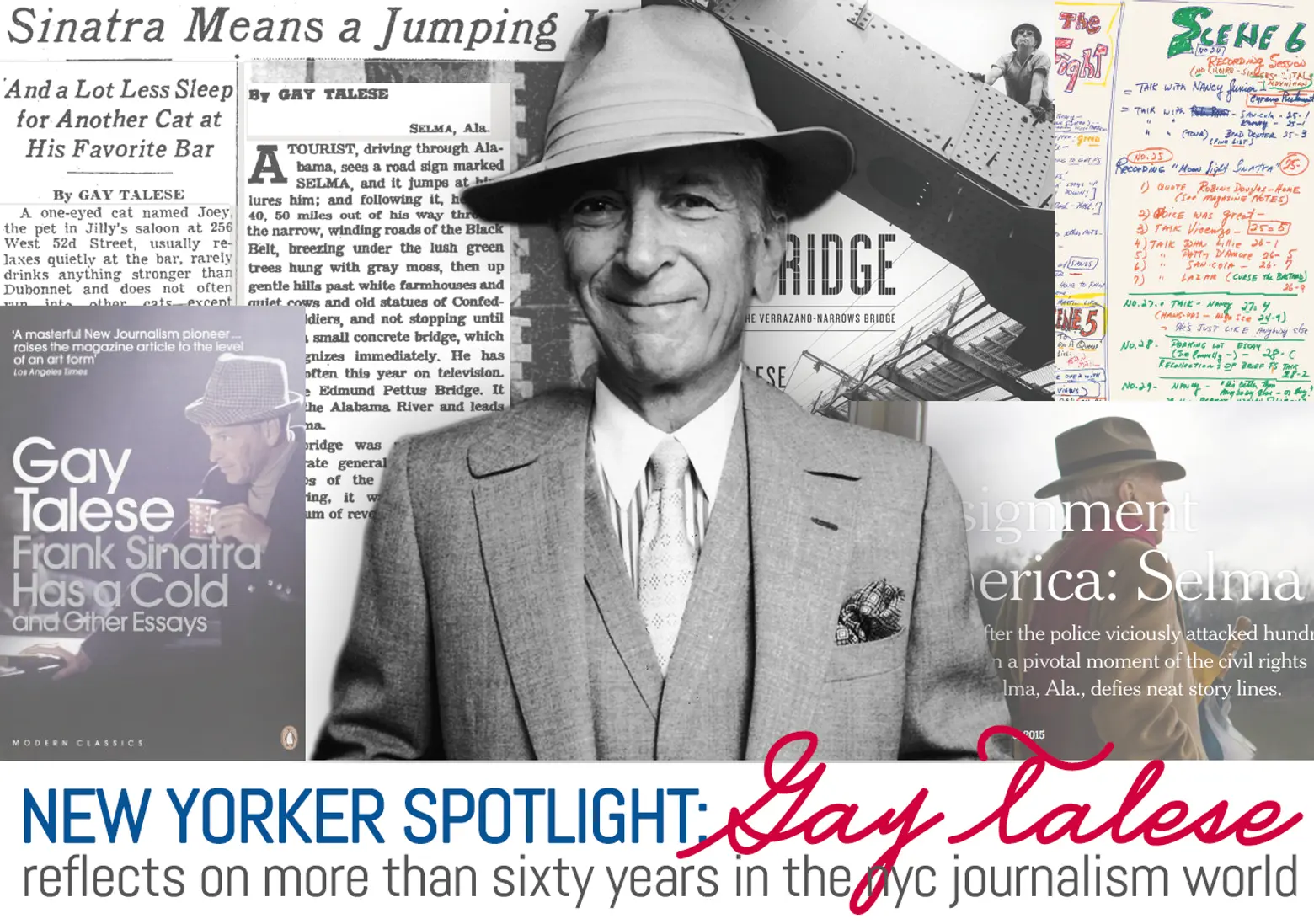

From the online version of Assignment America: Selma

From the online version of Assignment America: Selma

Do you have a favorite story or one that stands the test of time?

When I was a reporter in 1965 my last story for the Times was the Selma March, and then 25 years later I wrote about that same story. Last year when it was 50 years later I was called by the paper to do a story in Selma, Alabama. I went down there and wrote a story. I was 83 and felt like I was 23 because I did those kinds of stories when I was 23. That was a story about a black man who was carrying a shovel and he was putting plants along the sidewalk on Main Street in preparation for the arrival of President Obama. He was beautifying the streets and putting shrubbery here and there. The whole story begins with him and that is because I was there and saw this guy and thought it was interesting. I talked to him and got him to tell me things.

I had a piece on the cover on March 6, 2015. Even now, there’s nothing quite like when you have a story published and you just started working on it a couple of days before. There’s immediate gratification, pride in being published, pride in doing a well done job. If I had to recommend a job to anybody I would say be a journalist because you learn about all kinds of people. You meet every different kind of person in the course of a year. It’s like going to a great university, you’re tutoring, auditing courses through the eyes and minds of people of accomplishment. It’s a wonderful way of going through your life.

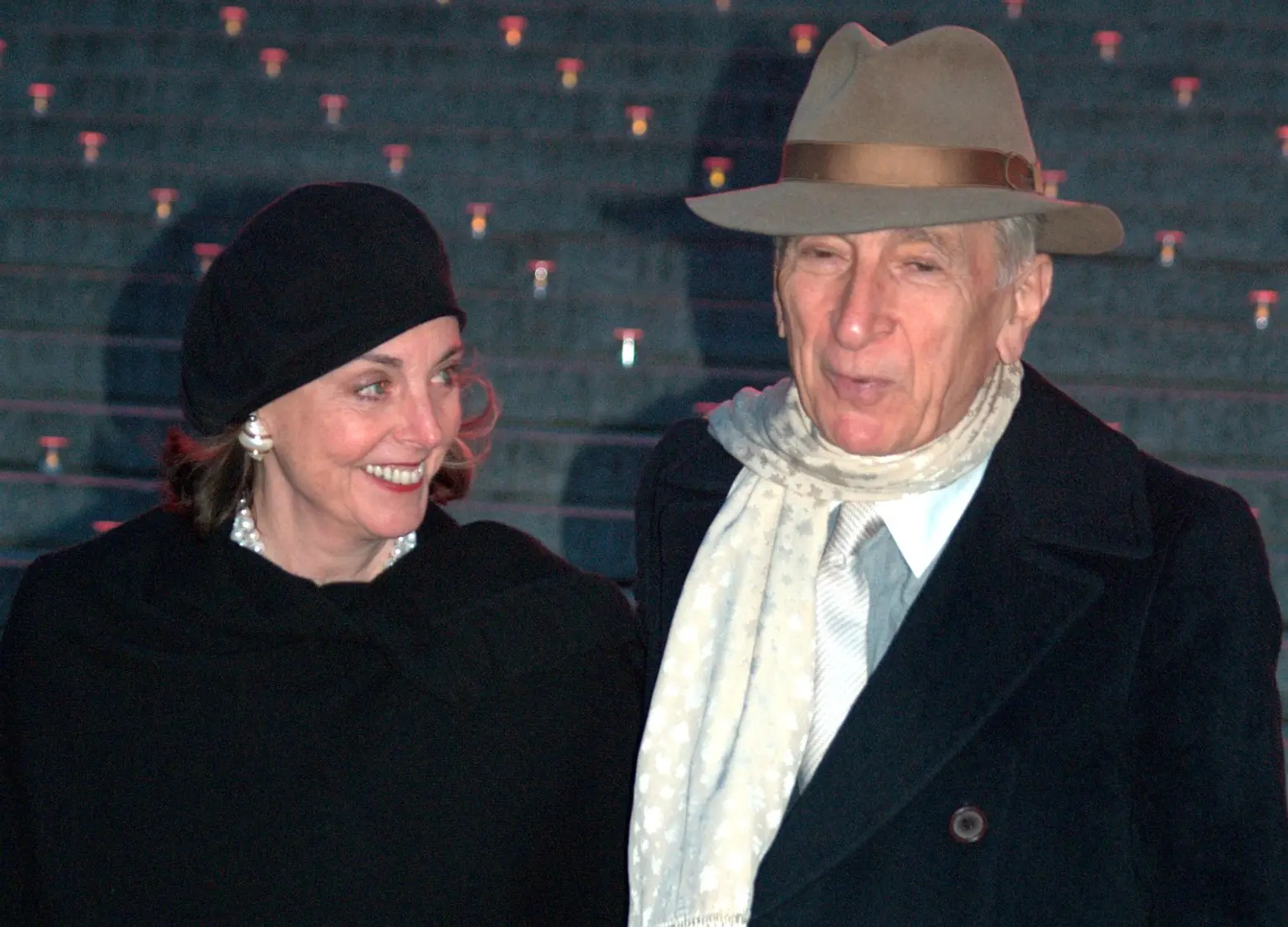

Gay and his wife Nan at the 2009 Tribeca Film Festival

Over the last 60 years, what have you learned about New York?

They say that life changes, yeah, that’s true, but a lot of life doesn’t change. A lot of things, especially things of a certain enduring value, remain. My block on the east side of Manhattan today pretty much looks as it did when I first moved into it in 1957. On this street, I have a history of the neighbors that I know. I know the history of businesses, some of them have come and gone. I remember restaurants that were on my block replaced by other restaurants. I know hat shops and dry cleaning shops. I know people who have dogs and what the dogs look like and sometimes the names of the dogs. It’s really a small town. It’s a little neighborhood. It has its personality, it has its names, its stores, its architecture. And so, yes, it’s New York, yes it’s a city of eight million, but it isn’t a city that’s faceless or without a sense of individual humanity or a sense of place and identity. It’s very personal.

+++

[This interview has been edited]

RELATED: