The story behind Harlem’s trailblazing Harriet Tubman sculpture

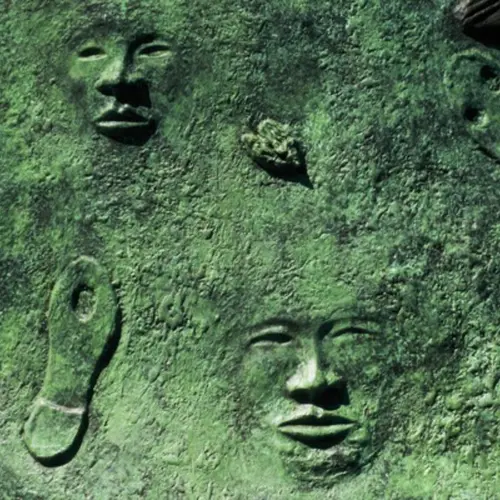

Photo of Harriet Tubman Memorial, “Swing Low,” in Harlem via denisbin on Flickr

Harriet Tubman, the fearless abolitionist and conductor of the Underground Railroad who led scores of slaves to freedom in some 13 expeditions, fought for the Union Army during the Civil War, and dedicated herself to Women’s Suffrage later in life, was known as “Moses” in her own time, and is revered in our time as an extraordinary trailblazer. Her status as a groundbreaking African American woman also extends to the now-contentious realm of public statuary and historical commemoration, since Tubman was the first African American woman to be depicted in public sculpture in New York City.

Tubman’s statue, also known as “Swing Low,” was commissioned by the Department of Cultural Affairs’ Percent for Art program, and designed by the African-American artist Alison Saar. It was dedicated in 2008 at Harlem’s Harriet Tubman Triangle on 122nd Street. In her memorial sculpture, Saar chose to depict Tubman “not so much as a conductor of the Underground Railroad, but as a train itself, an unstoppable locomotive that worked towards improving the lives of slaves for most of her long life.” She told the Parks Department, “I wanted not merely to speak of her courage or illustrate her commitment, but to honor her compassion.”

The sculpture, realized in bronze and Chinese granite, depicts Tubman striding forward, pulling up “the roots of slavery” in her wake. Stylized portraits decorate Tubman’s skirt. The portraits, many of which were inspired by West African “passport masks,” honor the Underground Railroad passengers Tubman helped lead to freedom. Bronze tiles around the statue’s granite base depict events in Tubman’s life, as well as traditional quilting patterns. Linking the statue to its environment, Harriet Tubman Triangle is landscaped with plants native to both New York and Tubman’s home state of Maryland.

Since its 2008 dedication, this statue too has generated controversy: Tubman is facing south, instead of North, toward freedom. A petition that garnered over 1,000 signatures from members of the Harlem community in 2008 sought to have the statue reoriented so that Tubman would be striding north, but Saar explained that it was her artistic vision to depict Tubman making the trip south to help free slaves still in bondage.

Saar told Percent for Art, “The community largely saw it as the figure not facing the direction of the Underground Railroad, which was northbound. But for Harriet Tubman it was a two-way street, going back and forth, and that’s how I wanted to remember her. People kept demanding that she be turned around. What was nice about all of that was that it really opened up a dialogue with the surrounding community.”

As the dialogue around public statuary and historical commemoration continues to evolve, it has come to light that just 5 of New York City’s nearly 150 historical statues honor women. (In addition to Tubman the women so honored are Joan of Arc, Eleanor Roosevelt, Golda Meir and Gertrude Stein).

To address that imbalance, NYC First Lady Chirlane McCray has established the She Built NYC campaign to honor female leaders in public sculpture around NYC. Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman to serve in the House of Representatives and to run for President, will be the first person memorialized as part of the She Built NYC Program. Chisholm’s statue will be dedicated near Prospect Park in 2020.

That year will also see the first statue of historical women dedicated in Central Park, as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton take their place on the Park’s Mall. As more women are honored through public art, Tubman’s statue takes on added significance as a symbol leading the city toward a broader, more inclusive, historical narrative.

RELATED: