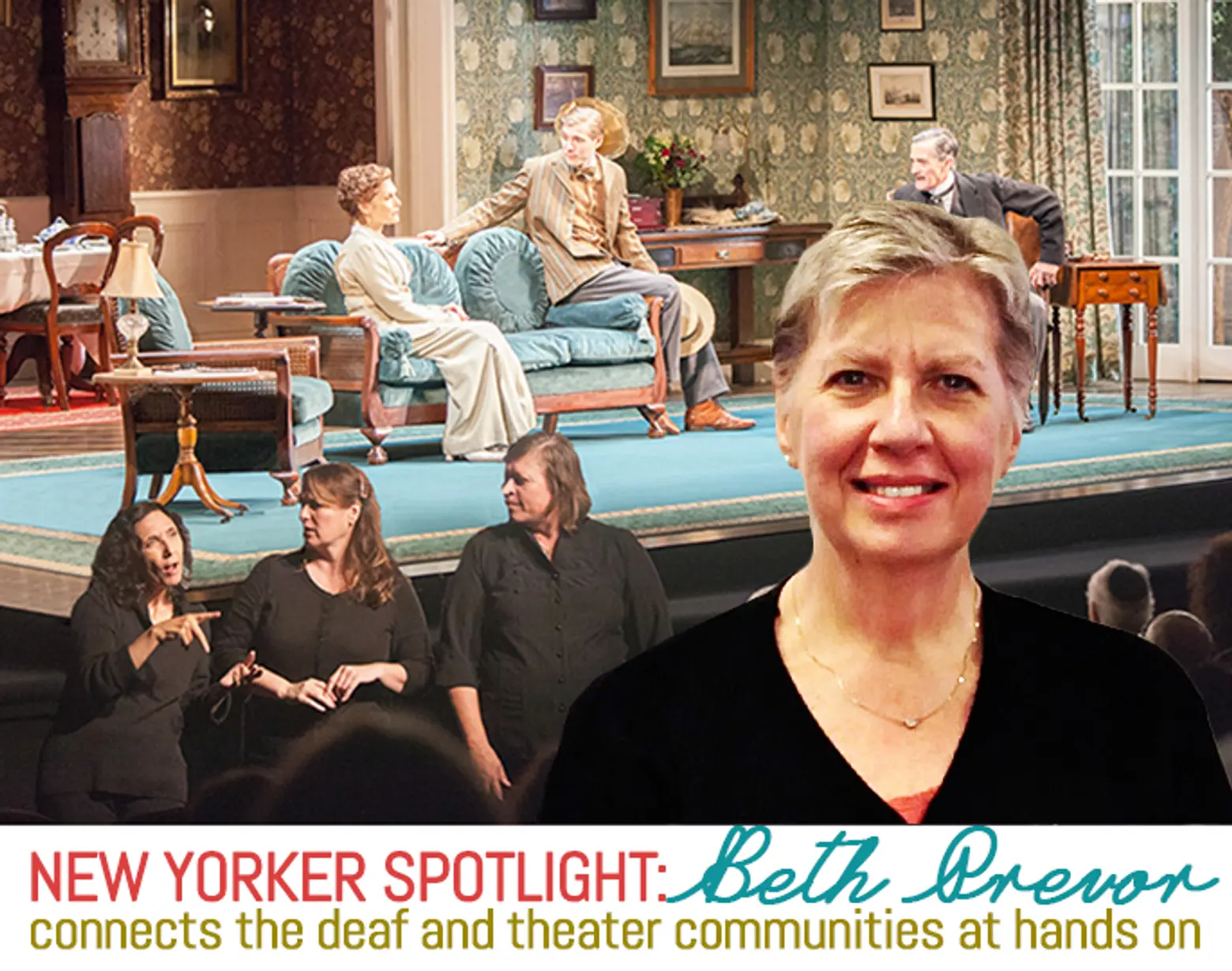

Spotlight: Hands On’s Beth Prevor Connects the Deaf and Theater Communities in NYC

Beth Prevor and Roundabout Theatre’s production of “The Winslow Boy”

When New Yorkers plan a night at the theater, they likely focus on snagging the best seat in the house. For deaf theatergoers whose first language is sign language, attending a musical or play is a bit different, as they require an interpreter to sign the drama and humor. For a long time, accessibility to interpreted performances was limited, but thanks to the organization Hands On, the deaf community now has the opportunity to attend numerous off-Broadway and nonprofit theatrical happenings in the city. In addition to providing access to interpreted performances, Hands On also creates a master calendar of all local cultural events open to the deaf community.

Beth Prevor is one of the nonprofit’s founders and serves as its Executive Director. She first became interested in bringing the theatrical and deaf communities together after serving as a stage manager for a production that included deaf performers. Over the last 30-plus years, her work has helped change the city’s arts landscape for deaf individuals. We recently spoke with Beth to learn more about Hands On’s work, the challenges of interpreting theater, and the organization’s goals for the future.

You began your career working as a freelance theatrical stage manager. How did you become involved with the deaf community?

In the late ‘70s, I got involved stage managing for an educational theater company with deaf and hearing performers that was touring schools. It was my first exposure to deaf people and sign language. I just thought it was really interesting and I wanted to continue learning more, so I started taking sign language classes, and from there I went to an interpreter training program. I am a certified interpreter, but that was never really my goal. My goal was to understand and learn the language and to combine theater and sign language together.

What inspired you to co-found Hands On?

I don’t even know if this was the impetus for Hands On, but I do remember different periods when I was stage managing where there was just a feeling that sometimes people who had access to theater were not excited about it. I think when I started getting exposed to deaf people and seeing what wasn’t available, it made it more clear to me that there was an area not being covered. I thought it would be great if we could do something that other people weren’t doing and provide access to those without it.

There were four founding members: myself; Janis Cole, a deaf actress; Janet Harris, who is an interpreter and on our board, but now lives in San Francisco; and Candy Broecker, who continues to work with me on Hands On, running our program at the New Victory Theater. Candy’s parents are deaf and she’s a wonderful sign language theatrical interpreter. We [co-founders] really looked at what the Theatre Development Fund was doing on Broadway with interpreting some shows, but no one was really focusing on off-Broadway and the nonprofit theater community. When we started Hands On, we wanted to open that part up to the deaf community. The four of us took our address books and put together a list of all the people who we knew, and that’s how we created our mailing list. It just started spreading from there.

What were the first theatrical productions the organization was involved in?

One of the first things that we did was with Dance Theater Workshop in Chelsea, which is now New York Live Arts. I remember they were having a production of Musign, a company of deaf performers that did sign language with music. And we found out about that and we went to Dance Theater Workshop and we offered ourselves up as volunteer ushers to help with the audiences because they would get a really big deaf audience for their shows. After, they were interested in doing some more programming with us.

The very first show we worked as interpreters for them was the Traveling Jewish Theatre, but the really big thing we did with them was one of the first performances with Whoopi Goldberg, and this was when she was just starting out in New York. Whoopi had an interpreter who worked with her and stood next to her, and her show that night became a two-person production. That to me was really where we started. Subsequently, we ended up creating a piece for a deaf performer named Mary Beth Miller at Dance Theatre Workshop, which was the beginning of a national theater of the deaf.

How did Hands On evolve into the organization it is today?

The Alliance of Resident Theatres of New York actually took us on as a consulting group. One of our first projects was with the Manhattan Theatre Club. We thought we would go into the theater companies, explain to them how to do an interpreted performance–this is what the interpreters needs to do and how to hire interpreters–and then they’d take over. But the theaters generally came back to us and said, “It would be much better if we hired you to do it.” So that’s how we got started, and Circle in the Square and Manhattan Theatre Club were two of the early theaters we worked with in the early to mid ‘80s.

Deaf West Theater’s Spring Awakening

Deaf West Theater’s Spring Awakening

When a production is interpreted, what are the goals?

You want as similar an experience to the hearing audience as possible; that’s the goal. It’s probably never going to be an exact experience because you’re getting it through an interpreter, but you don’t want it be less opaque to them than the regular audience.

Along those lines, what are some of the challenges?

We just did a production of Harold Pinter’s “Old Times” at the Roundabout Theatre. Doing an interpretation of a show where at the end any person’s interpretation would be valid was an incredible challenge. When the show is over, you start questioning if it’s real. If everybody is leaving the play going, “What just happened?” and everybody’s interpretation is valid, then how does an interpreter interpret something without putting his or her own interpretation on it? You don’t want the reason why it’s not definitive to be because you’re deaf, but rather the play itself. Roundabout has this wonderful dramaturg, Ted Sod, and he met with the interpreters to talk about how you come up with an interpretation that still leaves the message up to the audience.

I think what’s happened over the last 30-plus years is the creation of a sophisticated deaf audience. When we first started this, what would end up happening is people would comment on the interpretation. They liked the interpreter, they didn’t like the interpreter, and so it became much more a commentary on the interpreter rather than a commentary on the play. What we see now, which is fantastic, is people will say, “I didn’t like the play.” That’s what you want.

Who are some of the theater companies you have worked with over the years?

There’s a small, but incredibly loyal number of theaters that we work with and have worked with for a long time. We work with Roundabout Theatre Company, and I think we are going into our 20th year with them. We have a subscription series with them and we basically interpret every show that they do. We do Shakespeare in the Park every summer, and we’ve done that for I think 32 years. We get so many deaf people there; it’s really become an amazing community event, something for which people come from out of town. At New Victory Theater, we do their entire season and have public performances and educational shows with the schools for them. We started working with the Atlantic Theater Company last year. We’re also starting to do some workshops for theatrical interpreters because we realize that we need to expand the pool of interpreters. I think this is the next step.

Deaf West Theater’s Spring Awakening

Deaf West Theater’s Spring Awakening

Deaf West Theater has brought back Spring Awakening for a limited run on Broadway in which hearing and deaf performers are acting together on stage. How major is this production for the deaf community?

It’s a different kind of experience for the deaf community. Historically, deaf people do not have a lot of regular access to Broadway. So the idea that you’re not buying tickets in a specific section, you don’t have to wait for an interpreted performance, suddenly now deaf people can just be theatergoers.

I just did a workshop about disability, access, and audiences, and I started off by talking about how there are deaf people on Broadway as well as a wheelchair users on Broadway, and it’s bringing deafness and disability to the forefront. The interviews and articles going on, it’s just fantastic. The hope can only be that this is going to springboard more people demanding access.

Why is this production also important for those outside the deaf community?

I think it’s incredibly important because in this society there are still people who are not as open as they should be. The visibility of seeing deaf people on stage, deaf people in the audience, it’s going to help us in so many bigger ways than we know.

There are several Broadway shows that offer captioning services. How does captioning differ from interpreted performances?

Captioning is incredibly important and serves a large community of not only deaf people. I am a supporter of sign language and that’s what we do, but the i-caption is important in that it lets anybody go whenever they want to go. I think captioning has overrun sign language, especially at Broadway theaters, and that’s done a real disservice to a big part of the deaf community who continues to want the service. There is very little interpreting happening now on Broadway. We in the interpreting field recognize that and are trying to figure out how to expand it back again.

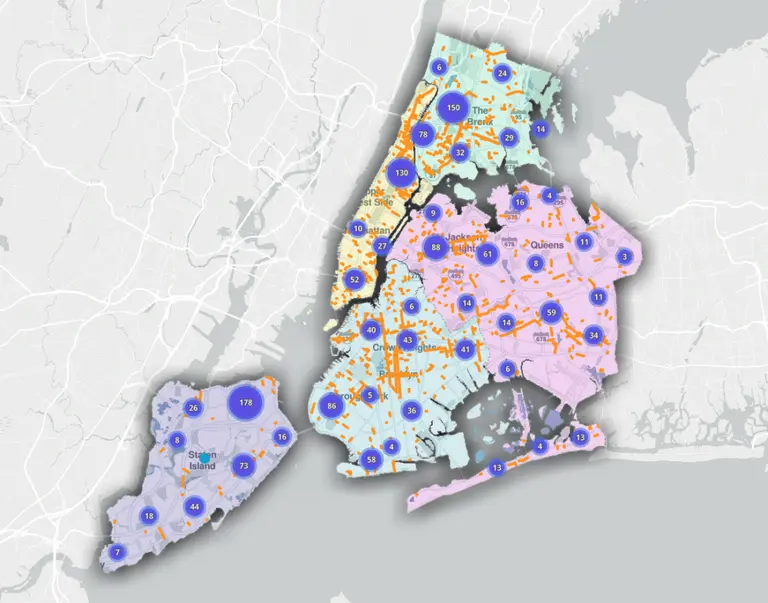

In addition to interpreting theater, Hands On produces a calendar that lists arts and cultural events in New York with deaf access. Why does the organization compile and create this resource?

I think that’s a big and important program that we do. We started doing this in ‘94 as a paper calendar that we’d mail out; now it’s online. We put any cultural event in New York City that’s accessible to deaf and hard-of-hearing people. Historically, one of the big issues, especially in a place like New York City, is that there’s no real centralized place for finding information. A lot of the museums do access programs for deaf and hard-of-hearing people, which is fantastic, but they do their own programs. For somebody just trying to find out what’s going on, we’re kind of it.

Does the organization have any exciting upcoming projects?

We’re definitely talking about policy. It’s something I’ve been interested in because there really isn’t any. No theater has any policy on access and what you do and how you do it. If someone wants to go to the theater and ask for an interpreter, can we do it? Especially with shows like Spring Awakening, you’re bringing a lot of young, deaf actors into the city who want to have access to a lot more shows than are being offered. How you provide that access is a big question. There’s going to be a greater need, and we’re trying to work with a lot more theaters on developing a policy together.

What does helping the deaf community mean to you?

I’m not deaf, and I don’t have deafness in my family. For a hearing person to be accepted into the deaf community as I’ve been is quite amazing. You go to a show and you know everybody and everybody hugs you; it’s a fun, enjoyable experience. I love the community aspect of it. For all the work that we do–and it’s hard work–working not only with the deaf communities, but the interpreters, it’s a very small, tight, lovely group of people.

I actually have my own disability, so it’s been really interesting for me. I’m taking a lot of things I’ve learned working with the deaf community into my own community, which has given me a better understanding of me as a disabled person.

+++

[This interview has been edited]

RELATED: