The 1864 presidential election and the thwarted plot to burn New York City

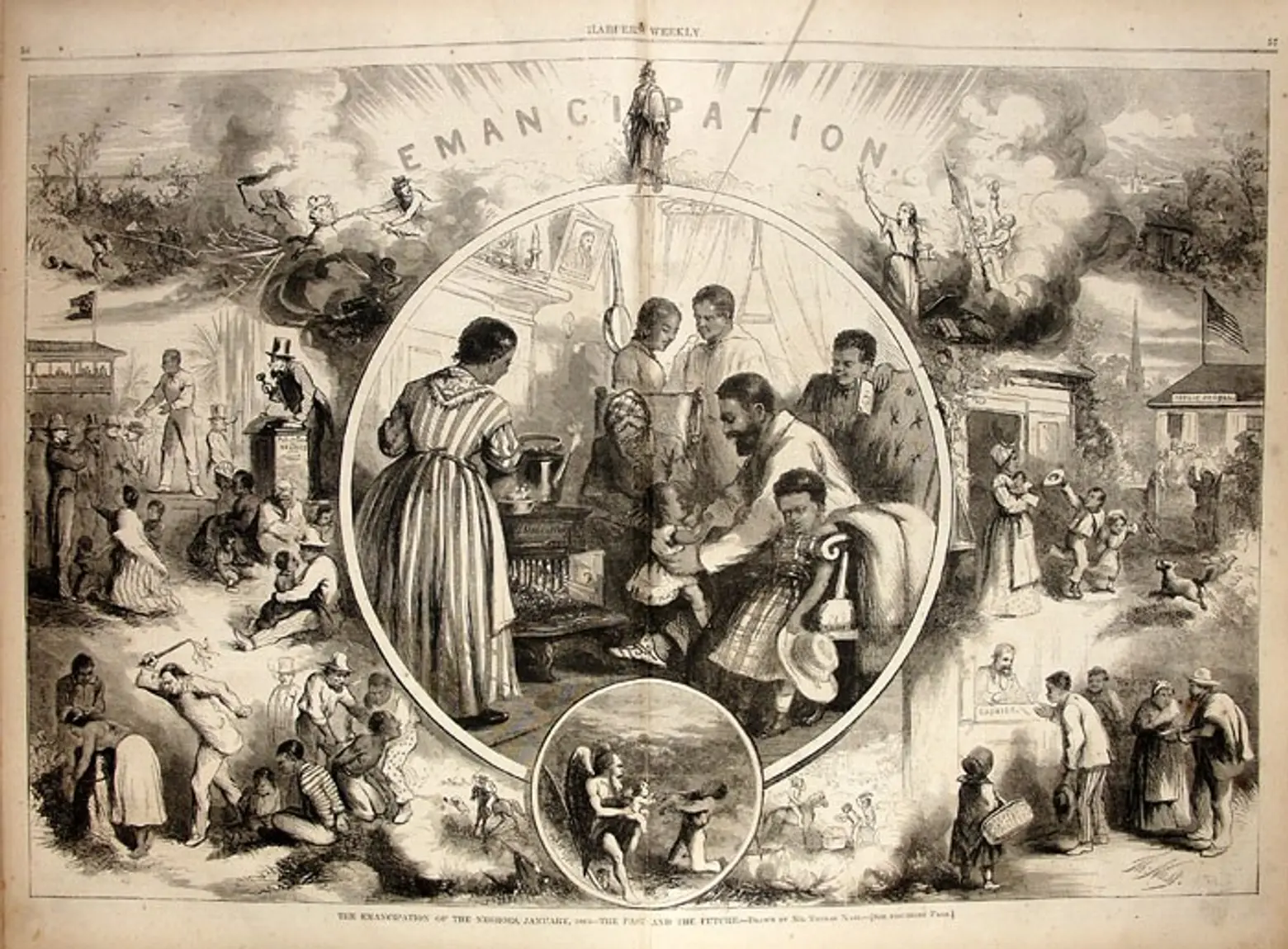

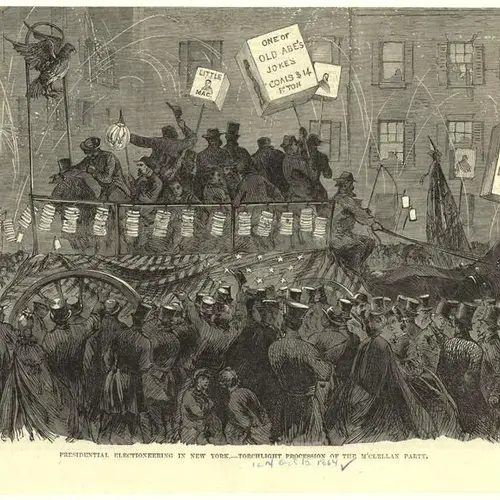

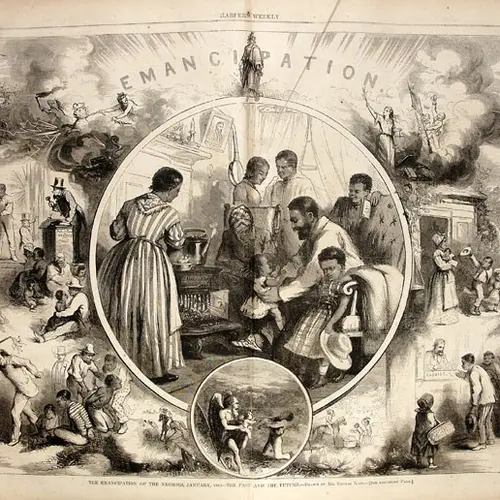

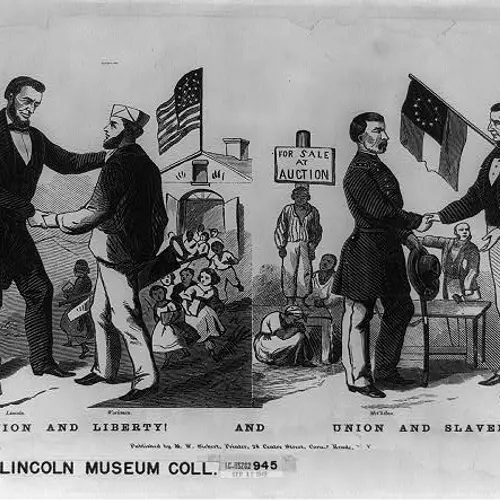

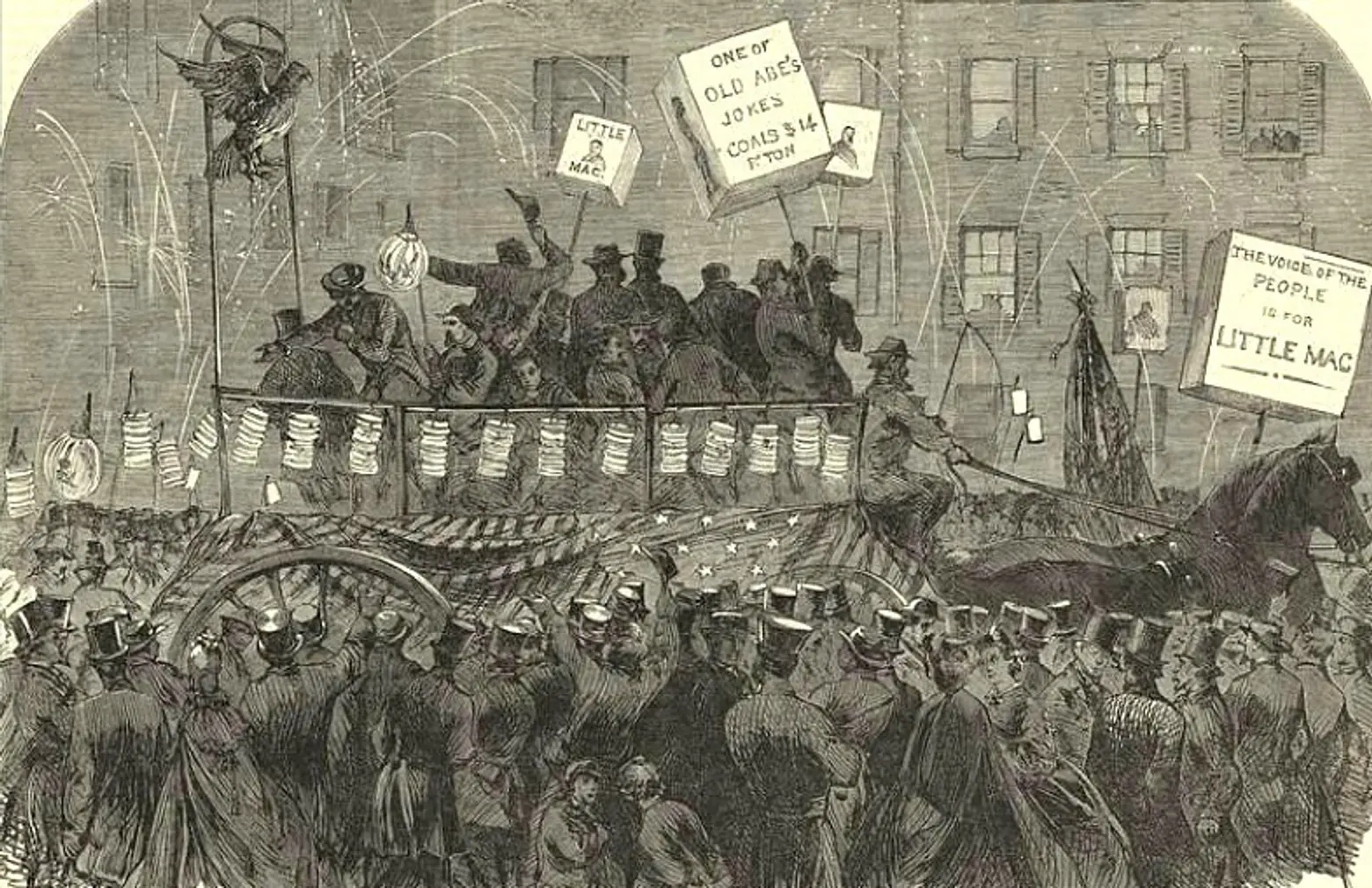

Presidential election of 1864. Political drawing by Thomas Nash

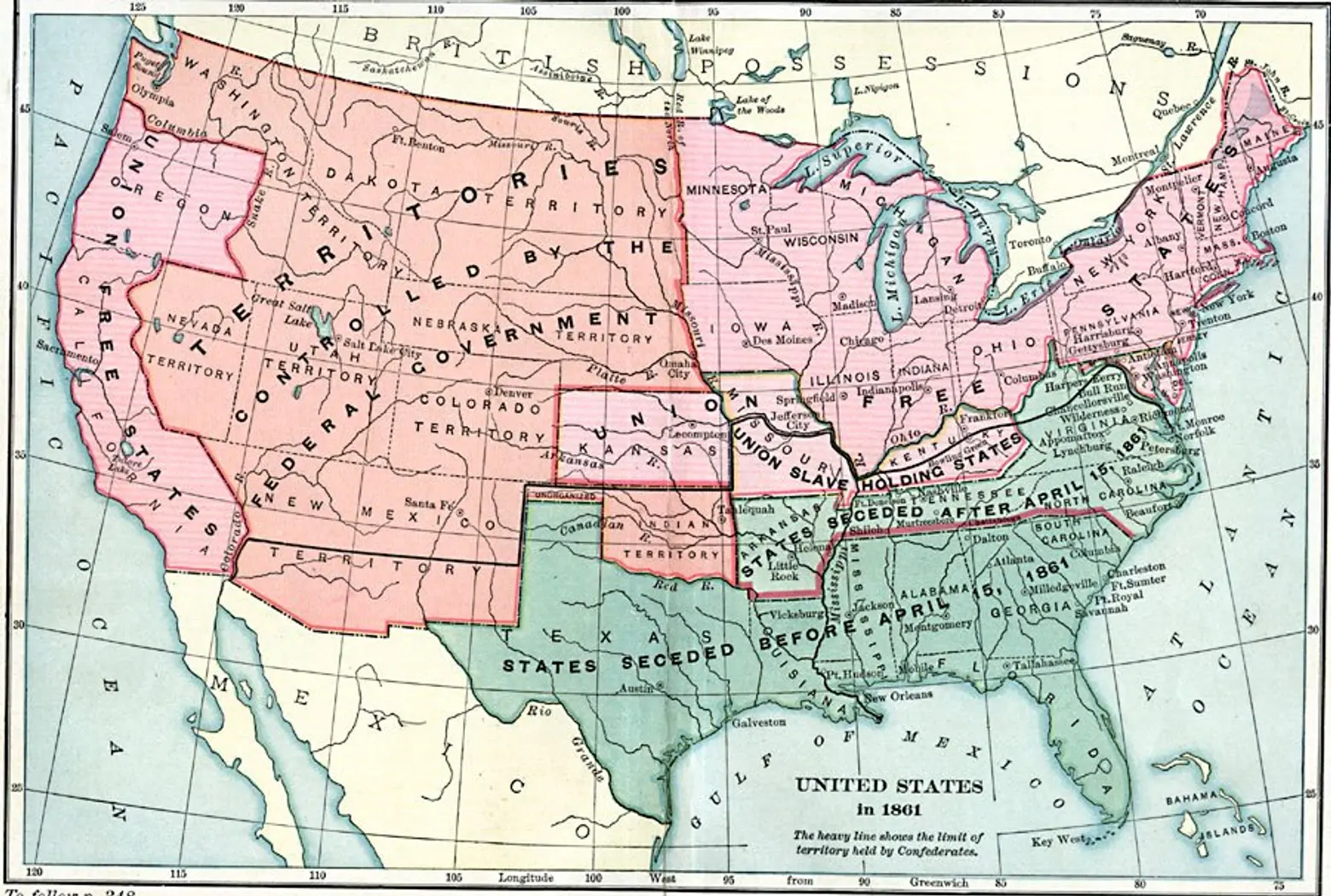

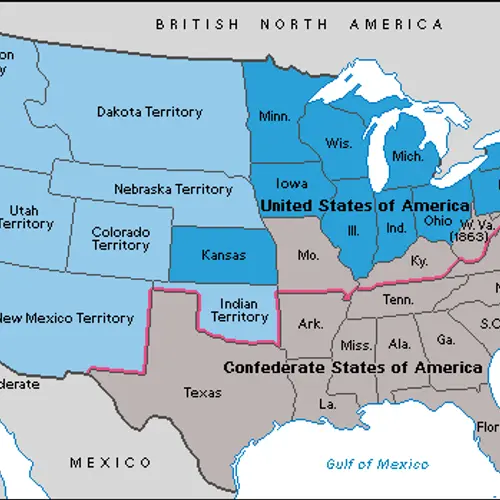

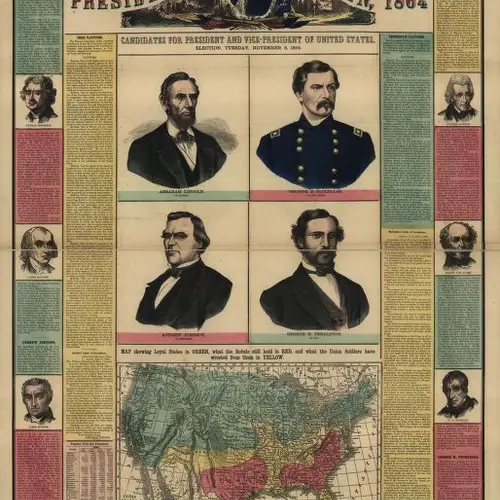

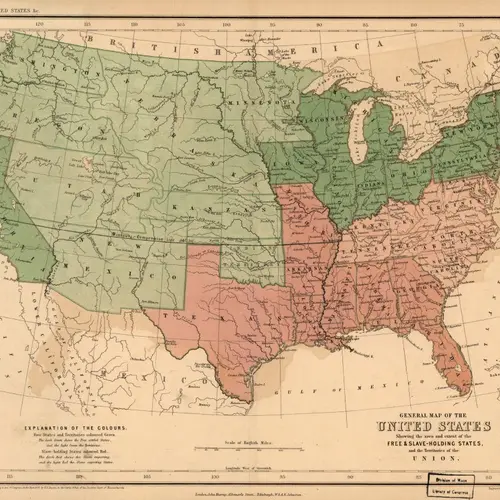

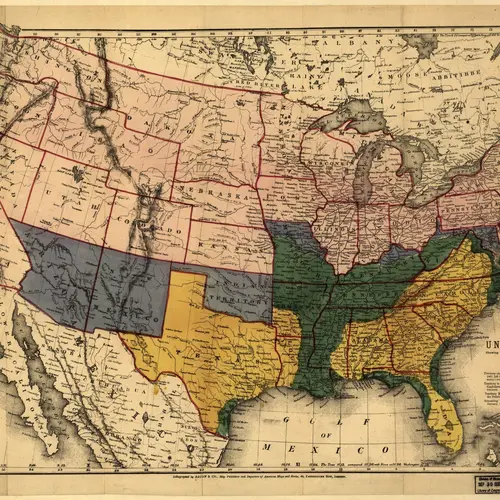

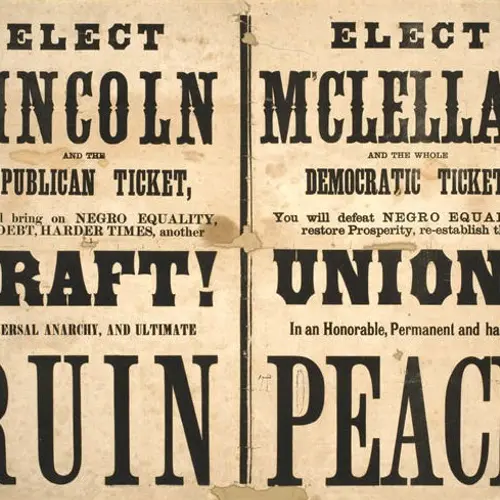

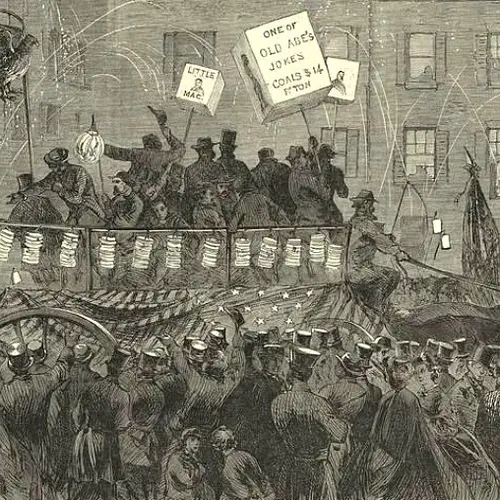

This election has been turbulent to say the least, erupting into contentious rhetoric, violence at rallies, and collective anxiety. But this isn’t the first time the U.S. has experienced such uproar from an election. In 1864, in the throws of the Civil War, incumbent Republican Abraham Lincoln was running for re-election against Democratic candidate George B. McClellan, his former top War general. Although both candidates wanted to bring the Civil War to an end, Lincoln wanted to also abolish slavery, while McClellan felt slavery was fundamental to economic stability and should be reinstated as a way to bring Confederate states back into the Union. Here in New York, this battle led to a plot to burn the city to the ground.

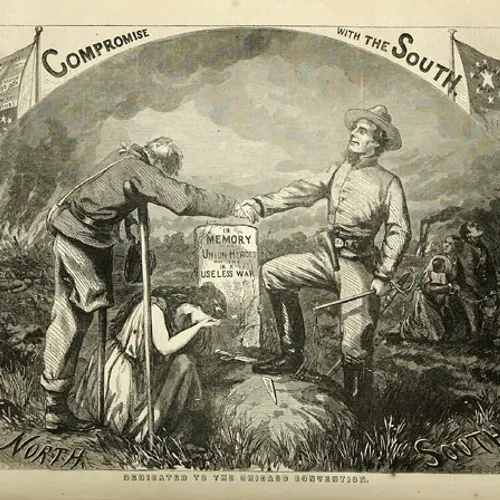

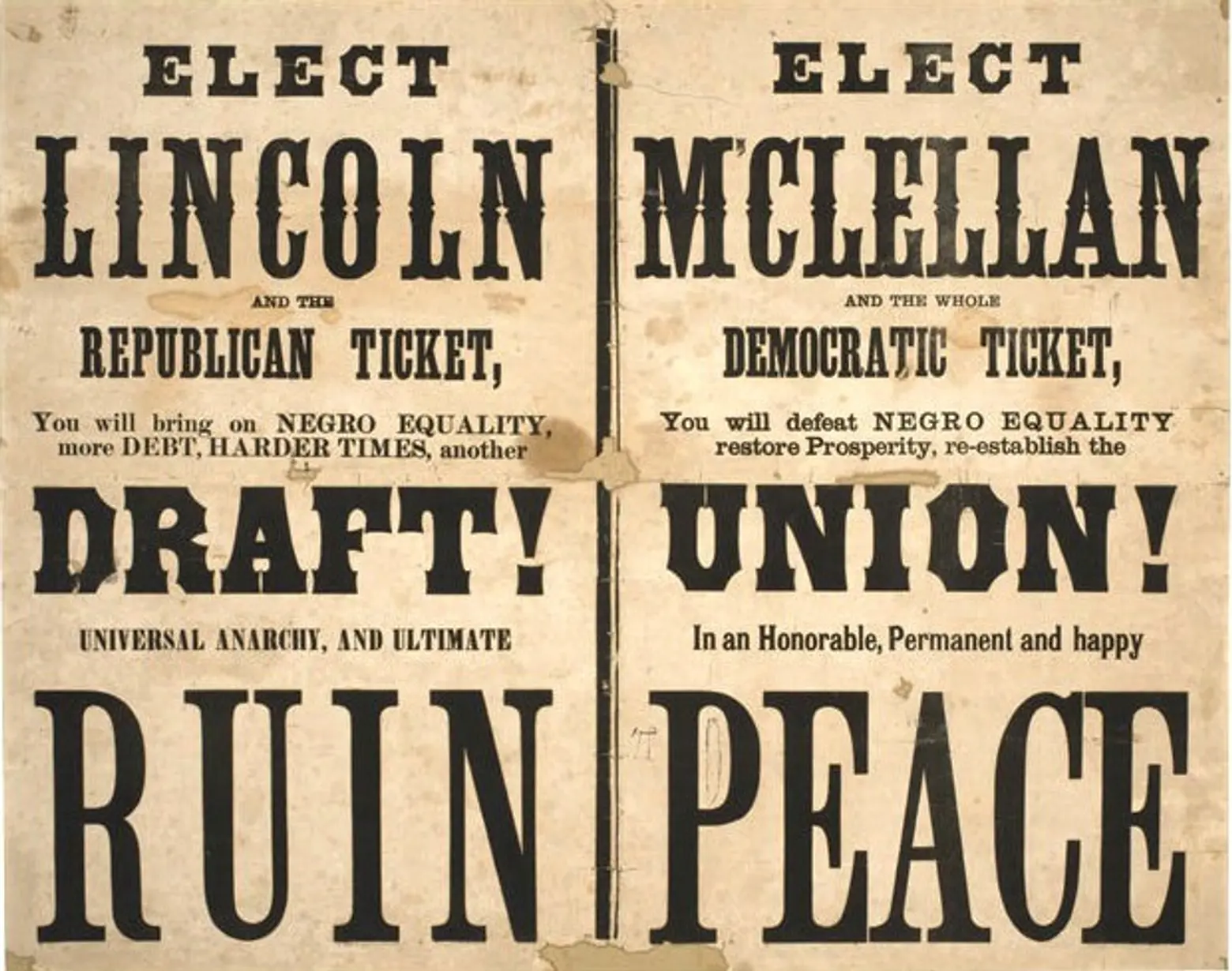

During the campaign, each side was adamant about where they stood regarding slavery and how they would reunite the Union. It appeared the majority was leaning toward ending the war even if it meant reinstating slavery. The south felt the north didn’t have the stamina to continue the war and were convinced they would give in and elect McClellan.

Presidential election campaign poster, 1864

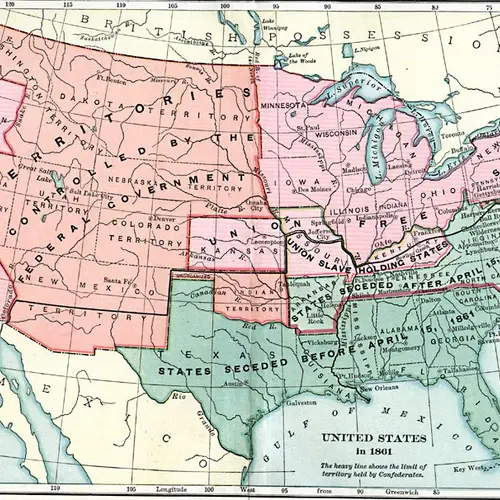

The Confederacy’s hopes of winning the War began to wain as they experienced a surge in battlefield losses, a Federal naval blockade, and international support from the likes of Britain and Italy for abolishing slavery. In an attempt to weaken the North, Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate government, devised a series of plots with the South’s Canadian-based Secret Service. Their network included hundreds of soldiers, agents and operatives who would help carry out their plans, the most ambitious of which was a plot was to burn New York City.

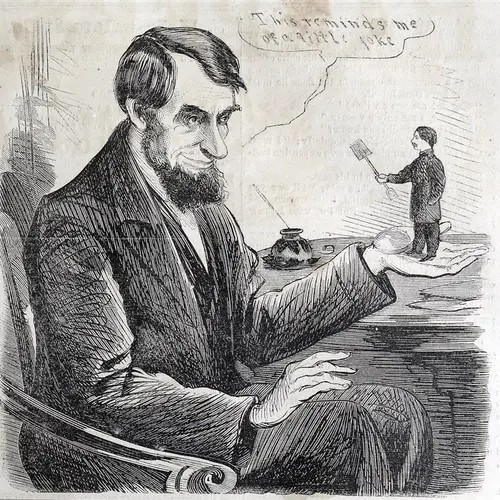

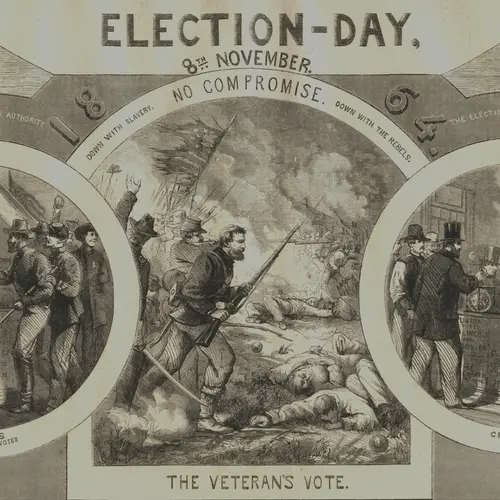

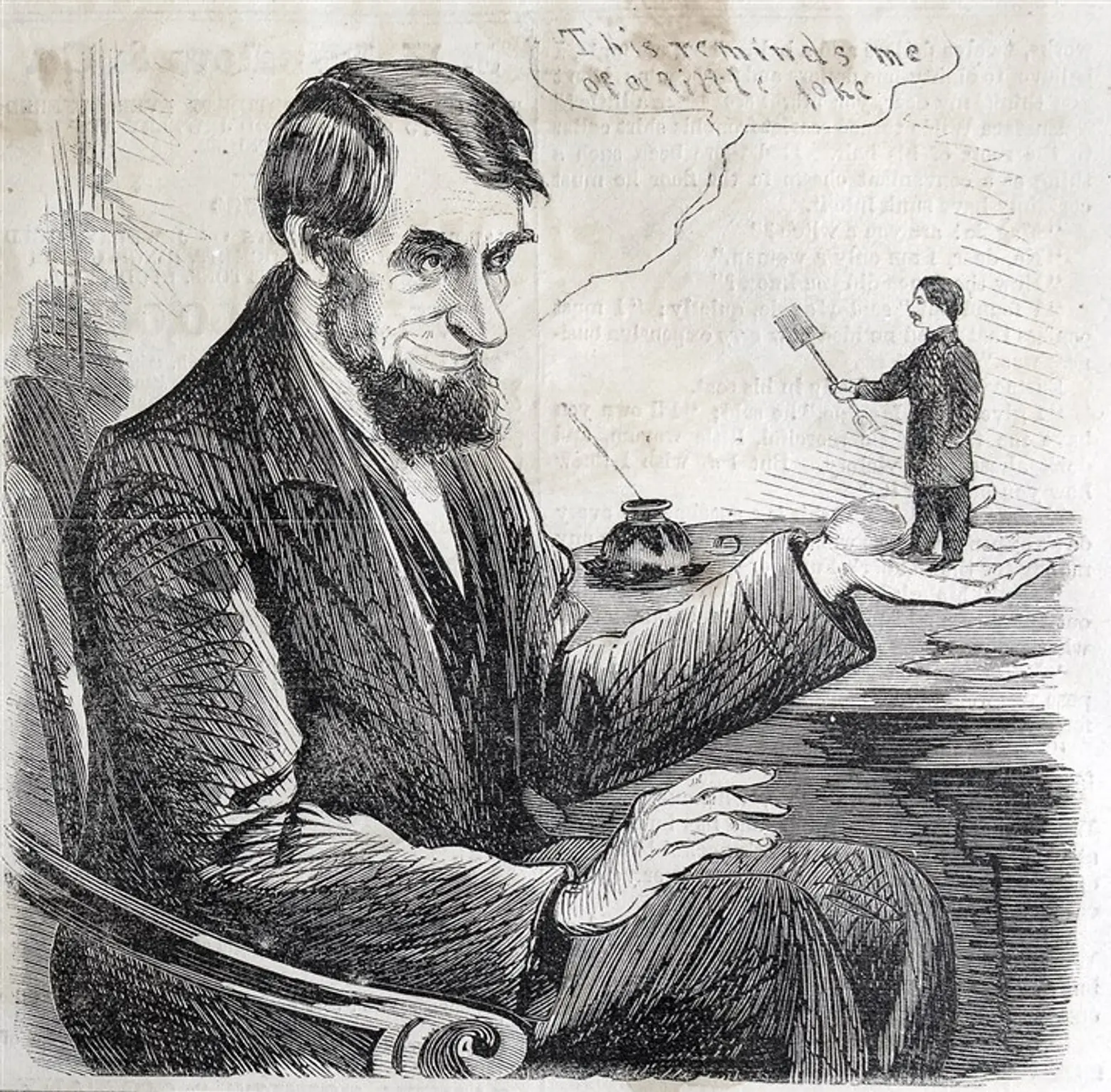

A cartoon of Lincoln and McClellan from the June 25, 1864 issue of Harper’s Weekly

A cartoon of Lincoln and McClellan from the June 25, 1864 issue of Harper’s Weekly

Hand-picked rebel operatives traveled from Canada to New York and Chicago to unite with northerners who supported the Confederate states. Rebels planned to seize each city’s treasury and arsenal and release Confederate prisoners of war. The plan initially involved setting several small fires to distract authorities, but combat officer Col. Robert Martin planned to burn New York to the ground.

According to the New York Times, Rebels contracted a retired druggist to make 144 four-ounce bottles of a combustible substance known as Greek fire. To do the greatest damage in the business district on Broadway they planned to set fires in the various hotels (after checking in using fake names) starting at 8pm, giving guests a chance to escape. Word of the organized revolts leaked and got back to Washington, which gave Secretary of State William H. Seward the chance to send a telegram to New York City’s mayor. Sent on November 2, 1864, it advised the Mayor of “a conspiracy on foot to set fire to the principal cities in the Northern States on the Day of the Presidential election.”

Thousands of federal troops marched into New York, establishing a military perimeter around the city that included gunboats stationed at various points surrounding Manhattan. The New York rebels were slowed, but were not done with their plan. They agreed to strike again in 10 days. Two members defected, but the remaining rebels would each be responsible for burning four hotels. Their list of targets included the Astor House, City Hotel, the Everett House, St. James Hotel, St. Nicholas Hotel, Belmont Hotel, Tammany Hall, and the United States Hotel.

Escaped prisoner Captain Kennedy strayed from the plan when he decided to stop for drinks at a local saloon after he set three hotels on fire. He then wandered in Barnum’s Museum and threw a bottle of Greek fire into the hallway, setting the building in flames. There were 2,500 people in the museum watching a play, but everyone escaped unharmed. The New York Times later observed, “The plan was excellently well conceived, and evidently prepared with great care, and had it been executed with one-half of the ability with which it had been drawn up, no human power could have saved this city from destruction.”

But enough fires were set in hotels to keep firemen busy for hours. As the Times described, “The next morning, all of New York City’s newspapers ran front-page accounts of the raid, as well as physical descriptions of the raiders, the fictitious names they had used to register and the promise that they would all be in custody by the end of the day.” All but one suspect made it home. Robert Cobb Kennedy was arrested by two detectives at a railway station outside Detroit and was ultimately hanged in New York harbor.

In the end, Lincoln won the election with a landslide of 212 electoral votes (though he only got 33 percent of NYC’s vote), but he never let the world forget that the Civil War involved an even larger issue. In his second inaugural address, he said “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds…”

RELATED: