Stuyvesant Town goes green: How the 70-year-old complex is reinventing itself in a modern age

Photos courtesy of Stuyvesant Town

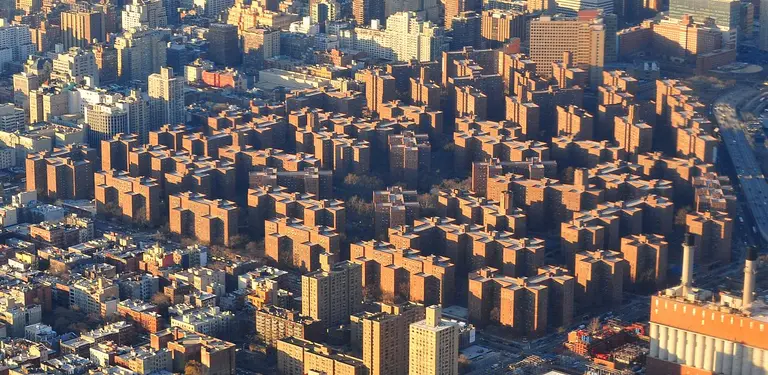

“Think of us as a 1947 Cadillac retrofitted with a Tesla engine,” says Marynia Kruk, Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village‘s Community Affairs Manager. Though the 80-acre residential complex’s 110 red brick, cruciform-shaped buildings were constructed 70 years ago this month, their imposing facades are hiding an intense network of systems that, since 2011, have allowed the development to reduce its on-site carbon emissions by 6.8 percent, equal to over 17 million pounds of coal saved. To put this in perspective, that’s roughly the same savings as 3,000 drivers deciding to bike or take the train for an entire year or planting a forest of 400,000 trees.

This massive sustainability push, along with new ownership (Blackstone Group and Canadian investment firm Ivanhoe Cambridge bought the complex for $5.3 billion in October 2015), updated amenities, and an affordable housing commitment, is driving Manhattan’s largest apartment complex into the future, and 6sqft recently got the inside scoop from CEO and General Manager Rick Hayduk and Tom Feeney, Vice President of Maintenance Operations, who is spearheading the green initiative.

The Gas House District in 1938 via Wiki Commons

Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village under construction

How it all began

It’s probably safe to say that Robert Moses didn’t have environmental responsibility in mind when designing and erecting Stuyvesant Town, but he was ahead of his time with respect to the inclusion of green space. In 1942, he began planning with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company the post-war housing project that would give affordable housing options to veterans and create the feeling of a country village within the city. Three years later, the $50 million project kicked off, replacing 18 city blocks that were formerly the Gas House District, stretching from 14th to 23rd Streets and 1st Avenue to Avenue C. When completed, the complex offered 11,250 apartments, their buildings connected by winding, landscaped pathways and anchored by a central lawn with a large fountain. In fact, only 25 percent of the site is actually occupied by buildings.

Photo via Wiki Commons

Affordable housing today

In 2006, Tishman Speyer and BlackRock Inc. made a record-breaking deal with MetLife to acquire the property for $5.4 billion. At the time, about 73 percent of the units were below-market rate, with one-bedrooms going for an average of $1,100/month. By mid-2014, after Tishman came under fire for trying to evict rent-regulated tenants, more than 2,000 of these apartments had been converted to market rate, with one-bedrooms starting at $2,900. As 6sqft previously reported, “After a high-profile lawsuit that demanded rent rebates be given to tenants (even those not in the rent-regulated units were being overcharged), the owners defaulted on $4.4 billion in debt and lost the complex to their creditors.”

When Blackstone Group and Ivanhoe Cambridge bought the complex for $5.3 billion in 2015, more than half of the 11,200 apartments were market rate. However, the new owners entered into an agreement with the city that said they would 4,500 units for middle-income families for the next 20 years with an additional 500 units set aside for low-income families. To do this, the city provided $225 million in funding, a $144 million low-interest loan through the Housing Development Corporation, and a waiver of $77 million in taxes.

In March 2016, the first affordable housing wait list opened for units ranging from $1,210/month studios for persons earning between $36,300 and $48,400 annually to $4,560/month five-bedrooms for families of five to 10 making between $136,800 and $210,870. The 15,000-name wait list was expected to be about two years long, but during that time, vacant units that had become de-regulated would be added to the pool instead of being rented out at market rate. And this past February, another lottery opened, this time for middle-income households earning between $84,150 and $149,490 annually, with apartments ranging from $2,805/month one-bedrooms to $3,366/month two-bedrooms.

Going green

In addition to committing to affordable housing, Blackstone Group and Ivanhoe Cambridge have set their sights on greening the complex. Though sustainability efforts first began in 2008, they’ve ramped up these efforts, in part to participate in the NYC Carbon Challenge, which supports the citywide goal of reducing carbon emissions 80 percent by the year 2050. They’re working closely with energy audit consultants Steven Winters Associates, who submit the information directly to the Mayor’s Office and work as an intermediary. To this end, Stuy Town has been awarded ENERGY STAR® certification for three years running, the first multifamily building in NYC to receive this distinction.

Here are the ways in which the team is meeting these goals:

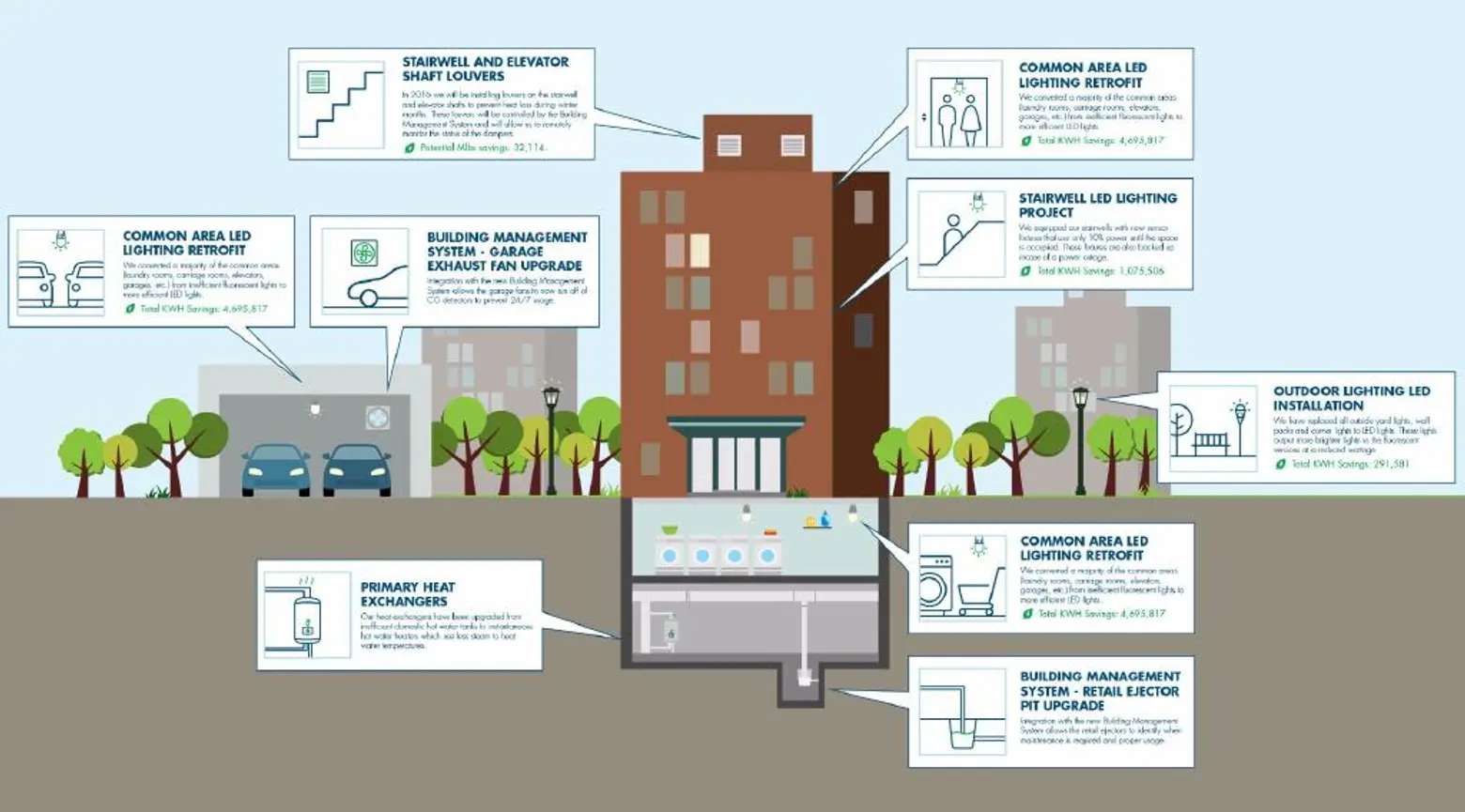

State-of the art, property-wide Building Management System (BMS)

The BMS, which Tom Feeney refers to as the development’s “1,000 eyes,” allows Stuy Town’s engineers to monitor and adjust heating, cooling, and garage exhaust 24/7, even from their personal homes. The increased accuracy has led to over 800,000 kWh in electric savings, the equivalent of 60 houses turning their electricity off for an entire year. It’s also a smart financial investment for the complex, as their yearly utility bills are around $35,000,000.

Lighting

Bi-level, LED, motion-activated lights were installed in the stairwells, where previously lights remained on at all times. Now, they remain on at 10 percent power when not in use, but even when they detect movement and are on at 100 percent, they’re consuming less power than traditional filament light bulbs. Complex-wide, the change from fluorescent bulbs to LED has resulted in six million KWH+ of annual electric savings.

Primary heat exchangers

This has saved Stuy Town between 15 and 20 percent on steam consumption for heating and hot water production. As with most multi-family developments, many complaints come from residents either feeling too hot or cold in their apartments. Since there was no way to give units individual control of their heating without ripping the buildings apart, they installed zone valves and put sensors in three apartments in every apartment line in the property, so that temperature can be continually monitored.

Stairwell and elevator-shaft louvers

Louvers were installed to close the openings at the top of stairwells and elevator shafts in order to prevent heat loss.

Garage VFD (variable frequency drives)

Garage exhaust fans are tied into a Carbon Monoxide detector, allowing them to run when only when needed instead of around the clock.

Cool roofs

The complex has a whopping 20 acres of rooftops, so it makes perfect sense why they decided to participate in NYC CoolRoofs, part of the overall carbon challenge. Flat, black asphalt rooftops can heat up to 190 degrees on an average summer day, but those treated with a specialized white coating can reduce internal building temperatures by up to 30 percent. And to put this in perspective, for just 2,500 square feet, roughly 1/348 of StuyTown’s roofage total, the city’s carbon footprint can be reduced by 1 ton of CO2.

Smart weather station

Officially called the ET-300-W, StuyTown’s smart weather station is used “to collect onsite weather data and help dictate irrigation levels based on real-time data.” It’s powered by solar cells in order to send the data to a nearby wireless controller, from which the Grounds & Landscaping Department can then determine how much water is needed for the complex’s 80 acres of soil.

A “tipping rain bucket” records onsite rain fall, showing when irrigation can be shut down and generating an “EvapoTranspiration calculation” that estimates how much moisture needs to be replenished from the previous day’s evaporation.

Recycling programs

In addition to having sorted bins in each building, StuyTown provides on-site shredding four times a year, textile drop-off service every Sunday at the green market, and a composting bin for each building that’s emptied three times a week, each time producing more than five tons of compost.

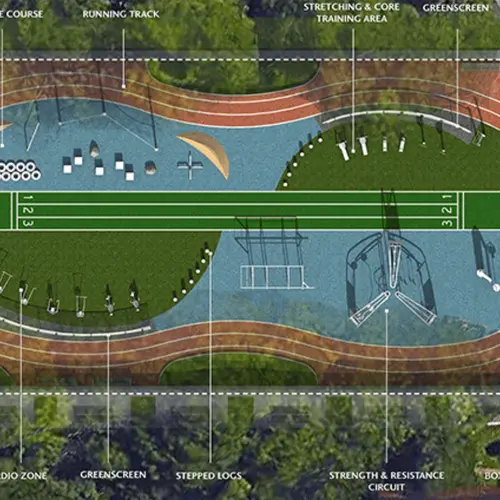

Outdoor amenities

Considering the amount of open space the complex has, it only makes sense to utilize these outdoor areas for amenities instead of using extra resources and materials to bring them indoors. In addition to dog runs, a weekly green market, five basketball courts, five paddle tennis courts, four bocce courts, two artificial turf playgrounds, and a volleyball court, StuyTown recently unveiled conceptual renderings for the Fitness Playground, a proposed conversion of an existing asphalt site into a park-like exercise area that includes:

- 1/12th of a mile walking and running loop

- 40-yard dash track

- Broad and vertical jumps

- Stationary cardio machines

- Upper body strength and resistance training tools

- Stretching, core training, and abdominal exercise benches

- Stepped logs with connection points for battle ropes

- Obstacle course with plyometric boxes, tires for agility training, and cargo nets

- Boxing corner

- Water filling station & lockers

Photo via Wiki Commons

Currently, in its 70th anniversary month, Stuyvesant Town continues to reinvent itself. As CEO and General Manager Rick Hayduk puts it, “a metaphor that we use frequently is the iceberg.” He explains, “Above the waterline, you have the red brick and green windows that everybody knows. But below the waterline, you have this incredibly sophisticated Rock Center-esque building management system and energy conservation. If you want responsible living in this area of New York it’s a great place to live.”

+++

All images courtesy of Stuyvesant Town unless other noted