This 1970s East Village Windmill Was Decades Ahead of Its Time

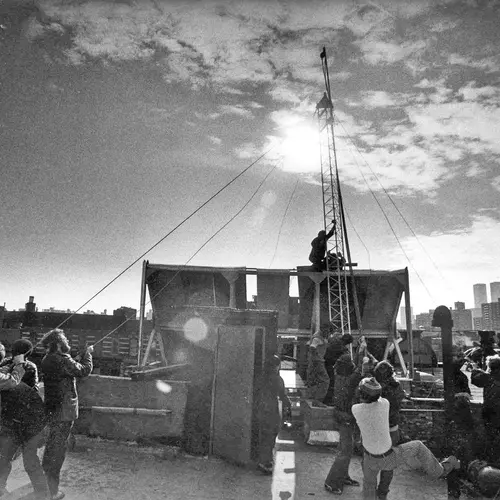

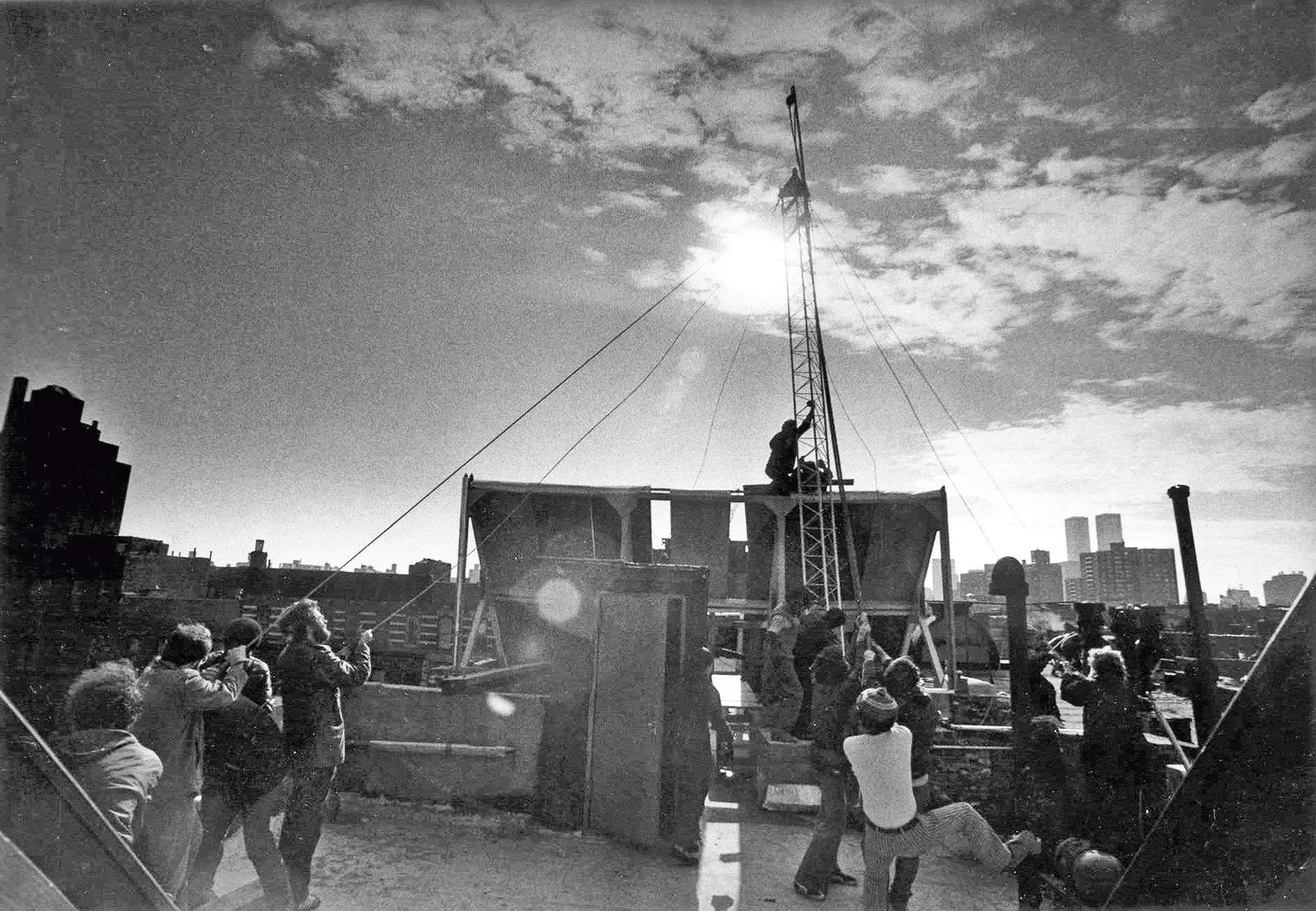

Raising the windmill on the roof of 519. Photo credit: Travis Price via Gothamist

If you want to build a windmill today, you can thank a handful of dedicated tenants in a building at 519 East 11th Street in the East Village of the 1970s.

The story of the Alphabet City windmill is one of many stories, recounted in Gothamist, from the bad old days of Loisaida–as the East Village‘s far eastern avenues, also known as Alphabet City, were once called–the kind the neighborhood’s elder statesmen regale you with, knowing well that you know nothing firsthand of a neighborhood of burned-out buildings and squatters who bought their homes for a buck. But this particular story isn’t one of riots or drug deals on the sidewalk; it’s one of redemption, no matter how brief in the context of time.

The windmill was installed above an East Village building that was saved by the community, built and lifted to the roof by hand–or many hands. According to legend, the windmill kept the lights on during the chaos of the 1977 blackout.

“The windmill has given us a new sense of pride because it was the unemployed and unskilled people of the neighborhood that put this 37 foot tower into the air. The windmill itself has grown to be a symbol of self help.”

At the time, neighborhood buildings were being burned daily for insurance payments. Community and tenant groups formed to provide residents with basic tenants’ rights for anyone who dared reside there. Self-help housing programs like the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB) and Division of Alternative Management Program (DAMP) formed to turn abandoned buildings over to neighborhood residents to repair and eventually own–a radical proposition at the time.

In 1974 DAMP came to discover the building at 519 East 11th Street; it had been completely abandoned and torched; a stripped car blocked the front hallway. The group purchased 519 East 11th Street from the city for $100 a unit–$1,600 total. They were fortunate enough to also get a $177,000 housing loan to do a complete renovation–the last low-interest housing loan from the city before bankruptcy nixed the program. The group offered workers that put in the time in construction hours a chance to be part of the co-op that owned the building afterwards. An apartment would cost $500, or equivalent time in sweat equity.

In 1976, a young student named Travis Price arrived in New York City from New Mexico, where he had been working with a radical solar group who were building solar collectors and wind generators in the desert. Price had a contract to work on a government paper on energy conservation for the Nixon administration–a huge focus at the time of the 1973 oil embargo and increased fuel costs. Unlike many arrivals in the Big Apple, he began looking around to see where he could help, seeking “low-income housing projects, to see if I could help the least, last and lost with solar energy.”

Price happened across the tenants of building 519, hard at work. He saw what they did not: They’d need a lot more insulation or a better energy solution to achieve the independence that was their goal. At the time, the idea of solar energy was about as foreign to most people as something from a sci-fi movie, but thinking the project was perfect for a solar experiment, Price told the tenants he could use it to heat their hot water.

In his first of many well-timed publicity opportunities, Price wrote a grant proposal for insulation and solar collectors and submitted it to the head of the Community Services Administration, then in charge of federal funding for community development. He borrowed a solar collector from friends at Yale, set it up and and invited Congressman Richard Ottinger–and some news networks–for a photo-op. They got their funding to build solar collectors on the roof and insulate the building.

Construction progressed slowly; unskilled workers came and left. According to Norris, “The ones who stayed became this sort of forced collective and organized to do a lot of hard, physical labor to get the building done. So it was an interesting group of people…”

Inexperience was the theme then; at one point the co-op of 12 people held a strike against itself for higher wages. 519 became “a sort of a ‘sagrada familia’—the sacred family of the neighborhood.” The idea began to catch on and more buildings nearby got involved in homesteading, and community gardens sprouted nearby. 519 East 11th Street started to look like home. People stayed in their apartments. They received 30 Sunworks solar collectors, and painted each panel a different bright color. According to reports, solar heating kicked in on March 16, 1976. After a year, the heating fuel bill was $48 a year, per room, per year (compared to $110 for conventional heating).

When Ted Finch joined the 519 collective, he brought with him an interest in wind power. Finch had found an old, non-working wind machine “somewhere in the Midwest,” and fixed it up to put on top of the building. In a strictly no-permits situation, it took the entire crew, plus extra helpers–paid in cases of beer–to haul the 12-foot-wide wind machine to the roof and install it atop a 45-foot steel base, where it would be able to generate two kilowatts of electricity–enough to power the solar collectors and light all of the common space in the building’s hallways and its neighboring gardens.

Norris recounts, “Once it was up there, you had four ropes that were trying to keep the top in one place and a bunch of guys down at the bottom lifting it up, hoping that it didn’t topple over.” There was no precedent for a wind machine of that kind in 20th century New York. On the windmill’s feather tail they had put the logo, “El Movimiento de la Calle Once:” The 11th Street movement. According to Price, “Everybody was proud of it. It was kind of a symbol of something extraordinary, as small as it was. In a neighborhood where all hope is gone, everything is burnt out, suddenly someone is rebuilding.”

The 519 windmill and solar panels; photo: Shawn G. Chittle

The wind machine worked by the propeller turning a turbine behind the nose. Whatever small amount of excess energy there was, was stored on ConEd’s grid. All of this happened in the very shadow of the the ConEd factory, which loomed above Avenue C just two blocks away. The experiment was a success, but a week later the group was being sued by Con Ed.

Fortunately Ramsey Clark, former Attorney General for the United States, believed the case was “the biggest thing since the civil rights movement” and immediately volunteered to defend them. ConEd’s lawsuit eventually became about the issue of co-generation–whether an independent building could generate its own electricity and force ConEd to purchase it when it fed it back through the meter. In one of the first deregulating acts against the monopolized energy companies, the Public Service Commissioner ruled in favor of building 519, and the nationwide Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) was passed, which would allow non-utility generators to exist.

A certain amount of fame ensued, as did visits from the mayor, Robert Redford and the MacNeil/Lehrer news hour program. “When Ted Kennedy flew into New York during the 1977 blackouts and looked down over lower Manhattan it was all dark, except for one twinkling light: 519 East 11th Street.”

Price, Tabor, Norris and the original crews have long since relocated. The building changed hands in 1980, and the neighborhood changed, and changed again. The original homesteaders inspired community gardens and sparked more residents to organize tenants and rehab buildings, which went a long way toward changing the neighborhood from a combat zone to a desirable place to live. This may have worked against the neighborhood eventually; but for a time, there was nowhere else that could sustain the kind of dedication and curiosity that put a windmill on the roof of 519.

[via Gothamist]

RELATED: