The 18th-century Yellow Fever pandemic that led to NYC’s first Health Department

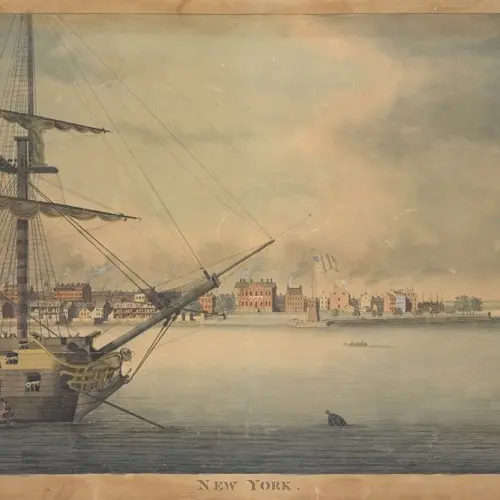

“New York, View From South, Man-of-war at Left,” 1793, via NYPL Digital Collections

A spot of hope amidst the chaos of our current moment is that we will come out stronger, safer, and more prepared than we were before. Historically, that has actually been the case. For example, New York’s 1795 Yellow Fever Pandemic led to the creation of the New York City Board of Health, which in turn became the Metropolitan Board of Health, then the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, which helps keep the city healthy to this day. Ahead, we take a closer look at this pandemic, which ebbed and flowed from 1793 to 1805, from quarantines to new hospitals to public data.

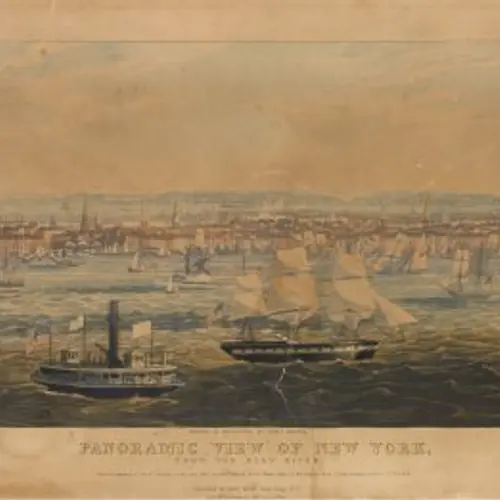

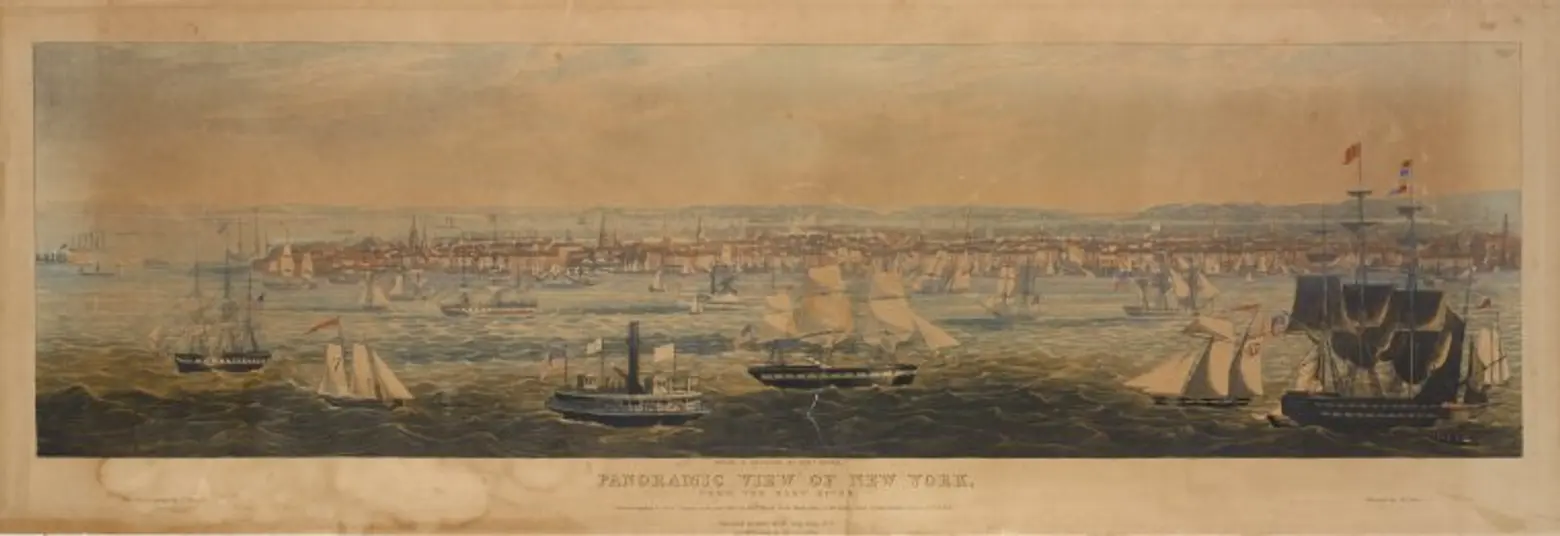

“Panoramic View of New York, From the East River,” via NYPL Digital Collections

It all began with a quarantine. In the summer of 1793, Philadelphia was hit with a Yellow Fever pandemic that felled approximately 5,000 people (about 10 percent of the city’s entire population). Faced with such numbers, a group of New York physicians formed a citizens’ Health Committee to quarantine all vessels arriving in New York from Philadelphia and prevent them from sailing passed Bedloe’s Island, where the Statue of Liberty now stands. The Health Committee also inspected incoming vessels, made arrangements to quarantine sick patients on Governors Island, and posted watchmen around the city’s wharves. Asked to cut off all communication with Philadelphia, New Yorkers were cautioned not to invite strangers into their homes. By the winter of 1793, the pandemic subsided in Philadelphia, and New York had been spared.

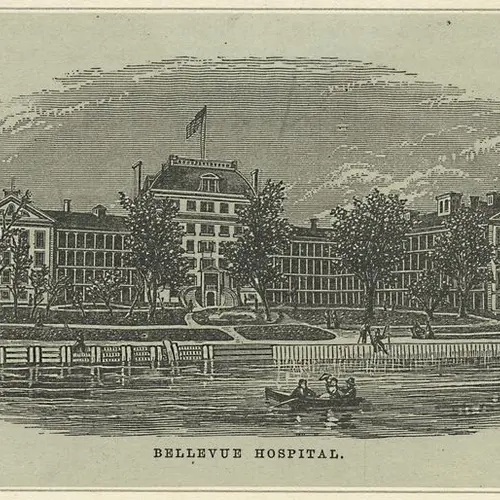

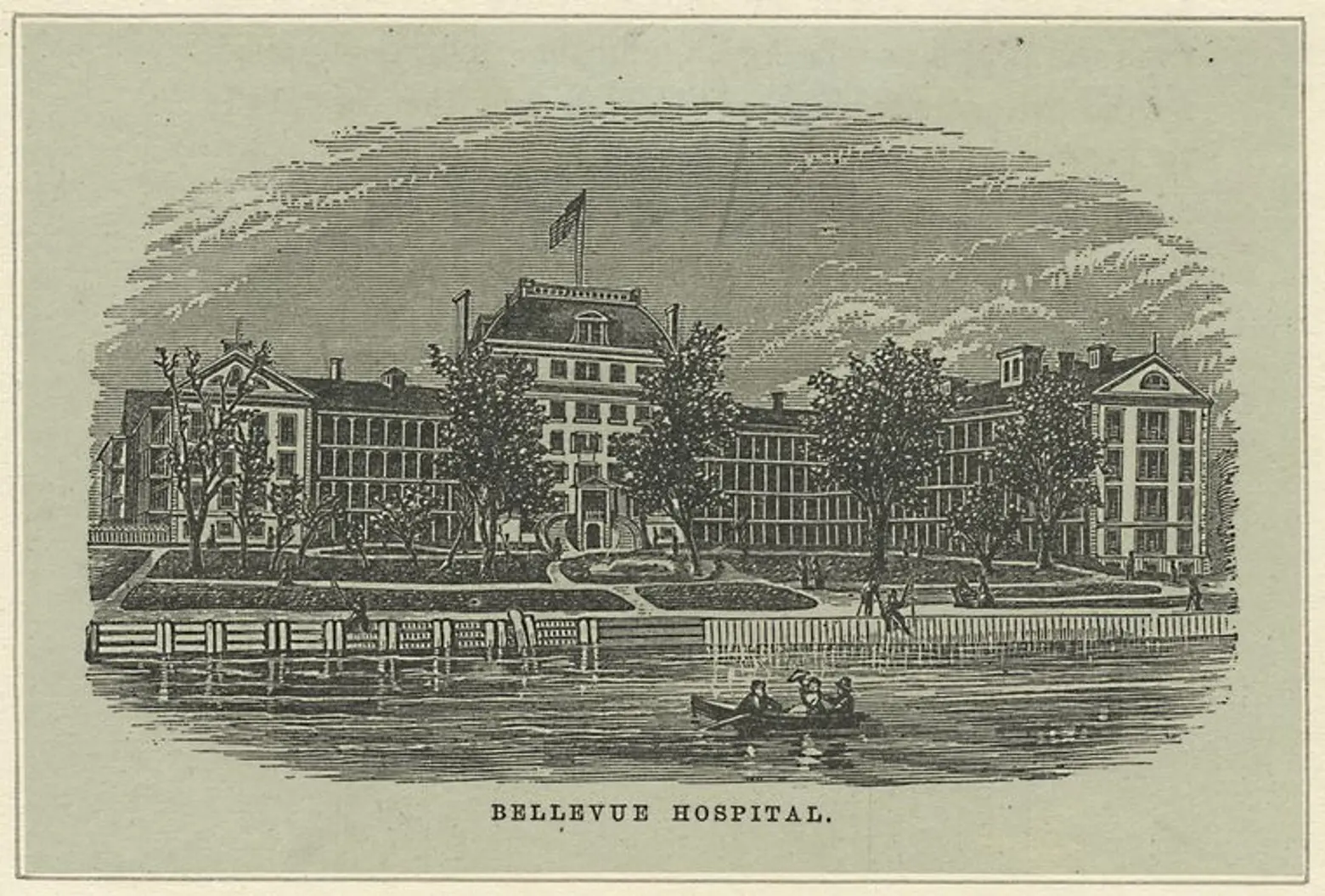

The following year, the city was more prepared. The Common Council purchased Brockholst Livingston’s four-acre estate on the East River, known as Belle Vue, and converted it into a quarantine hospital. Bellevue Hospital still stands on that site.

Bellevue, c. 19th Century, via NYPL Digital Collections

Because Yellow Fever is spread by mosquitos, the hot and muggy summer of 1795 was particularly suited to the disease, but New Yorkers at the time were unaware of how it spread. (One theory that held currency was that Yellow Fever was caused by drinking rotting coffee.)

When a ship docked in New York that July carrying Yellow Fever cases, New York merchants were unwilling to admit that it was a problem, since even the rumor of disease could hurt trading. In correspondence now housed at the New-York Historical Society, the merchant Isaac Hicks wrote that most merchants “are willing for [the ship] to go to New York in case the sickness does not stagnate the business so much that her cargo will not meet a sale.”

But news of the fever spread through New York, and wealthy citizens decamped to Greenwich Village, then a bucolic enclave north of the city. At the same time, the city’s poor, who were clustered on its fringes, closest to the wharves and the ships where the disease was most prevalent, were the most likely to be affected by the disease. By the end of the summer, 750 New Yorkers had been taken by Yellow Fever, out of a population of approximately 40,000.

In 1798, when Yellow Fever returned to New York, the situation was even direr, as about 2,000 people were carried away. In response, the Committee stepped in to aid the populous like never before. That summer, the Health Committee began doubling its inspection of perishable foods, cleaning jails, and expanding Bellevue; because the city’s economy was so disrupted, the Health Committee created provision centers to make food and supplies available to the poor. Soon, these centers were feeding 2,000 people per day. Temporary stores also sprang up to provide free rations.

By 1802, when Yellow Fever returned again, the great civic powerhouse John Pintard began collecting mortality statistics for Yellow Fever. He wrote that he was compiling the data in order to increase public knowledge so that one day the fever could become “more controllable and less mortal.” Two years later, Pintard was appointed the first official City Health Inspector. In that role, his statistics became official city documentation.

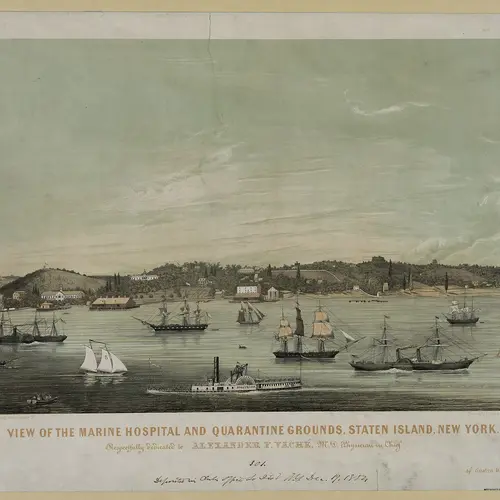

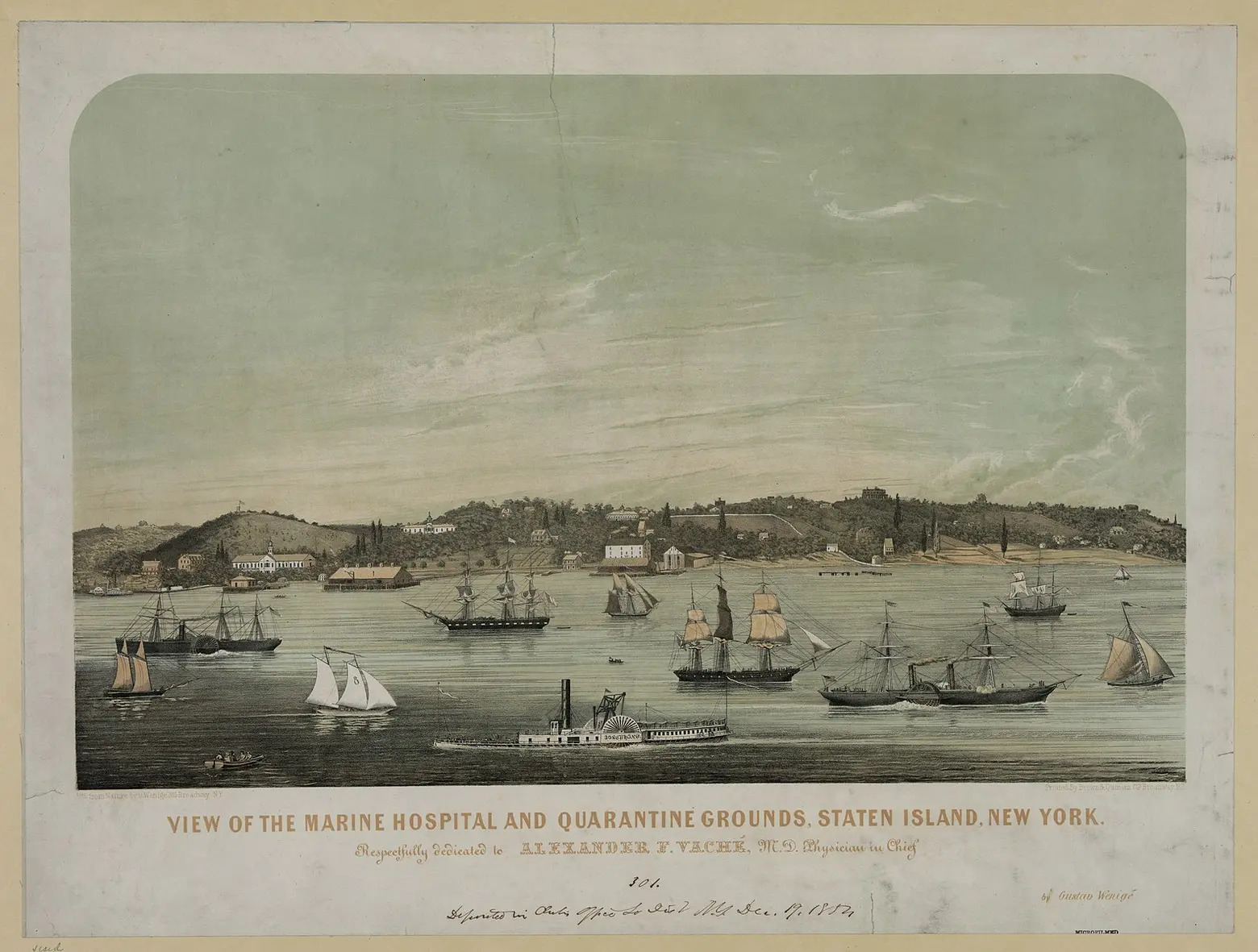

Photo via Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress

On January 17, 1805, the Common Council officially created the New York City Board of Health. The Board spent $25,000 fighting Yellow Fever in 1805, and swiftly removed patients from Manhattan to the Marine Hospital on Staten Island. The board also evacuated residents from affected areas and appointed night watchmen to guard the now-empty neighborhoods. Further, the Board built structures to house evacuated families. Since the Fever precipitated an economic crisis that put many New Yorkers out of work, the Board also provided food to people in need.

Strides that the Board made in civic preparedness, public education, accurate tallying, and municipal compassion helped reduce the number of 1805 Yellow Fever cases in New York City to 600, while the death toll came in at 262, a fraction of what it had been in 1798.

What preparedness, education, science, and compassion could do at the turn of the 19th Century, it can do today.

RELATED: