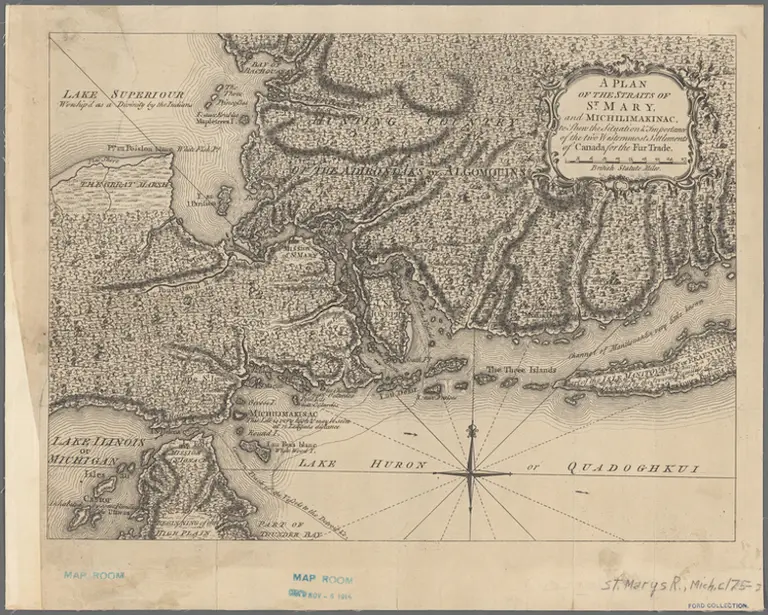

The history of Central Park’s Hooverville, the Great Depression shanty town

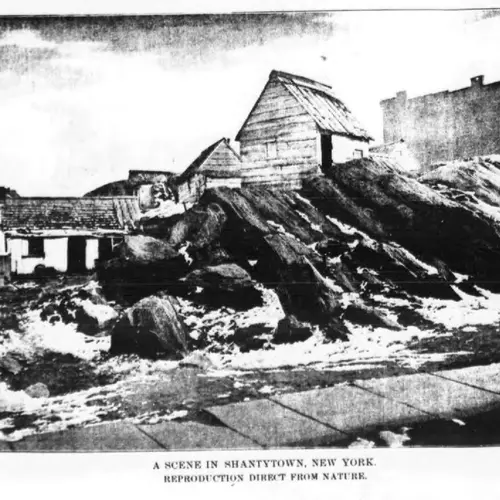

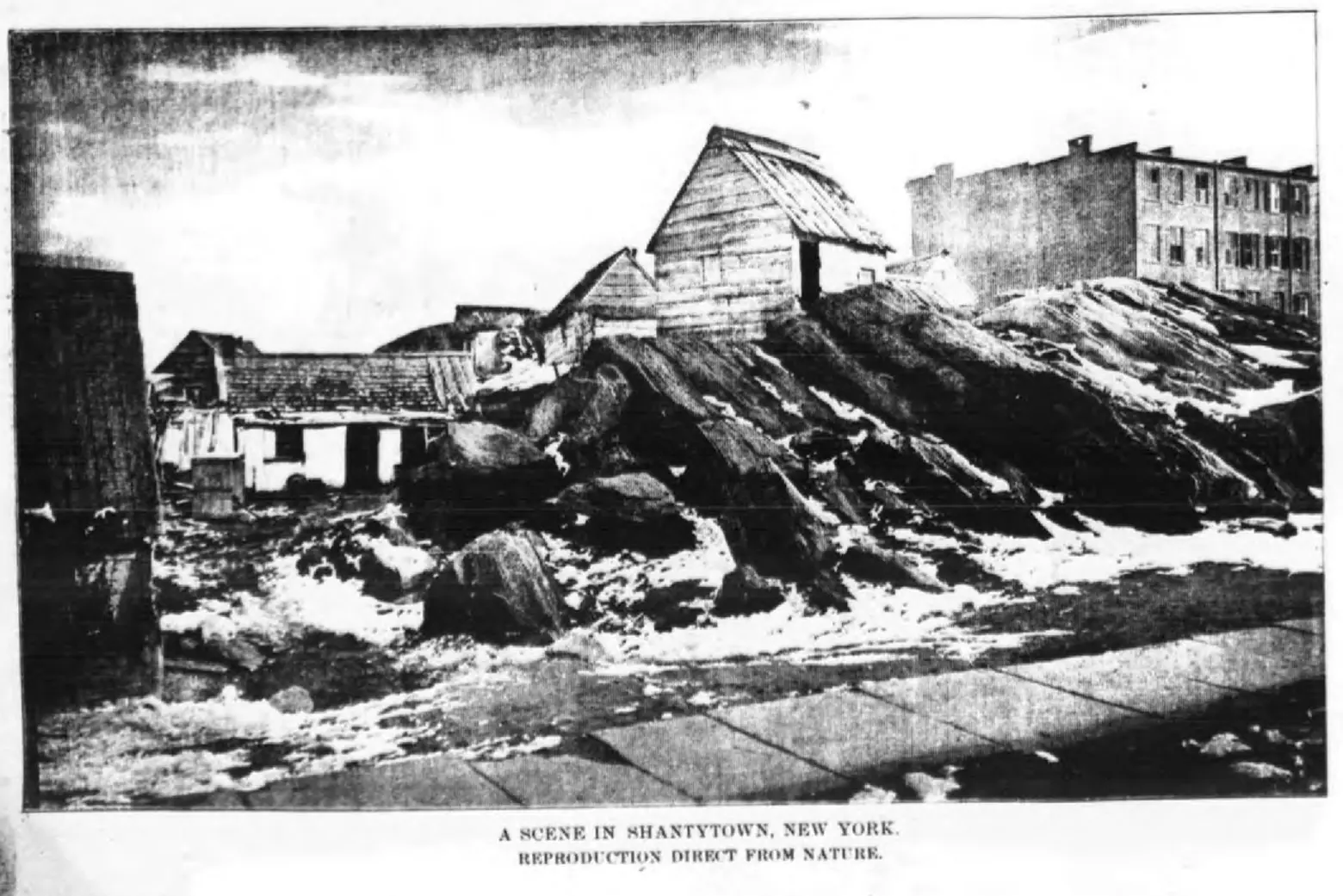

“A Scene in Shantytown, New York” appearing in the March 4, 1880 edition of the New York Daily Graphic, via Wikimedia Commons

Following the October stock market crash of 1929, there was an unprecedented number of people in the U.S. without homes or jobs. And as the Great Depression set in, demand grew and the overflow became far too overwhelming and unmanageable for government resources to manage. Homeless people in large cities began to build their own houses out of found materials, and some even built more permanent structures from brick. Small shanty towns—later named Hoovervilles after President Hoover—began to spring up in vacant lots, public land and empty alleys. Three of these pop-up villages were located in New York City, the largest of which was on what is now Central Park’s Great Lawn.

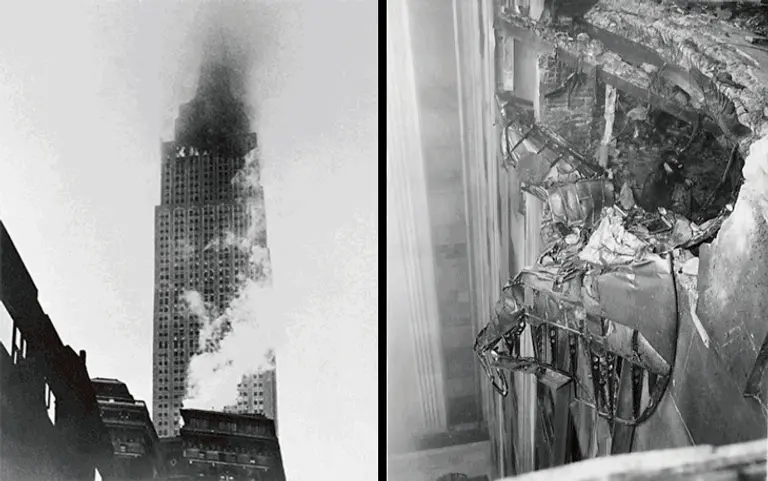

At the same time as the stock market crash, the reservoir in Central Park, north of Belvedere Castle, was drained and taken out of service, leaving a large expanse of open land for what would become the Great Lawn. The construction planned for the area had been delayed due to the economic crisis.

Late in 1930, a number of people had already begun to set up camp in this area but were quickly evicted by the police. However, as the Depression progressed and conditions worsened, attitudes changed and public sentiment became more sympathetic. In July of 1931, 22 unemployed men sleeping in the park were arrested, but upon sentencing, the charges were dropped and the ruling judge gave each of the men two dollars from his own pocket. It was also assumed that the tenants of the new Fifth Avenue and Central Park West apartments did not consider these men to be welcomed guests, but even they did not protest their presence.

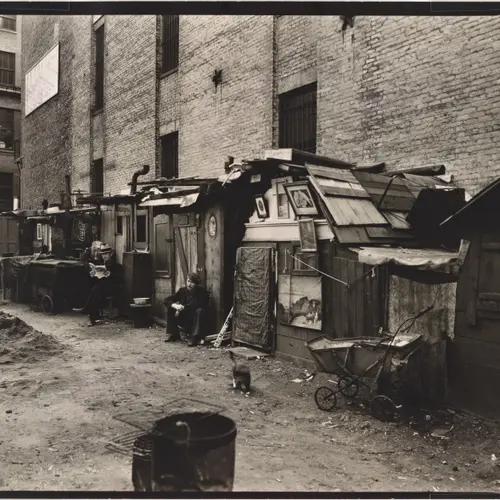

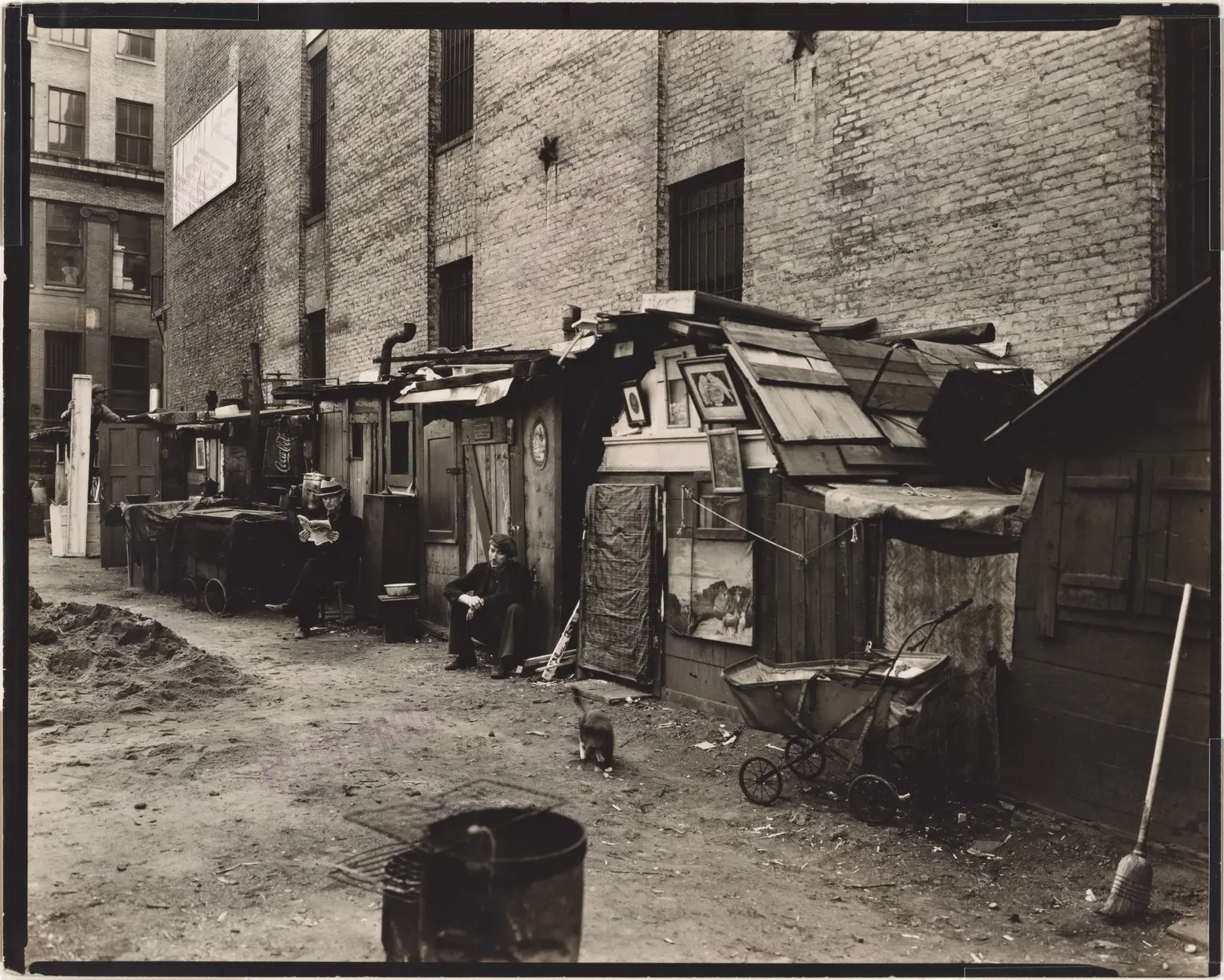

In December of that year, the New York Times reported living quarters for nine men including six shacks, one with a stove. One of the men was quoted, “We work hard to keep it clean, because that is important,” pointing to the care and consideration Hooverville residents gave their unconventional homes. Shortly after, seven of the men were arrested as vagrants, but the charges were dismissed. The article also reported on the daily routine of the men consisting of morning repairs to their comfort stations where they would shave and make themselves presentable.

Additional arrests continued, but in many of these cases, the charges were dropped. For example, in September of 1932, a total of 29 men were taken into custody, but the Parks Department was later quoted saying, “with apologies and good feelings on both sides,” when speaking about what they referred to as “Hoover Valley.”

By that time, Hoover Valley had expanded to 17 shacks running along “Depression Street,” each containing chairs and beds. Unemployed bricklayers built what was called the “Rockside Inn,” a brick building with a roof made from inlaid tile.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Huts and unemployed, West Houston and Mercer St., Manhattan.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1935.

According to “The Park and the People: A History of Central Park,” by Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, there were 1.2 million Americans homeless in the winter of 1932-1933, and 2,000 of them were New Yorkers. Similar settlements appeared in other neighborhoods of the city—one called “Hardlucksville” included 80 shacks between 9th and 10th Streets on the East River. Another called “Camp Thomas Paine” was located along the Hudson in Riverside Park. The Central Park encampment was the most famous and disappeared sometime before April 1933, when work on the reservoir landfill resumed and the economy was in recovery.

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on November 17, 2015.