The history of Weeksville: When Crown Heights had the second-largest free black community in the U.S.

Historic Hunterfly Road Houses via the Brooklyn Historical Society

It’s a mighty sounding moniker, but the name “King’s County” also speaks to Brooklyn’s less-than-democratic origins. At the turn of the 19th century, the city of Brooklyn was known as the “slaveholding capital” of New York State and was home to the highest concentration of enslaved people north of the Mason-Dixon Line. But, after New York State abolished slavery in 1827, free black professionals bought land in what is now Crown Heights and founded Weeksville, a self-supporting community of African American Freedman, which grew to become the second-largest free black community in Antebellum America. By 1855, over 520 free African Americans lived in Weeksville, including some of the leading activists in the Abolitionist and Equal Suffrage movements.

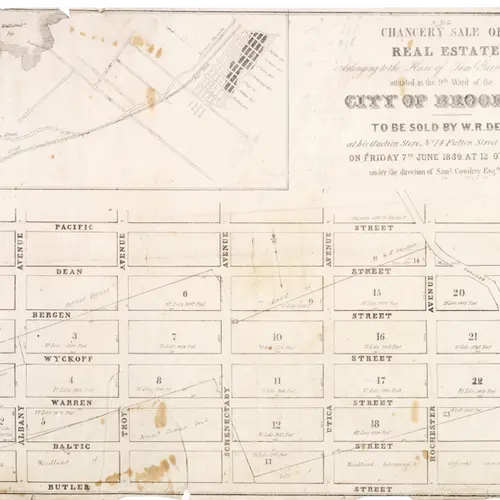

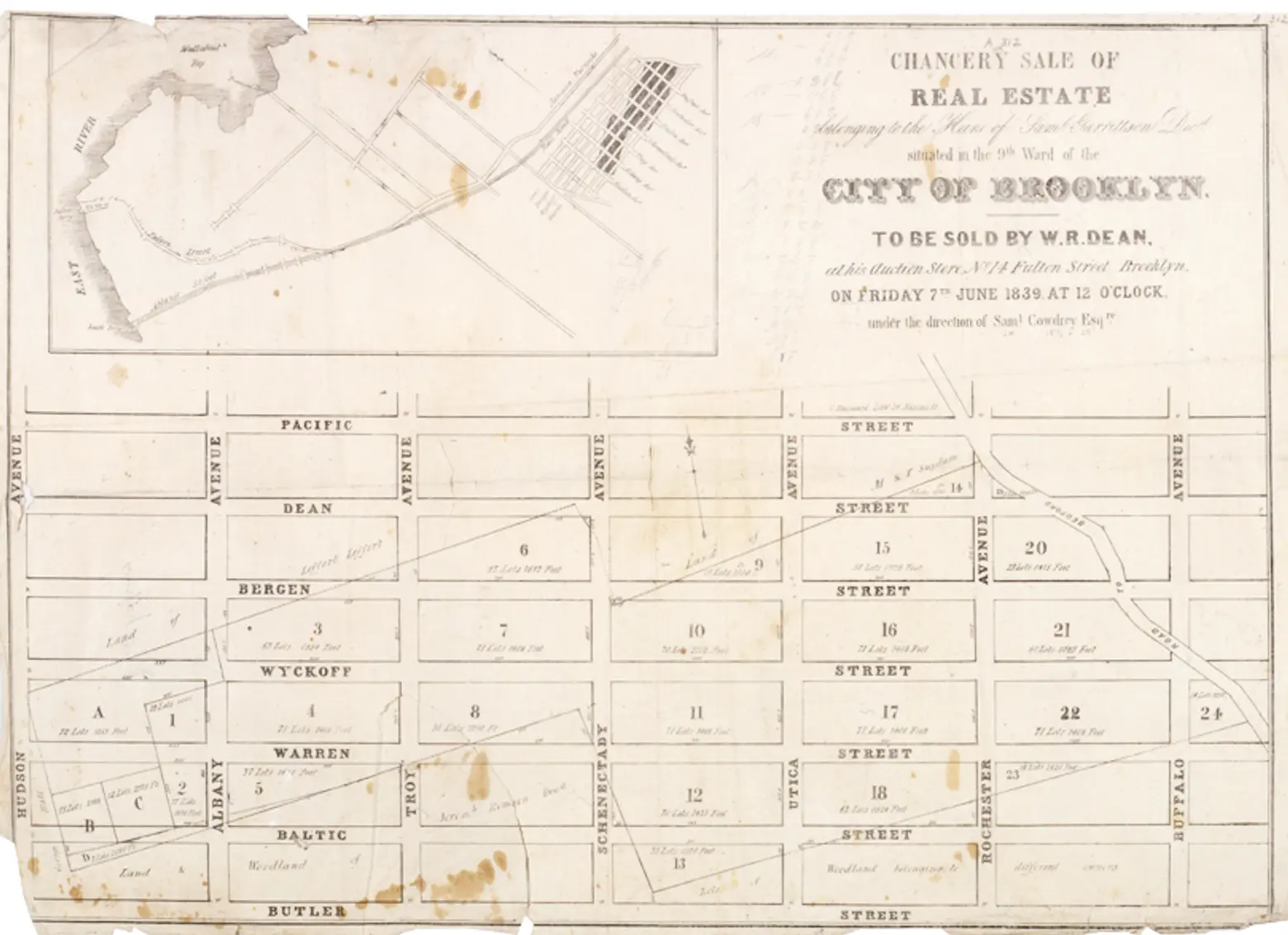

1839 deed of Sale for land in Brooklyn’s 9th Ward, which became Weeksville via the Brooklyn Historical Society

1839 deed of Sale for land in Brooklyn’s 9th Ward, which became Weeksville via the Brooklyn Historical Society

Weeksville was carved out of central Brooklyn when the Panic of 1837 moved wealthy landowners in the area to start liquidating their holdings. The Abolitionist and black community leader Henry C. Thompson purchased 32 lots from John Lefferts, whose family estate comprised most of what is now Bedford Stuyvesant and Crown Heights.

Map showing the historic borders of Weeksville, via Wiki Commons

Map showing the historic borders of Weeksville, via Wiki Commons

Thompson began selling those plots to other free black Brooklynites, including James Weeks, who purchased two plots in 1838, built a home near what is now Schenctady Avenue and Dean Street, and lived in the community that bears his name. Weeksville grew until its borders ran approximately to what are now East New York, Ralph, Troy, and Atlantic Avenues.

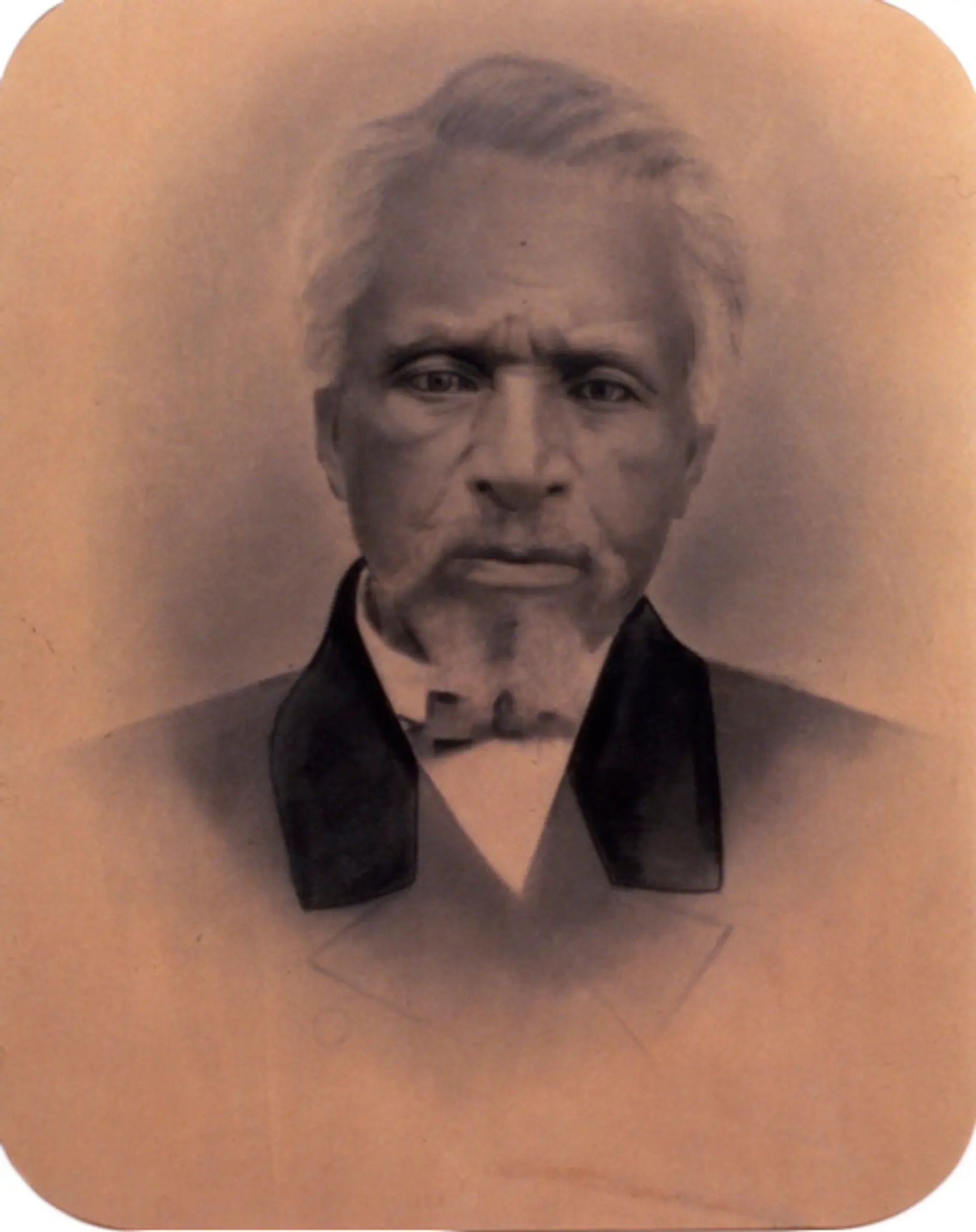

Sylvanus Smith, one of Weeksville’s original founders circa 1870 via the Brooklyn Historical Society

Sylvanus Smith, one of Weeksville’s original founders circa 1870 via the Brooklyn Historical Society

James Weeks, Sylvanus Smith, and the other original founders of Weeksville intentionally created a community, nestled among the slopes and valleys of Bedford Hills, that was geographically separate from the rest of Brooklyn. The seclusion helped ensure that community members would be safe and that Weeksville residents would have access to education, economic self-sufficiency, and political self-determination.

For free blacks in early 19th century New York, political self-determination and voting rights were directly tied to land ownership. In 1821, the New York State Constitution widened the franchise to include all white men regardless of whether they owned property but established a $250 property requirement for black men. Weeksville was the answer: a community of free black landowners.

Colored School No. 2 (PS 68) via the Brooklyn Historical Society

Colored School No. 2 (PS 68) via the Brooklyn Historical Society

Weeksville not only boasted the highest rate of property and business ownership in any African American urban community at the time, but also the community supported the nation’s first African American newspaper, the Freedman’s Torchlight, and built Colored School No. 2, which, after the Civil War, became PS 68, the first integrated school in the country.

Other cultural organizations included Zion Home for the Aged; Howard Colored Orphan Asylum; Berean Baptist Church; Bethel A.M.E. Church; Citizens Union Cemetery and, the African Civilization Society, an organization that worked to establish a colony of free blacks in Liberia.

Residents were moved by the idea of a free black colony in Liberia because Weeksville was founded during the Back to Africa Movement, which has been called the “golden age” of Black Nationalism. While some Weeksville residents, including the clergymen Henry Highland Garnet and T. McCants Stewart, did emigrate to Liberia, most of the community’s efforts regarding freedom, emancipation, education, and self-determination played out closer to home.

For example, according to a notice in its first issue, published by the African Civilization Society on Dean Street in 1866, The Freedman’s Torchlight was “devoted to the temporal and spiritual interests of the Freedman, and adapted to their present need of instruction in regard to simple truths and principles relating to their life, liberty and pursuit of happiness.” The paper contained reading lessons that were used to teach literacy to members of the community who had been denied that training under slavery.

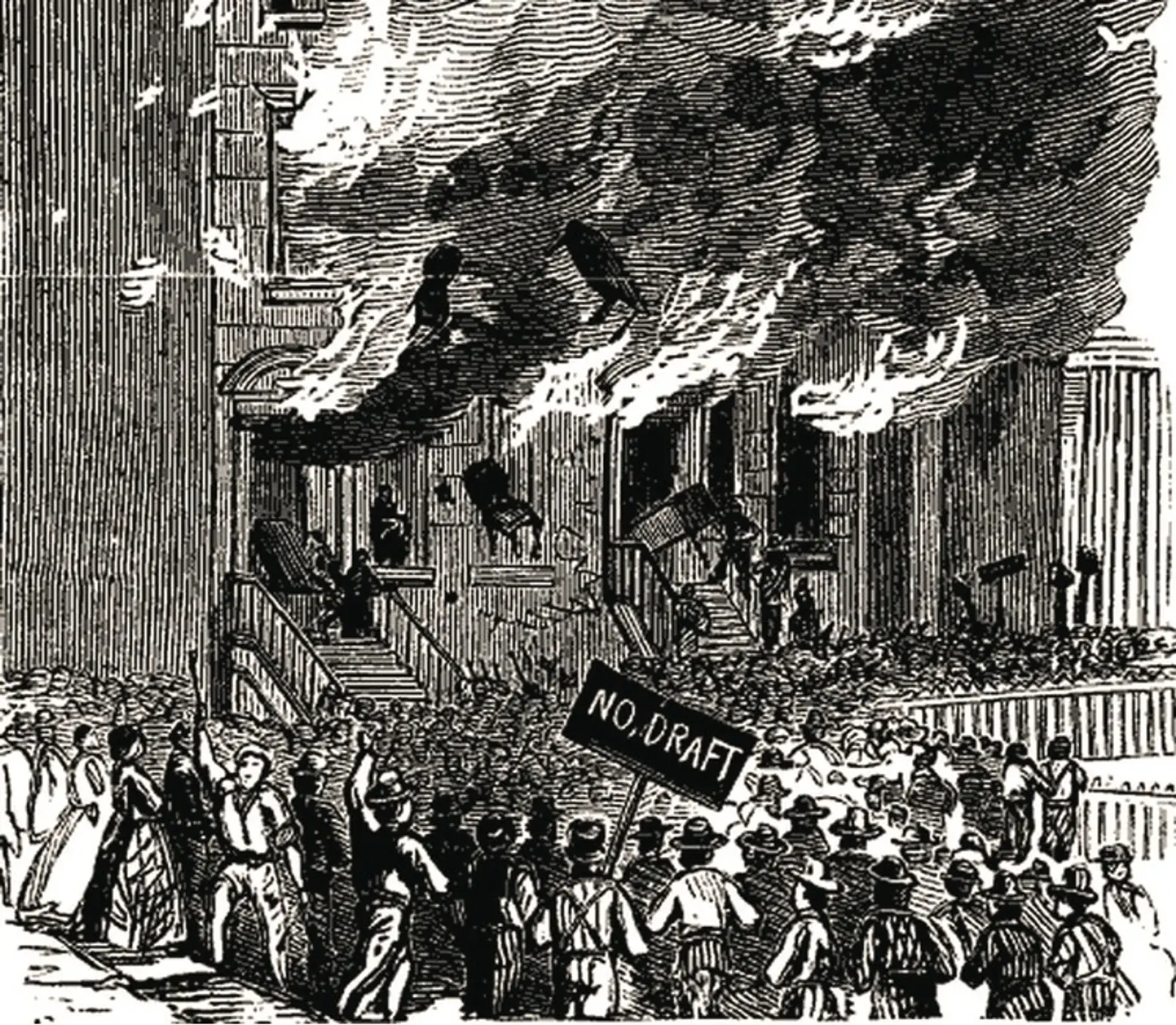

New York’s black community was targeted during the city’s 1863 draft riots via the Tenement Museum

New York’s black community was targeted during the city’s 1863 draft riots via the Tenement Museum

Weeksville not only offered more opportunities for education, employment and political enfranchisement for African Americans than anywhere else in Brooklyn, but also the community functioned as one of the principal safe havens for black New Yorkers threatened by the 1863 draft riots.

When opposition to the Civil War prompted Irish New Yorkers to target African Americans during bloody violence that bested the city’s police forces, and could only be broken by the arrival of Union Soldiers, Weeksville residents helped keep other New Yorkers safe.

The community’s focus on both self-determination and social justice for other African Americans made Weeksville home to extraordinary pioneers and community leaders. For example, Junius C. Morel was principal of Colored School No. 2, and also a nationally recognized journalist, who wrote for the Colored American, North Star, Frederick Douglass’ Paper, and Christian Recorder. In his writing, he advocated for both African American independence and racial and gender integration in public schools.

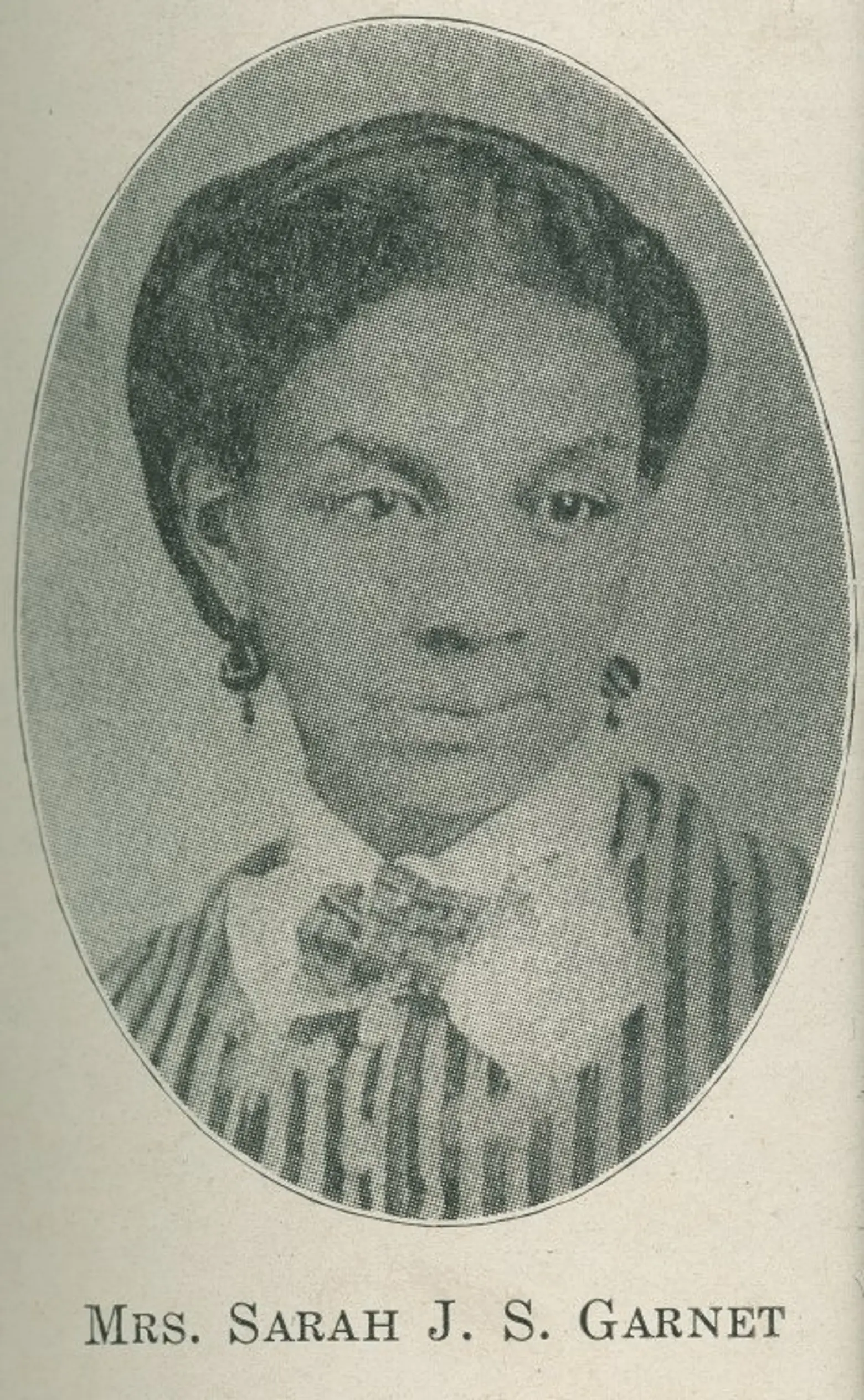

Sarah Smith Garnet was one of Sylvanus Smith’s daughters. She grew up in Weeksville and became one of the nation’s foremost educators and activists via the Brooklyn Historical Society

Sarah Smith Garnet was one of Sylvanus Smith’s daughters. She grew up in Weeksville and became one of the nation’s foremost educators and activists via the Brooklyn Historical Society

The women of Weeksville were also some of the most accomplished women in the country. For example, Susan Smith McKinney Steward became the first African American female doctor in New York State, and her sister, Sarah Smith Tompkins Garnet, became Brooklyn’s first female school principal and was the founder of the Equal Suffrage League of Brooklyn, the first suffrage organization founded by and for black women. Together, both sisters founded the Women’s Loyal Union of New York and Brooklyn, another black women’s suffrage organization.

The community thrived and grew throughout the 19th century, but, by the 1880s, Brooklyn had grown up around Weeksville, and it ceased to be secluded. Instead, Eastern Parkway came roaring through town, and residents began to disperse. By the early 20th century, Weeksville was all but subsumed into Brooklyn and largely forgotten.

1970s era community preservation project via the Weeksville Heritage Center

1970s era community preservation project via the Weeksville Heritage Center

Then came an airplane. In 1968, Pratt researchers James Hurley and Joseph Hays found references to Weeksville in 19th century histories of Brooklyn. Hurley was a historian, and Hays was a pilot. The two took to the air looking for remnants of Weeksville. They found four homes on Hunterfly Road, which are the oldest standing structures in Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights, and are the only homes left that were part of Weeksville.

Hurley and Hays began a campaign against time to save the homes, for the area had been targeted for a host of urban renewal projects. In 1969, Bed-Stuy resident Joan Maynard created the Society for the Preservation of Weeksville and Bedford Stuyvesant History in order to discover and preserve Weeksville’s past and to restore the Hunterfly Road Houses.

Hunterfly Road Houses today, via Wiki Commons

Hunterfly Road Houses today, via Wiki Commons

Thanks to her tireless advocacy, and the ardent support of the local community, the Hunterfly Road Houses were designated New York City Landmarks in 1970, and all four were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

The Weeksville Heritage Center’s modern new digs. Photos by Nic Lehoux for Caples Jefferson Architects.

The Weeksville Heritage Center’s modern new digs. Photos by Nic Lehoux for Caples Jefferson Architects.

The Society purchased the houses in 1973 and opened the Weeksville Heritage Center in 2005. In 2014, the Center expanded, adding a new, modern building. Today, the Weeksville Heritage Center offers tours, public programs, and research facilities to “document, preserve and interpret the history of free African American communities in Weeksville, Brooklyn and beyond.”

Through 2018, The Weeksville Heritage Center is partnering with the Brooklyn Historical Society and Irondale Theater to create In Pursuit of Freedom, exhibits, and programs designed to “celebrate & commemorate the rich Abolitionist and radical history of Brooklyn, from downtown (Dumbo, Brooklyn Heights, and Williamsburg) to historic Weeksville.” The exhibitions are now on view at both the Weeksville Heritage Center and The Brooklyn Historical Society.

+++

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

RELATED: