The New York bagel: The ‘hole’ story from history and chemistry to where you’ll find the good ones

Image via Wikimedia Commons

A few international symbols of New York City–like the tough cabbie, the expensive apartment and the pizza-snatching rat–need no explanation and are too scary to think about except when absolutely necessary. Others, like the humble-yet-iconic bagel, possess New York City cred, but when asked, most people can’t quite come up with a reason. Bagels weren’t invented in New York, but the party line is that if they’re made here, they’re better than anywhere. Some say it’s the water; others chalk it up to the recipe, the method, ethnic preference or all of the above. What’s the story behind the New York bagel? Who are the true bagel heroes? What makes a great bagel great? And those frozen bagels? Blame Connecticut.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

In an interview with the New York Times, Maria Balinska, author of “The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread,” said, “A New York bagel has a shiny crust with a little bit of hardness to it and a nice glaze. The inside is very chewy, but not overly doughy. It’s got a slight tang to the taste, and it’s not too big. But some people might disagree.”

Traditional bagels are made from wheat flour, salt, water, and yeast leavening. High gluten flours are preferred, as they yield the firm, dense bagel shape and chewy texture. Most bagel recipes call for the addition of a sweetener to the dough. Leavening can be accomplished using a sourdough technique (as with #1 rival, the Montreal bagel) or commercially produced yeast.

The magic happens by:

- mixing and kneading the ingredients to form the dough

- shaping the dough into the traditional bagel shape, round with a hole in the middle, from a long thin piece of dough

- proofing the bagels for at least 12 hours at low temperature (40–50 °F = 4.5–10 °C)

- boiling each bagel in water that may contain additives such as lye, baking soda, barley malt syrup, or honey

- baking at between 175 °C and 315 °C (about 350–600 °F)

The result: bagel taste, chewy texture, and shiny outer skin.

In recent years a variation known as the steam bagel has added to the mix in which the boiling is skipped and the bagels are baked in a steam-injection oven instead. The result is fluffier, softer and less chewy–sacrilege to bagel purists who believe that eating a bagel should be a bit of a struggle–kind of like living in New York.

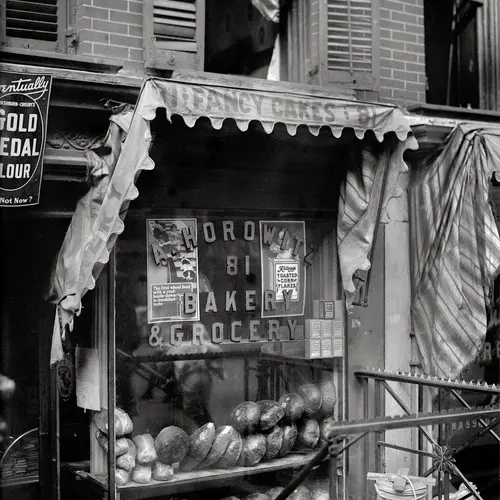

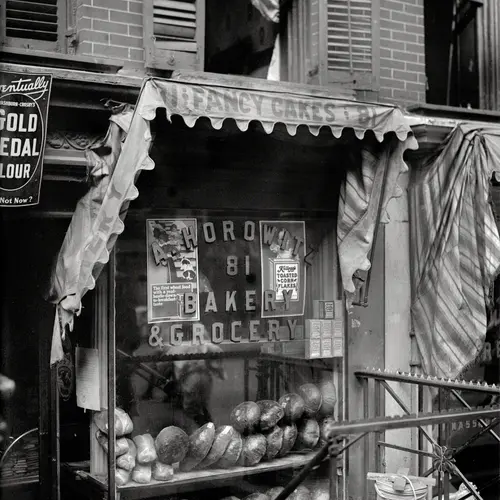

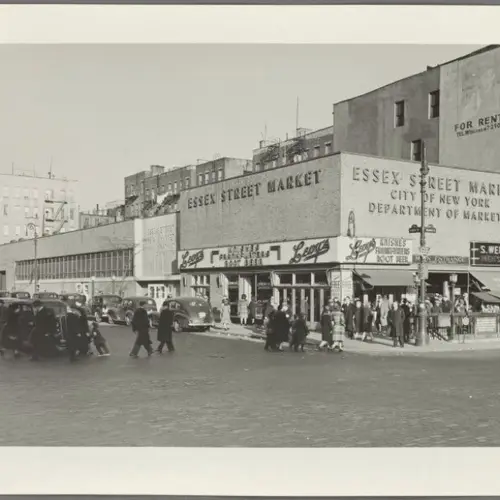

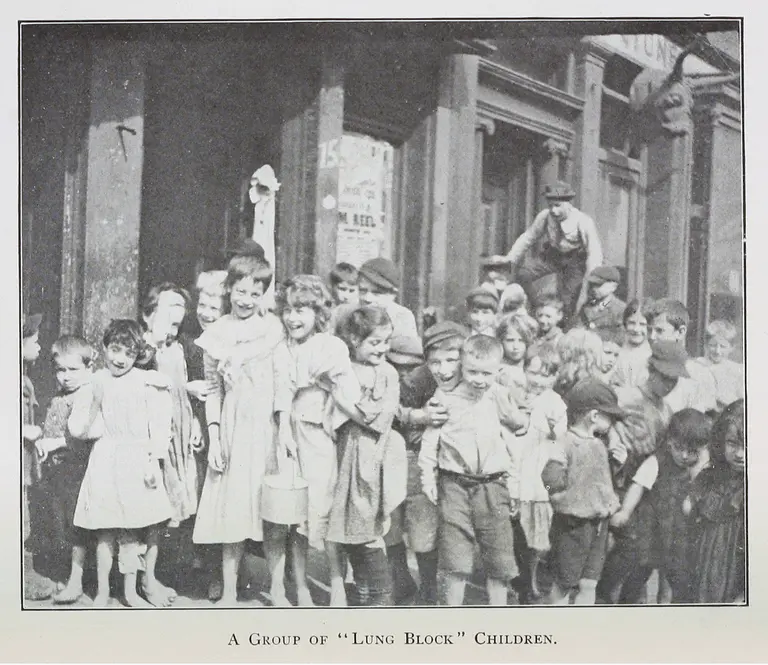

Where were the poppy-or-sesame seeds of this special recipe first sprinkled? Bagels were widely consumed in Ashkenazi Jewish communities in the 17th century. The first known mention was in 1610 in the Jewish community ordinances in Kraków, Poland. The boiled-and-baked bagel as we know it was brought to America by Polish Jews who immigrated here, which led to a thriving business in New York City that was controlled for decades by Bagel Bakers Local 338. The union had contracts with nearly all bagel bakeries in and around the city for its workers, who prepared bagels by hand.

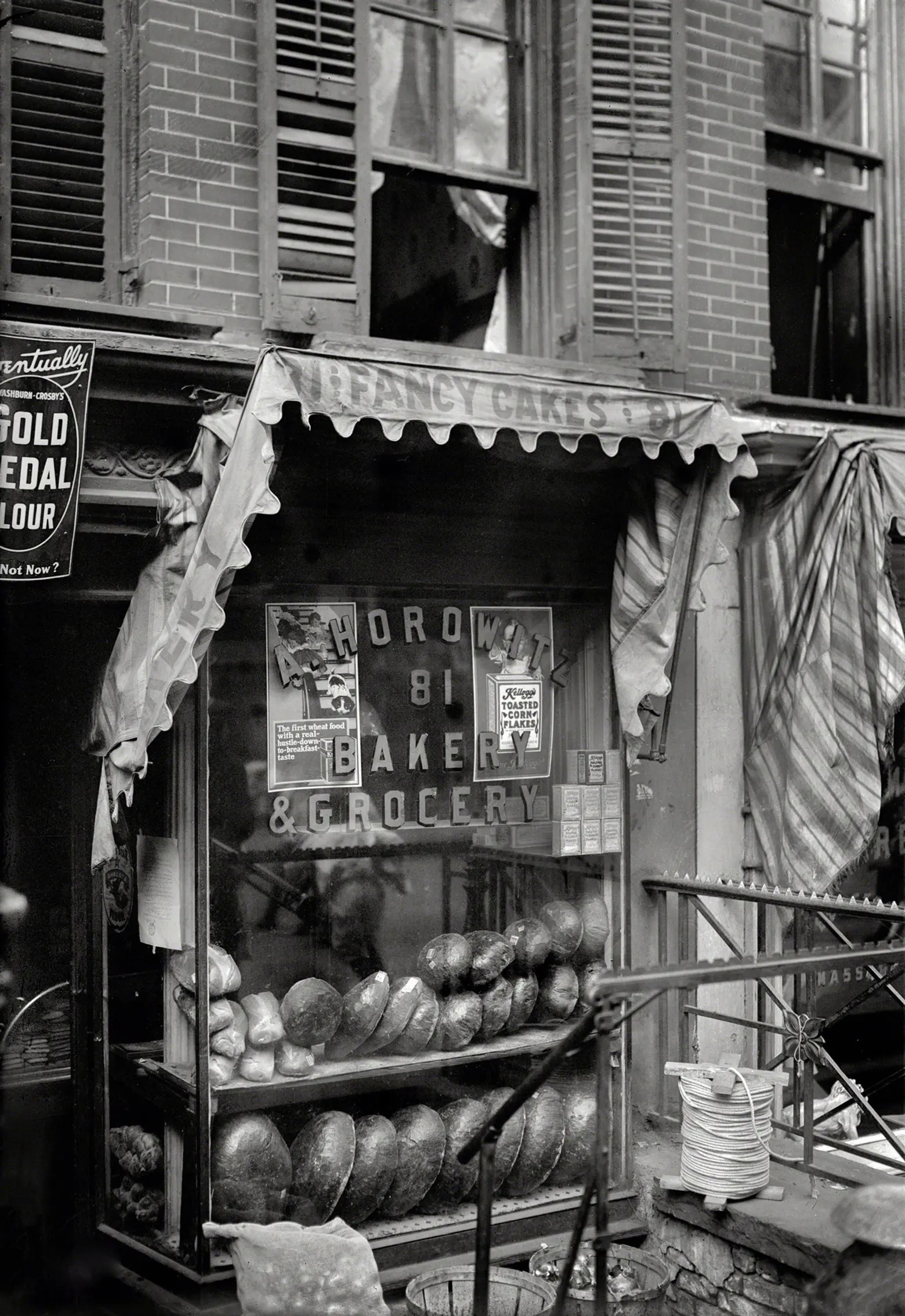

Image courtesy of George Grantham Bain Collection via Flickr.

Untapped Cities tells us that by 1900, 70 bakeries existed on the Lower East Side; in 1907, the International Beigel Bakers’ Union had monopolized bagel production in the city. If their demands weren’t met, the bakers went on strike, causing what the Times called “bagel famine.” In December of 1951, 32 out of 34 bagel bakeries closed, leaving shelves bare and sending lox sales swimming upstream. The strike was eventually resolved by the State Board of Mediation’s Murray Nathan, who had reportedly worked similar magic for the lox strike of 1947. With the dawn of the 1960s, the bagel’s popularity had spread to the far corners the nation (h/t atlas obscura). The New York Times dubbed New York City “the bagel center of the free world.

Then technology disrupted everything. New tech allowed for the simultaneous preparation of 200 to 600 bagels at a time. Daniel Thompson started work on the first commercially viable bagel machine in 1958. Bagel baker Harry Lender, his son, Murray Lender and Florence Sender leased this technology and pioneered automated production and distribution of frozen bagels in the 1960s. Murray also invented pre-slicing the bagel.

Murray Lender may be the nemesis of bagel purists, but he was a hero to NYC diaspora in bagel deserts like the Midwest, where a frozen bagel was definitely better than no bagel at all. For the first time, bagels were being sold right to customers. Lender’s bakery in New Haven, Connecticut started mass-producing bagels, and selling them bagged and frozen to supermarkets. By 1980, bagels were fully integrated into the daily lives of New Yorkers–and beyond.

Image: BarbaraLN via Flickr

Image: BarbaraLN via Flickr

Culture Trip reports that in the early 1950s, Family Circle magazine offered readers a recipe for bageles (their spelling): “Stumped for the Hors d’oeuvres Ideas? Here’s a grand one from Fannie Engle. ‘Split these tender little triumphs in halves and then quarters. Spread with sweet butter and place a small slice of smoked salmon on each. For variations, spread with cream cheese, anchovies or red caviar. (They’re also delicious served as breakfast rolls.)’ “

One writer opines in Slate that while bagels are ethnic in origin, they don’t declare their ethnicity with loud flavors, spices or appearances, which makes it not unusual that some of today’s most beloved New York bagel bakeries are not necessarily under Jewish ownership: A Puerto Rican family owns H&H Bagels, where a Cincinnatian of German ancestry bakes Cincinnati Red, tropical fruit and taco bagels; Absolute Bagels is owned by a Thai couple on the Upper West Side.

Euro cup pride bagels. Image via Wikimedia Commons

And New Yorkers, of course, can’t even agree on what makes a bagel sublime. The Times gets some input:

• It “should be crunchy on the outside and chewy on the inside,” according to Melanie Frost, CEO of Ess-a-Bagel, in Midtown East. “And they should be hand-rolled.”

• “They should always be boiled, never steamed,” said Bagel Hole of Park Slope’s Philip Romanzi.

• Niki Russ Federman, o-owner of Russ & Daughters on the Lower East Side, tells us what a New York bagel is not. “It should not be sweet and you should never find blueberries, jalapeños, or rainbow colors in your bagel.”

• According to Adam Pomerantz, owner of Murray’s Bagels in Greenwich Village, New York bagels have a hole and lots of of seeds on both sides and should also be slightly well-done. “A bagel should be a bit of struggle to bite into. That’s what a true New York bagel is all about.”

Are New York bagels better? One theory–which may have some truth to it–attributes their taste to New York’s water. New York’s water possesses a perfect ratio of calcium to magnesium, making it especially “soft.” This soft water bonds well with the gluten in the dough making for a perfectly chewy bagel.

Most New York bagel shops also do the two key things said to create the perfect bagel: They allow the dough to sit in a refrigerator to assist in the fermentation process before rolling it, which creates a richer flavor. They then boil the dough in a mixture of water and baking soda, which results in the bagel’s shiny outer layer and chewy inner layer.

Bagel squirrel. Image: Jesse Millan via Flickr.

When the flour settles, the bagel symbolizes a nourishing tasty snack that–like pizza, with a similar rep–can be piled high with favorite ingredients and taken to go. What’s more, bagels provide an opportunity to voice one’s passionate opinion about where to find the best one. And what do New Yorkers love more than that?

The contenders

Whenever talk turns to bagels, a few familiar names rise to the surface: H & H Bagels, Ess-a-bagel, David’s bagels, Kossar’s Bialys on the Lower East Side and Murray’s bagels of Greenwich Village. But to a bagel connoisseur, the landscape is far more geographically diverse.

According to Grub Street, Utopia bagels in Whitestone Queens holds the number one spot, followed by Absolute Bagels and Bo’s Bagels of–gasp–Harlem. Also on the list are relative newcomer Tompkins Square bagels, Sadelle’s and Terrace Bagels of Windsor Terrace among others. The Bagel Hole of Park Slope is also a list regular. Eater puts their picks for top bagel stops on a map.

Facts and figures

In the era of gluten-free and low-carb, one wonders if the doughy delight is destined to become ancient history–but the numbers suggest otherwise. According to the American Institute of Baking (AIB), 2008 supermarket sales (52-week period ending January 27, 2009) of the top eight leading commercial fresh (not frozen) bagel brands in the United States totaled to US $430,185,378 based on 142,669,901 package unit sales.

A typical bagel has 260–350 calories, 1.0–4.5 grams of fat, 330–660 milligrams of sodium, and 2–5 grams of fiber. Gluten-free bagels have much more fat, often 9 grams, because of the presence in the dough of ingredients that supplant wheat flour in the original.

Around 1900, the “bagel brunch” became popular in New York City. The bagel brunch consisted of a bagel topped with lox, cream cheese, capers, tomato, and red onion.

In Japan, the first kosher bagels were brought by BagelK from New York in 1989. BagelK created green tea, chocolate, maple-nut, and banana-nut flavors for the market in Japan. There are three million bagels exported from the U.S. annually. Some Japanese bagels, such as those sold by BAGEL & BAGEL, are soft and sweet; others, such as Einstein Bro. bagels sold by Costco in Japan, are the same as in the U.S.

RELATED: