Spotlight: Rita McMahon Brings Avian New Yorkers Back to Health at the Wild Bird Fund

Photo via Charles Chessler Photography

When we think of bird life in New York, our minds usually wander to pesky pigeons, but there are actually 355 different species of wild birds who call the city home. A good number (pigeons, mourning doves, and mallard ducks, to name a few) are full-time residents, but there are also many who have the ultimate pied-a-terres, flying north to nest and raise babies in the spring or migrating south from the Arctic for the slightly warmer New York winters.

For years, if these birds were injured or sick, there was little help available, but everything changed when Rita McMahon became involved in the rehabilitation of wild birds in 2002. What began for her as caring for pigeons and sparrows as a rehabber, progressively grew into a calling and eventually a career. Through the support and encouragement of the veterinarians at Animal General on the Upper West Side, she co-founded and became the director of the Wild Bird Fund in 2005, which was then located in her apartment. In 2012, the organization opened its own facility on the Upper West Side and last year treated approximately 3,500 birds.

6sqft recently spoke with Rita to learn more about New York’s wild birds, how the Wild Bird Fund helps them, and ways New Yorkers can be more attuned to their avian neighbors.

A snow goose being led into the waterfowl pool, via Ardith Bondi

What are some of the reasons wild birds are brought to the Fund?

Window collisions are the primary killer, followed by cars, bicycles, cats and dogs, and pollutants. In two days time we had two red-tailed hawks come in who collided with the same building on 57th Street. We have up to ten birds at a time that we’re treating for lead poisoning from the environment. They come in lethargic and uncoordinated with head tremors, torticollis (twisting neck), ataxia (tripping gait) and even paresis of the legs (weakness). They are treated with DMSA, a human chelation medicine. Birds also get caught in the netting around scaffolding. This time of year is when most of our birds of prey come in. During their first year, life was pretty good here in the summer. That’s all they ever knew, but then suddenly it’s cold, the squirrels and the rats and everybody else are hiding, and they’re not eating well, so it’s like failure to thrive.

When an injured or sick bird arrives, what is the intake procedure?

Anywhere from 1-21 birds might come in a day. Right now we’re averaging eight a day. During the high summer it’s about 26. We have a rehabber on duty from 1pm on and they do an exam that includes weighing the bird and checking out all parts of its body. They will splint it if it has a broken leg; they will do lab work on its poop to see what parasites it might have; if it has an infection, then they write the diagnosis. We don’t have an x-ray machine yet, though, so we have to use other veterinarians’ machines for that.

Hedgwig the snowy owl, via Ardith Bondi

Hedgwig the snowy owl, via Ardith Bondi

At the moment, who are some of your patients?

We have our first snowy owl. He came down from the arctic circle, flew around looking for food, and got struck one way or another. He’s getting x-rayed at the Humane Society of New York along with a Cooper’s hawk–he’s the second one we have–as well as a red-tailed hawk who went off for a checkup after he had his wing surgically pinned and placed. [Update on the snowy: The x-ray showed that the he may have been shot, possibly at the airport. He has a deep penetrating wound not easily visible and some fragments in his shoulder.]

Caring for a wild turkey, photos via Ardith Bondi

Do they express appreciation during the healing process?

I can give you two cases that I found amazing. One was a big turkey with a compound fracture of his leg. He had to have his splint changed every other day because the wound had to be cleaned. We would lay him down on his side, and when we started taking off the splint he didn’t move. We cleaned the wound, re-splinted him, and put him down on the ground. He knew when that was being done that it was in his best interest not to move. He was here for a while, so maybe he learned.

Take this red-tailed hawk, who was a monstrous, big female who had stepped in tar. The tar was holding her talons firmly together, meaning she couldn’t really land or perch and she couldn’t catch prey and eat. The prospect of removing tar from the talons of a red-tailed hawk is not a happy one. So big, burly Joey held her, and Ruth and I each took one leg and used these long q-tips with mayonnaise to get the tar off. It dawned on us that she was cooperating, so we actually end up slopping mayonnaise with our own bare hands. The next day we put the towel over the bird, took her out, held the wings to the side of her body, put the fingers on each side of the leg, put her on her side, and out come her feet. She absolutely knew what we were doing and within the hour she went free.

Red-tailed hawk release, via Ardith Bondi

What happens when a bird is healed and released?

Release is fabulous. The bird generally never looks back to say thank you, and that’s okay. Oftentimes, if we send them right back to where they live, they go up in the air and do a victory lap right above.

A peregrine falcon, via Ardith Bondi

A peregrine falcon, via Ardith Bondi

New Yorkers see hawks and falcons around the city. How large are each of these populations, and why do you think they capture people’s attention?

We have a very healthy population of red-tailed hawks–12 alone in Central Park were counted during the Christmas bird count. There are over 20 nesting pairs of peregrine falcons in NYC. Our kestrel falcon population is also thriving, where in other parts of the country it is declining. Hawks and falcons are apex predators–sexy, beautiful birds that are highly visible and thrilling to watch in the air.

A snow goose rescued by a fireman, via June Gooch-Wagoner

A snow goose rescued by a fireman, via June Gooch-Wagoner

Who are the good samaritans out there rescuing wild birds?

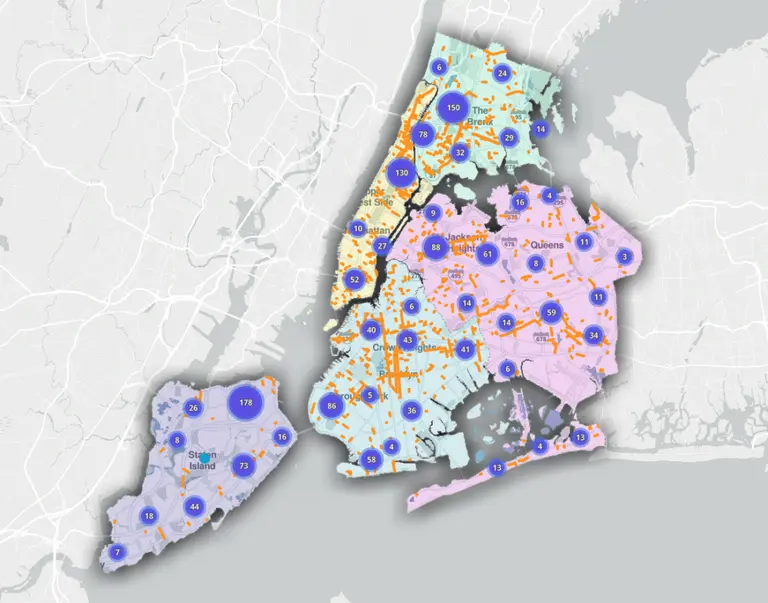

Everybody, and they come from the five boroughs, upstate, Long Island, Connecticut and New Jersey. We have several police stations that get birds regularly like the one down on Wall Street. The police love coming here because it’s a case and they get to write it up, but we always show them around. When a fire department person comes here with a bird, it’s a water fowl; a bird that deals with the water. When the police come, it’s always the big, nasty birds. It’s an association which I find bizarre and wonderful.

New York had a blizzard last weekend. What did birds do during the storm?

They hunker down and fluff up in their roost. A nest is where you raise babies; a roost is where you go to spend the night with your friends. They can eat snow to get their fluid. When it’s been really cold and there is no snow, birds suffer from dehydration.

What are some ways New Yorkers can help protect wild birds?

New York has done a better job, but we have to improve our environment. New York State does not have any laws requiring people to get rid of their fishing line and tackle safely. So we got a bird in here with a fishing hook caught in his wing that caused both bones to break and an infected, open wound. People don’t cover the caulking on the sidewalks, and we will get three sparrows from one sidewalk. Synthetic hair ties that are left out are also a problem because they can entangle and then strangle.

A pigeon with a broken wing, via Andrew Garn

If you could select one bird that epitomizes New York in either physique or a specific personality trait, which one would it be?

It’s the pigeon and their physique; they are fabulous flying machines. They’re sleek, elegant, and given the chance to bathe as much as they want, they are scrupulously clean. We just don’t provide enough fresh water for them. Pest control companies want to sell their services so they talk about pigeons. There are exceedingly few diseases that we can get from them, and every major health department in the United States has published a one page statement: “Pigeons pose no serious health risk to people.” They are also so smart. They know what’s up, what’s going on. In 2012 the New York Times had an article about how pigeons can do higher math. There’s another article about pigeons being taught to recognize cancer in x-ray films.

What does helping New York’s wild birds mean to you?

The bigger purpose is to change attitudes that people don’t think we have wildlife. There’s so much of it and if you look, you really will see it. In fact just walking down Broadway, if one looks up you will very often see two or three red-tailed hawks going around riding their thermals up.

+++

[This interview has been edited]

If you encounter an injured or sick wild bird, here is information on how to help >>

RELATED: