The Harlem Hellfighters: African-American New Yorkers were some of WWI’s most decorated soldiers

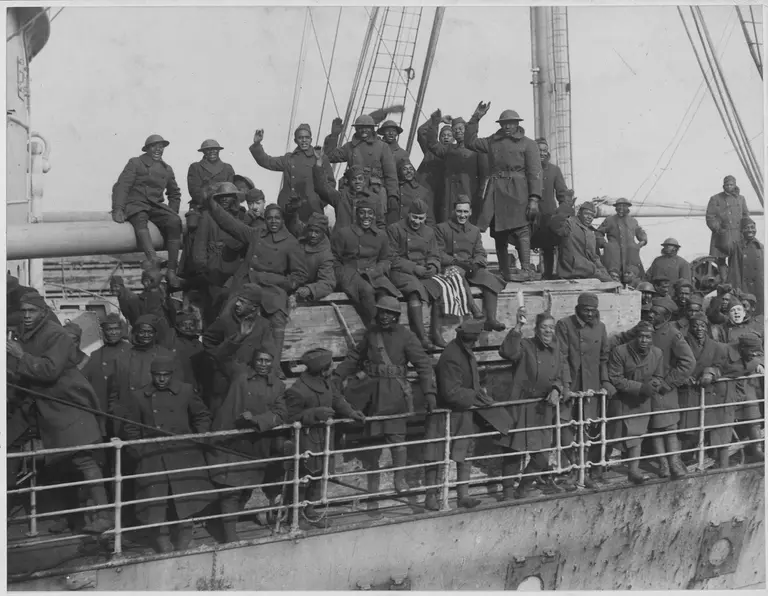

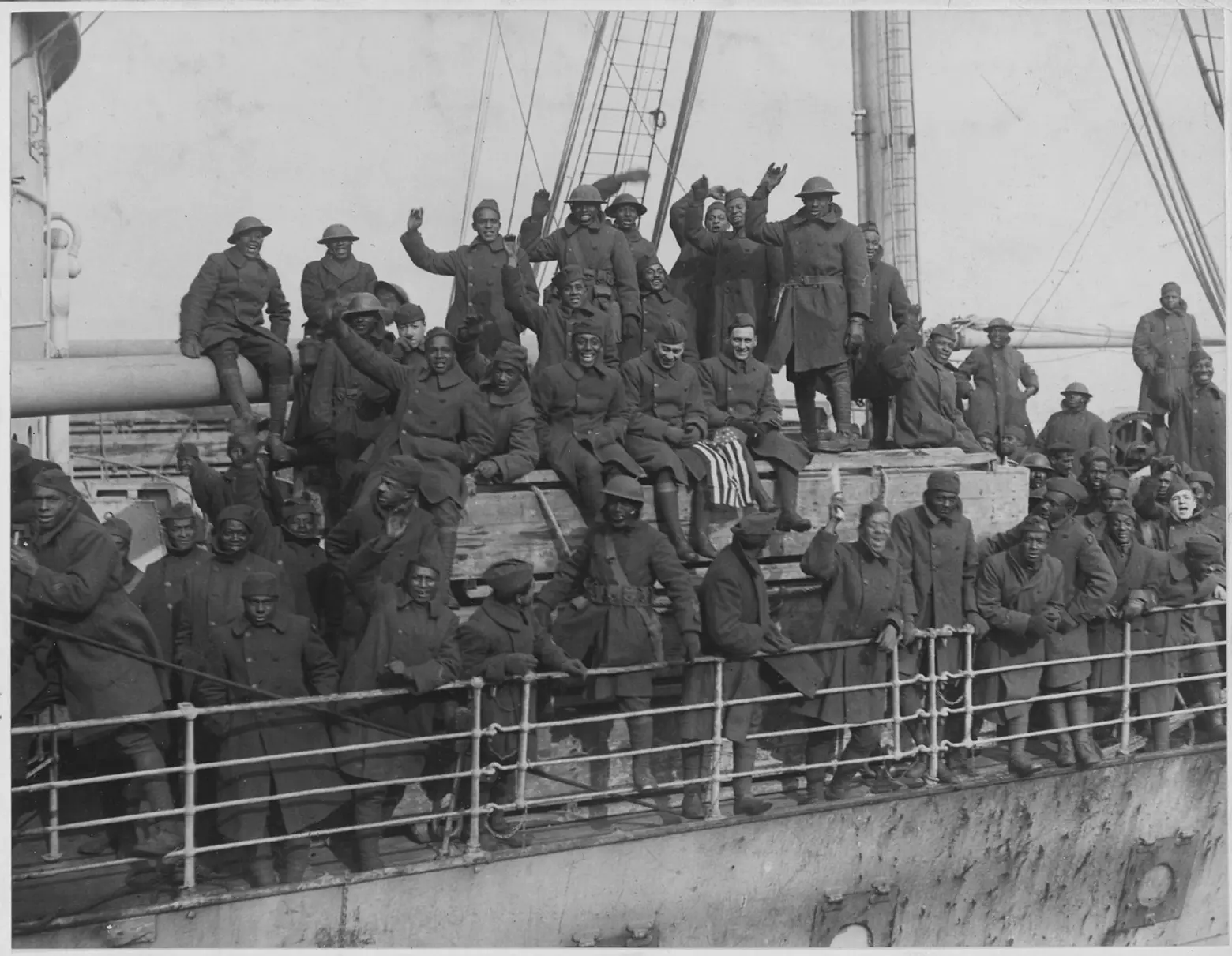

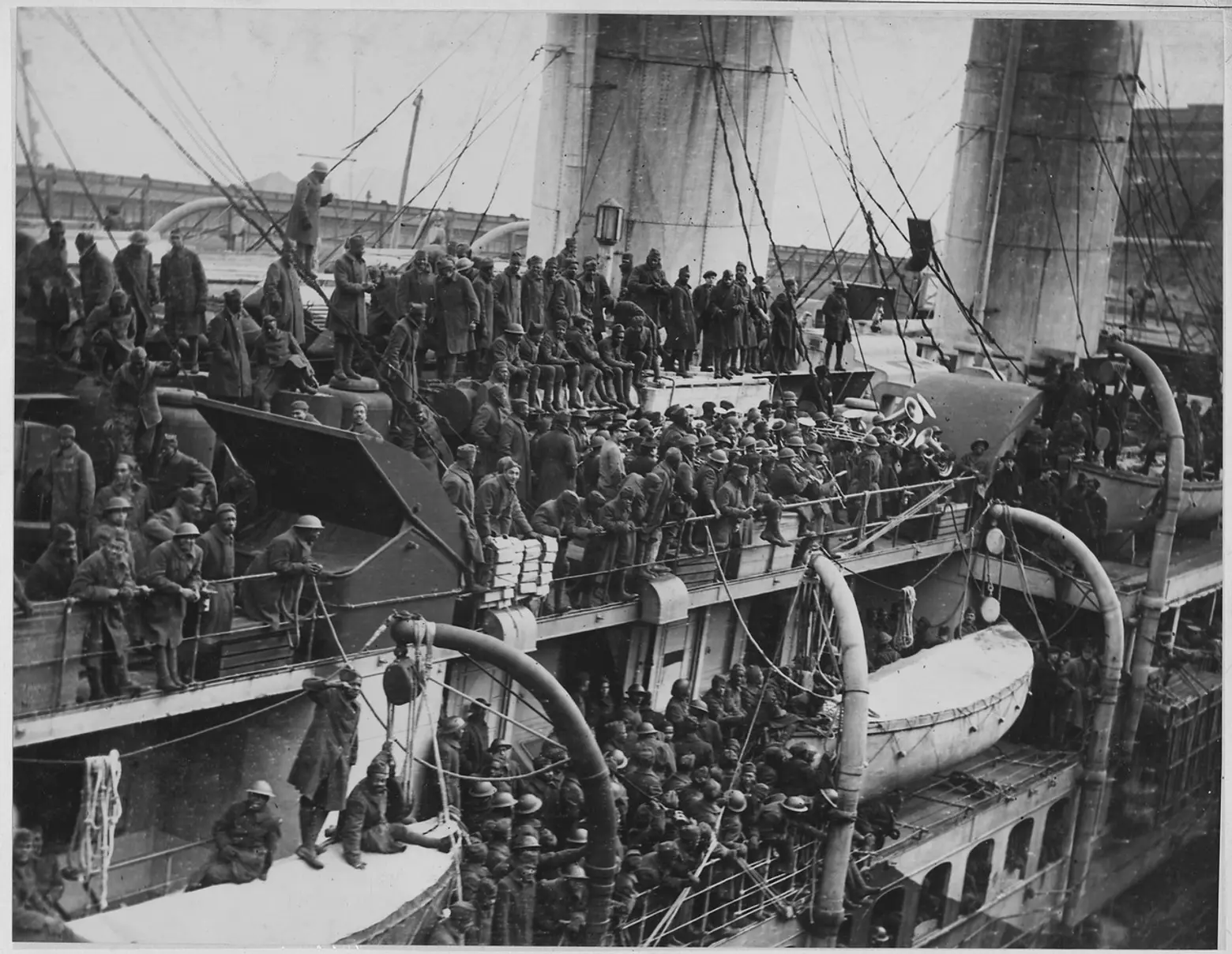

New York’s famous 369th (Old 15th) Infantry Regiment arrives home from France. From the National Archives via Wikimedia Commons

By the end of World War II, the Croix de Guerre, France’s highest military honor, would be awarded to the 369th Infantry Regiment. Better known as the Harlem Hellfighters, the regiment was an all-black American unit serving under French command in World War I, and they spent a stunning 191 days at the Front, more than any other American unit. In that time, they never lost a trench to the enemy or a man to capture. Instead, they earned the respect of both allies and enemies, helped introduce Jazz to France, and returned home to a grateful city where hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers turned out to welcome home 3,000 Hellfighter heroes in a victory parade that stretched from 23rd Street and 5th Avenue to 145th Street and Lenox.

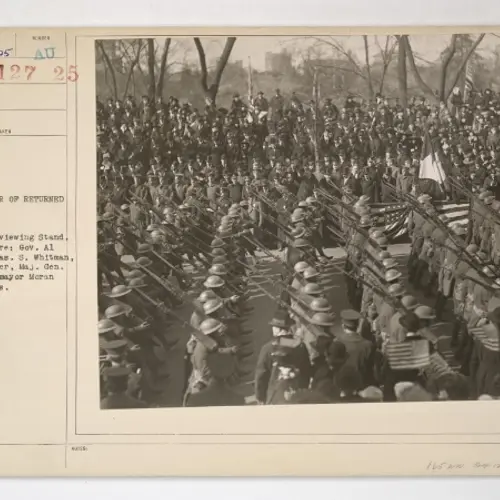

Victory Parade for the 369th marches up Fifth Avenue, February 1919, seen here at 42nd Street. From the National Archives via Wikimedia Commons (cropped)

Victory Parade for the 369th marches up Fifth Avenue, February 1919, seen here at 42nd Street. From the National Archives via Wikimedia Commons (cropped)

The deluge of celebration and weeping that greeted the returning Hellfighters when the parade made its way to Harlem was particularly impassioned since 70 percent of the regiment called Harlem home. But just as moving was the fact that the parade was the first such event following World Word II, for black or white soldiers, and the whole city was jubilant.

Harlem school children and other well-wishers gather along the victory parade route to greet the returning Hellfighters, from the National Archives via Wikimedia Commons

In a three-page spread covering the parade, the New York Tribune wrote, “Never have white Americans accorded so heartfelt and hearty a reception to a contingent of their black countrymen.” The paper observed, “In every line, proud chests expanded beneath the metals valor had won. The impassioned cheering of the crowds massed along the way drowned the blaring cadence of their former jazz band. The old 15th was on parade, and New York turned out to tender its dark-skinned heroes a New York welcome.”

Another view of the victory parade. From the National Archives via Wikimedia Commons

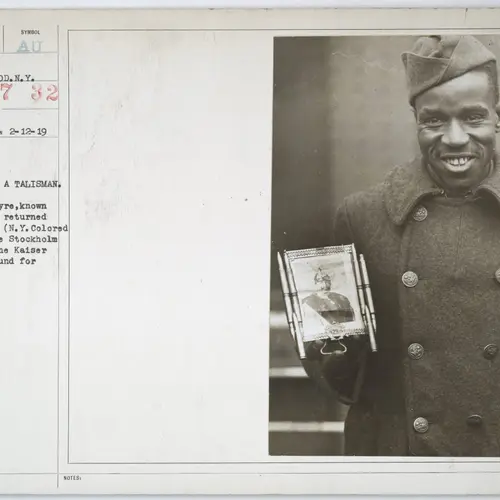

But that welcome stood in stark contrast to the Hellfighters’ experience in the City’s 1917 Farewell Parade. At the time, the unit was known as the 15th New York (Colored) Regiment of the state’s National Guard. It was part of the US Army’s “Rainbow Division,” a cadre of 27,000 troops from around the nation mustered in when the United States entered the war. Most of the Rainbow Division shipped off to Europe in August 1917. The Hellfighters wouldn’t arrive in France until late December of year. They had not been allowed to march off to war with the rest of the Rainbow Division, or to participate in the city’s farewell parade, because, they were told, “black is not a color of the rainbow.”

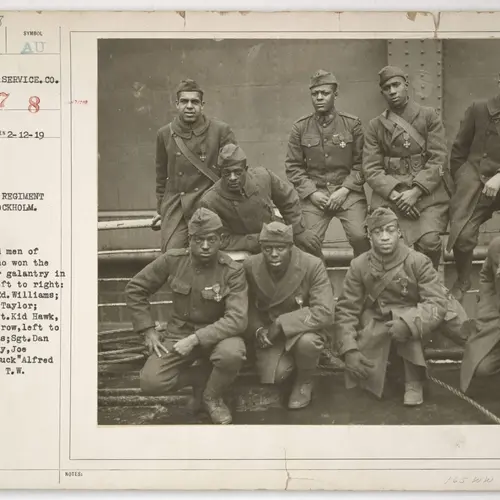

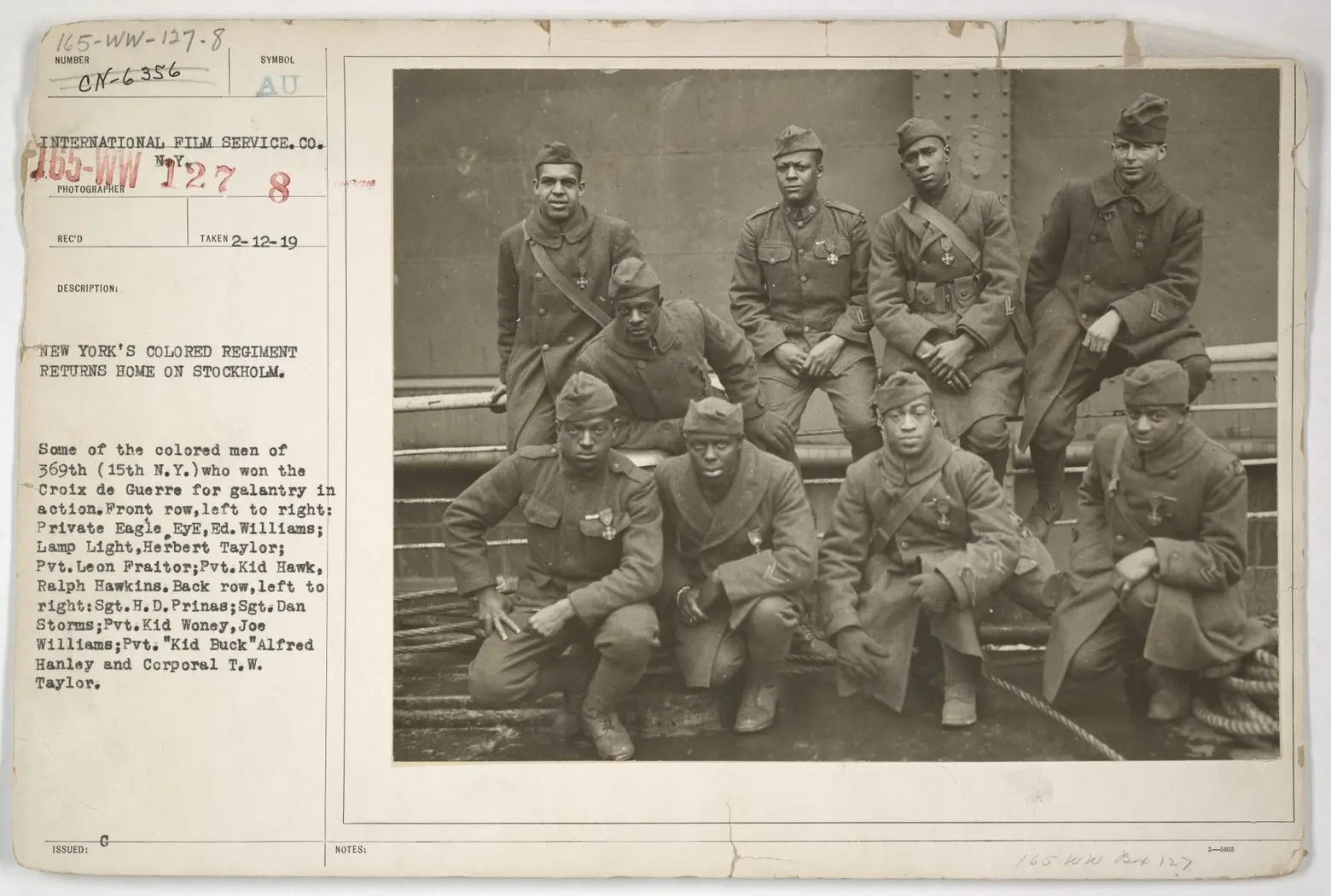

Each soldier in this group of decorated Hellfighters earned the Croix de Guerre, for gallantry in action. Via the National Archives

Despite the virulent racism and entrenched discrimination they faced, 2.3 million black Americans registered for the draft during WWI, and 375,000 served, including the 2,000 who volunteered for the Harlem Hellfighters. At the time, many African Americans saw military service as an opportunity for “Double Victory,” both at home and abroad, believing that demonstrations of wartime valor would help further the cause of Civil Rights.

Following years of advocacy by civic leaders in Harlem, in 1916, Governor Charles Whitman established New York’s 15th, the first all-black unit in New York’s National Guard. The unit was a prestigious post in Harlem: “To be somebody, you had to belong to the 15th Infantry,” remembered Arthur P. Davis, of Harlem, who served with the unit.

Lt. James Reese “Big Jim” Europe (front left) and the 369th Infantry’s Regimental Band. From the National Archives via Wikimedia Commons.

The Hellfighters marched under the command of a white officer named William Hayward, a former Colonel in the Nebraska National Guard. Hayward hired both black and white officers and recruited the jazz musician Lt. James “Big Jim” Reese Europe as the 15th’s regimental bandleader.

In the courtyard of a Paris hospital for the American wounded, Lt. James R. Europe and his band entertain the patients with real American jazz. From Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons.

During the 1910s, Europe was one of the leading jazz musicians in Harlem. He created the Clef Club, a local society for Black musicians that went on to play the first jazz show at Carnegie Hall. Once he was overseas, Europe put together a band of about 40 men who would perform for British, French, and American troops, as well as locals in France. When Jim Europe led his men off their troopship at Brest, on the coast of Brittany, he struck up a ragtime rendition of the Marseilles that thrilled and astonished the Frenchmen crowded on the docks. It’s said that their later performance in the French city of Nantes was the first jazz concert in Europe.

In civilian life, many of the recruits worked as porters, butlers, hotel doormen, and elevator operators. As soldiers in the segregated United States Army, they were slated for grunt work. For the first three months of their service in France, the Hellfighers shoveled dams, laid rail lines, and built hospitals; they were issued inferior uniforms and weapons. Despite such discrimination, the newly federalized 369th Infantry Regiment returned from France one of the most decorated and celebrated regiments to serve across all Allied forces.

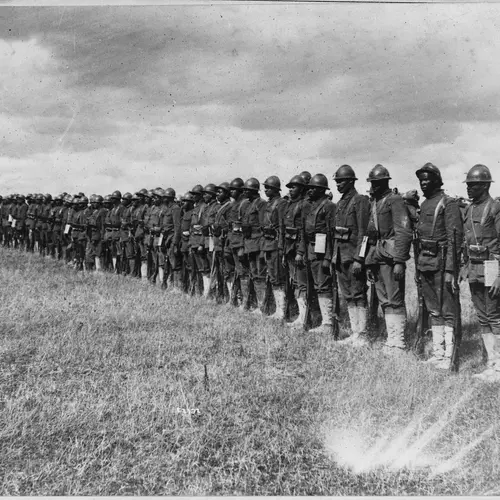

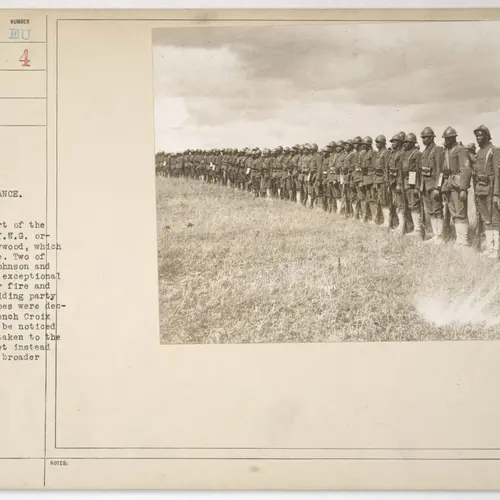

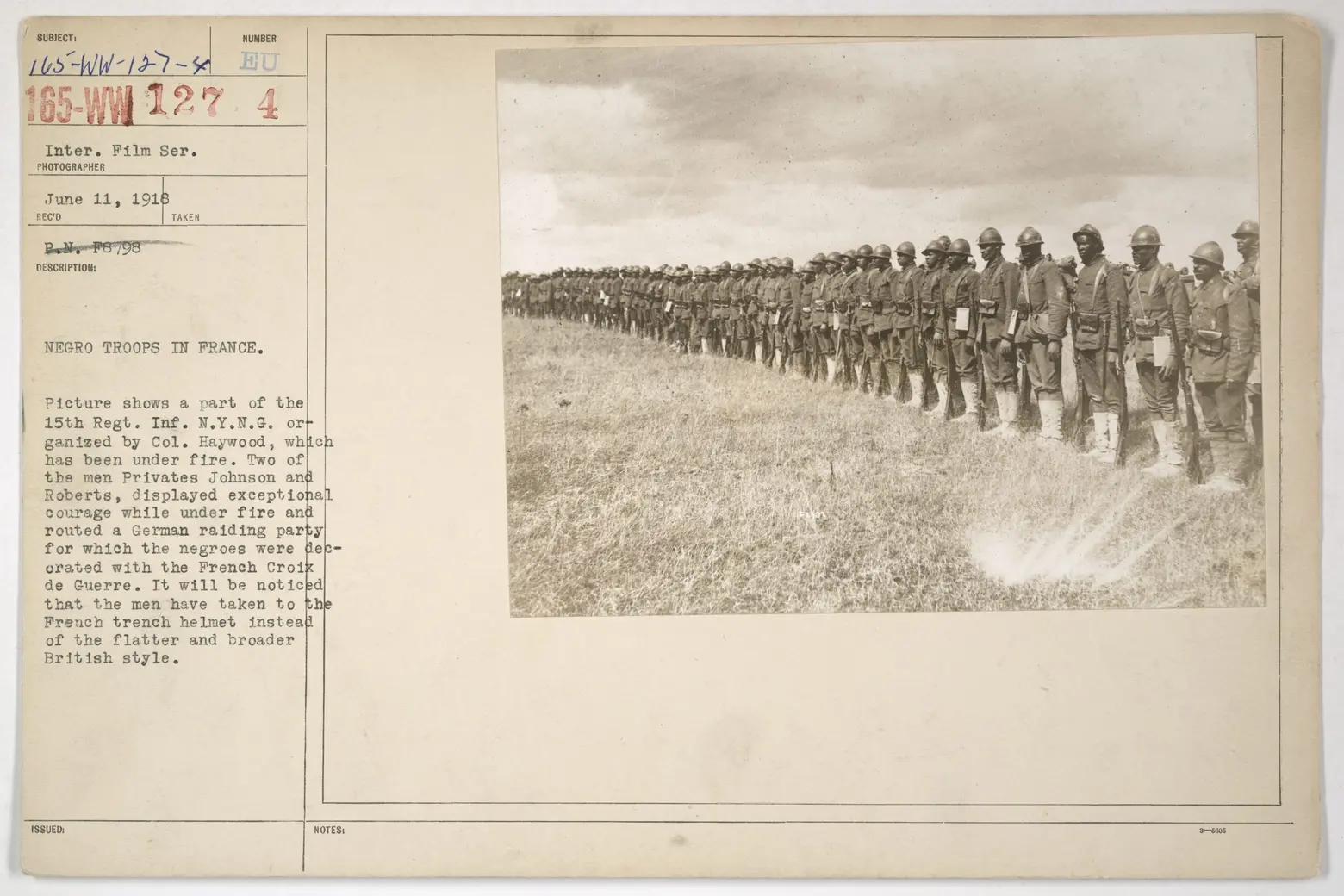

Members of the 369th stand in formation in France. They wear French helmets. Via the National Archives

On March 10, 1918, General John Pershing, head of the American Expeditionary Force, reassigned the 369th from the US Army Services of Supply to the French Army, where they would serve as reinforcements to the beleaguered French divisions. For Pershing, the move was politically expedient: The French had been asking for reinforcements and reassigning the African American unit ensured that the United States Army would remain starkly segregated.

After three weeks of training alongside French troops, the 369th entered the trenches on April 15, 1918, more than a month before soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force fought their first major battle. The Hellfighters fought valiantly at battles including Belleau Wood, Chateau-Thiery, and the Second Battle of the Marne. And fighting longer than any other American servicemen, they also sustained heavy casualties, with nearly 1,500 soldiers killed or wounded.

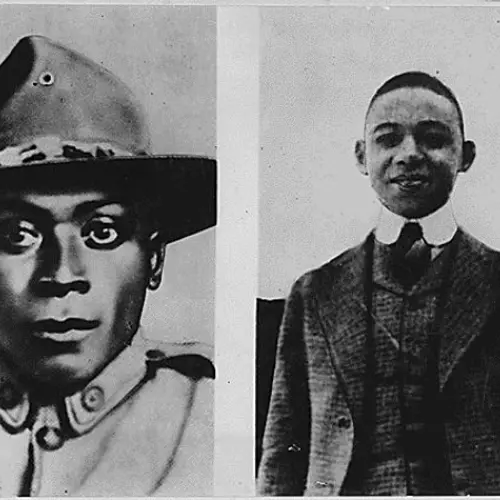

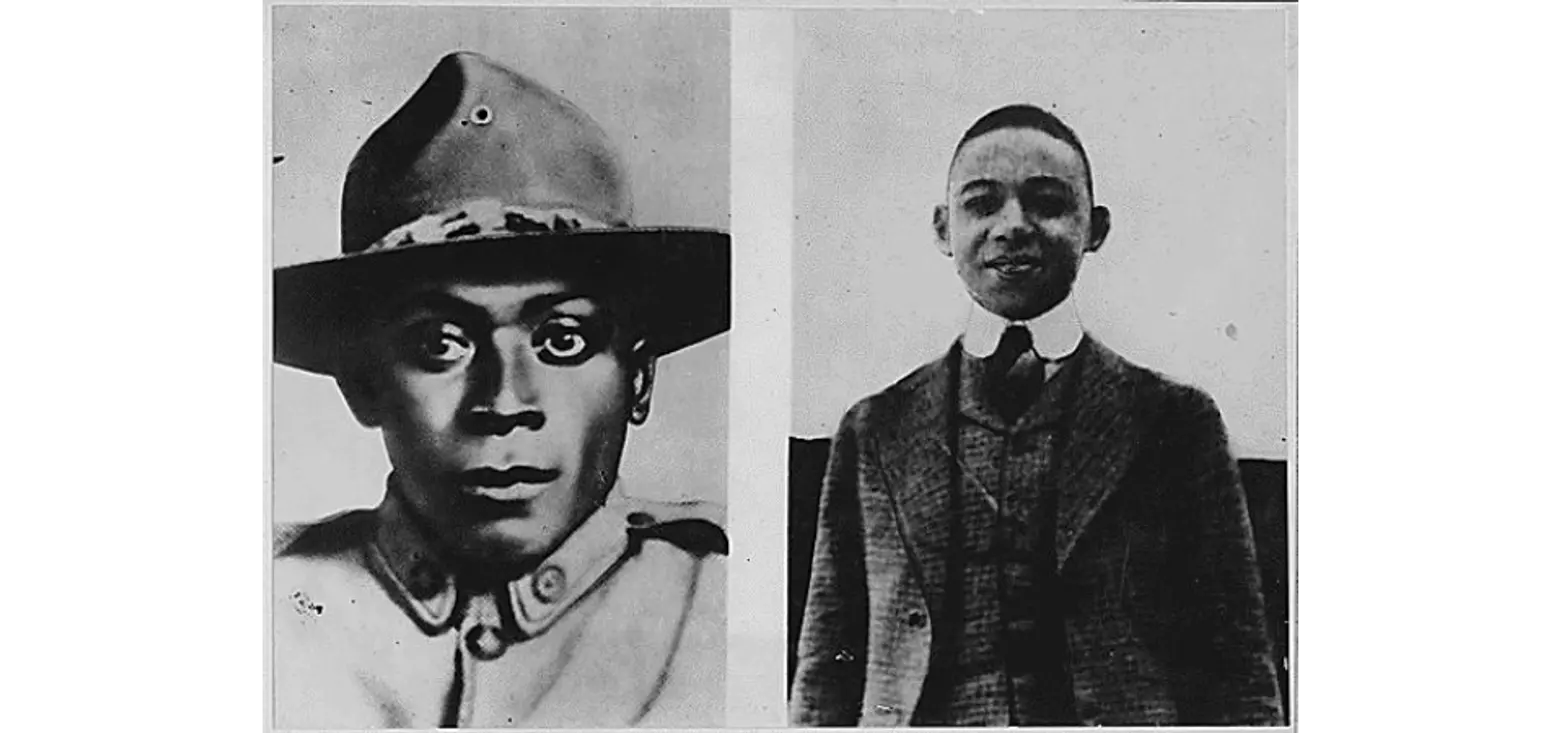

Henry Johnson (left) and Pvt. Needham Roberts. They were the first Americans ever awarded the Croix de Guerre. From the National Archives via Wikimedia Commons.

In the earliest hours of May 15, 1918, Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts were keeping guard over a frontline trench in France’s Argonne Forest, about 115 miles east of Paris. Suddenly, two-dozen German soldiers charged out of the pitch-black no-man’s-land. Despite being stabbed 21 times and shot at least twice, Johnson killed four German soldiers, repelled the other 20, and saved his injured comrade Roberts from capture, using little more than a nine-inch bolo knife. Days later, the French Army stood at attention as Johnson and Roberts became the first Americans ever awarded the Croix de Guerre. Johnson’s metal included a Golden Palm, for extraordinary valor.

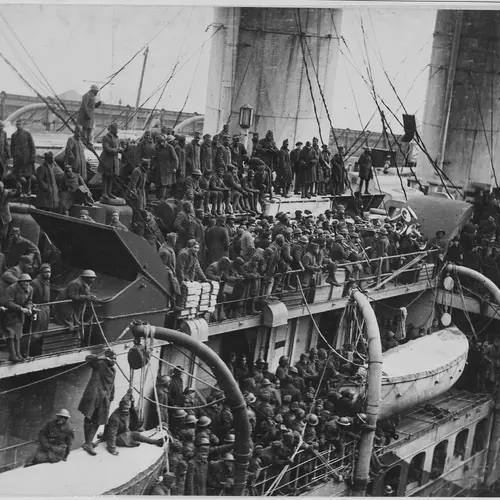

The French liner La France arrives home with the Harlem Hellfighters. From the National Archives via Wikimedia Commons.

At first, the Regiment referred to itself as the “Black Rattlers,” owing to their rattlesnake insignia. Their French comrades called the soldiers “Men of Bronze,” and their “Hellfighters” moniker came courtesy of the Germans they defeated, who recognized their remarkable bravery and tenacity.

Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work (left) stands with distinguished guests during a ceremony inducting Medal of Honor recipients Army Sgt. Henry Johnson and Army Sgt. William Shemin into the Pentagon Hall of Heroes June 3, 2015. DoD photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Sean Hurt/released. Via Wikimedia Commons.

It would take nearly a century for the United States government to tender the Hellfighters that same recognition. In 2015, President Obama posthumously awarded Sgt. Henry Johnson the Medal of Honor. Ninety-Seven years after Johnson became the first American to earn France’s highest military decoration, he was awarded the same designation in his own country.

RELATED:

- The story behind Harlem’s trailblazing Harriet Tubman sculpture

- A mecca of African American history and culture, Central Harlem is designated a historic district

- 10 secrets of Harlem’s Apollo Theater: From burlesque beginnings to the ‘Godfather of Soul’

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.