University in Exile: How refugees at the New School helped win WWII and transform American scholarship

L’Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes at the New School in 1942, via France-Amerique

In 1937, the great German writer Thomas Mann suggested “To the Living Spirit” as a motto for the New School’s University in Exile. Since the Nazis had removed the same motto from the great lecture hall at the University of Heidelberg, the phrase would “indicate that the living spirit, driven from Germany, has found a home in this country,” and that home was on West 12th Street.

Between 1933 and 1945, The New School’s University in Exile offered asylum to more than 180 refugee scholars from fascist Europe. The exiled academics became the Graduate Faculty of The New School for Social Research and represented the largest contingent of refugee intellectuals in the United States. In the classroom, they made pioneering advances in the social sciences; in the war room, they advised the Roosevelt Administration on economic policy, war information, and espionage. Educating future Nobel Prize winners as well as future Oscar winners, they influenced American scholastic and cultural life to such a degree that even Marlon Brando remembered his émigré professors at the New School, “enriching the city’s intellectual life with an intensity that has probably never been equaled anywhere during a comparable period of time.”

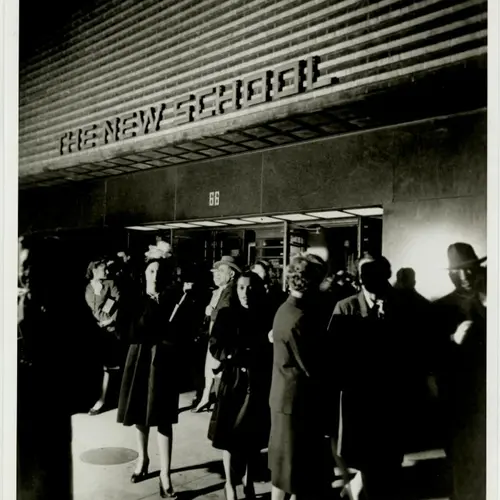

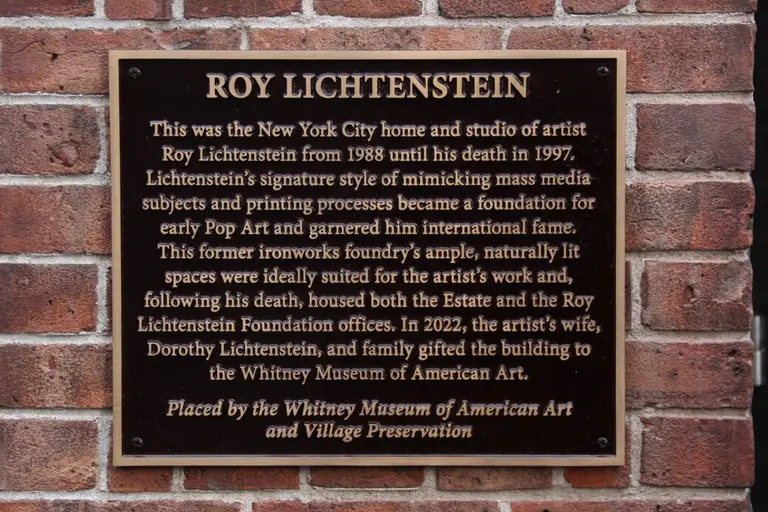

The New School, 66 West 12th St. via The Rumpus

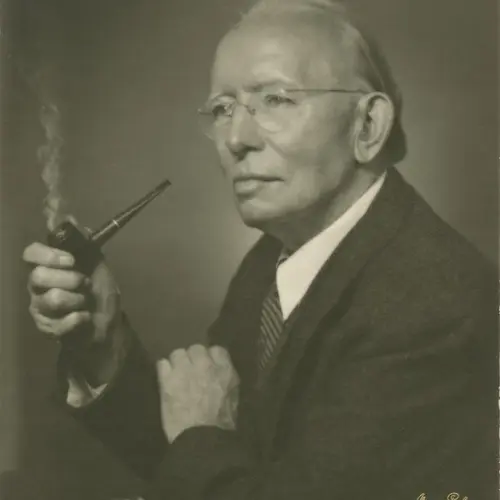

The refugee scholars found such a vigorous home at The New School because the entire institution had been structured, in part, on the German adult school model. Since German scholarship in the social sciences lead the field in the 1920s, The New School maintained close ties to German intellectuals. In 1927, when New School director Alvin Johnson became co-editor of The Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, he solicited work from scholars in Germany, who made him aware of the increasingly dire political situation in Europe. In April 1933, when 16 percent of all German university faculty were immediately dismissed from their posts, Johnson leaped into action before most Americans grasped the gravity of the situation.

He observed, “the world is quick to forgive invasions of academic liberty by a forceful government. It long ago forgave Mussolini. It will never forgive Hitler as long as we have a working University in Exile.”

With that conviction in mind, he made a “protest in deeds” on behalf of academic freedom. With an advisory board including former Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, he began a furious fundraising campaign to provide salaried positions at The University in Exile for Germany’s most lauded economists and social scientists.

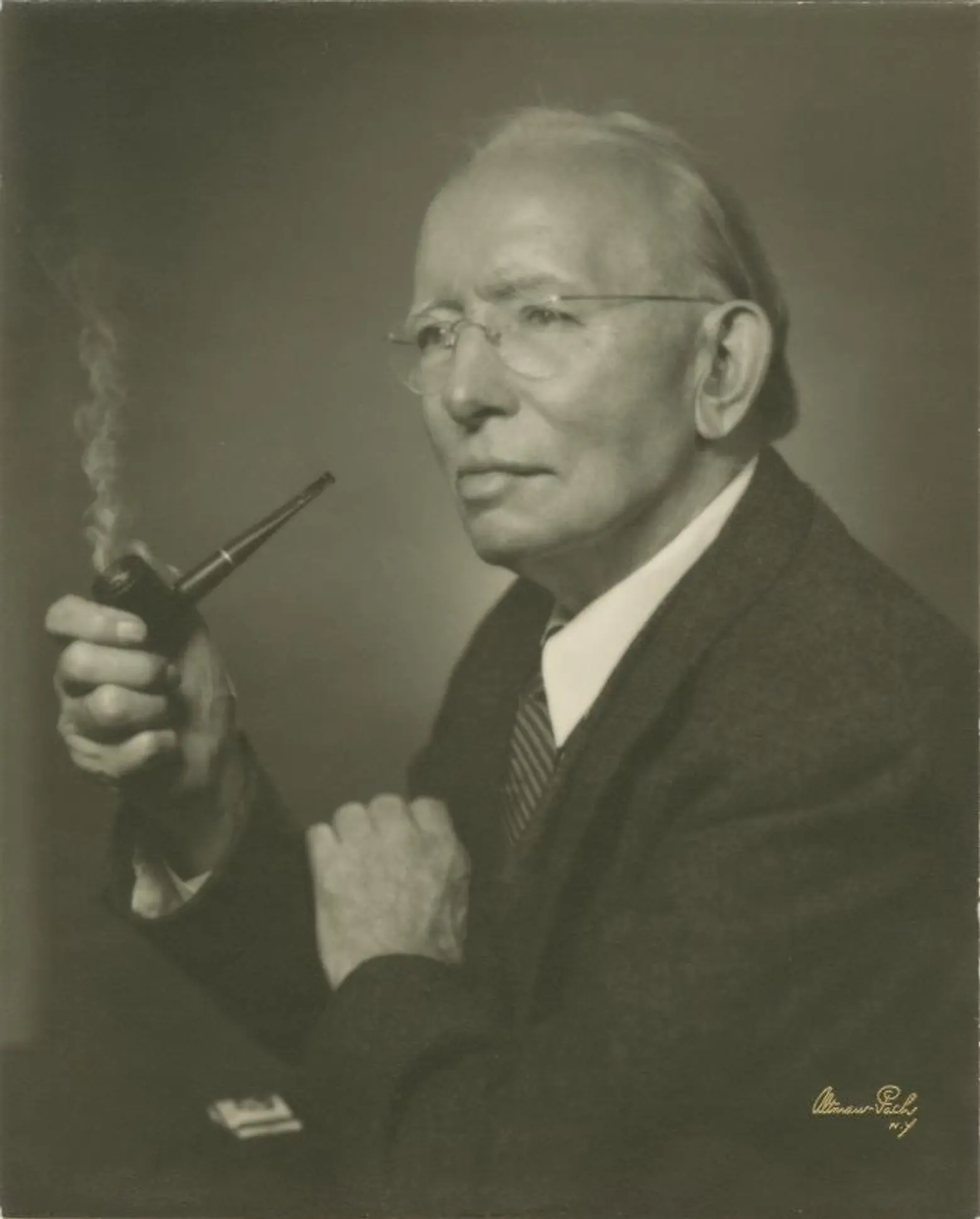

Alvin Johnson, 1938 via The New School

Appealing to the “international solidarity of scholarship” and “for the sake of American science and the national interest which it serves,” he was able to secure an initial donation from the philanthropist Hiram Halle, and a sustaining donation from the Rockefeller Foundation. Johnson’s work on behalf of the refugee scholars was so passionate, and so immediate, that the first group of intellectuals, ousted in April 1933, began teaching at the New School on October 2nd of that year.

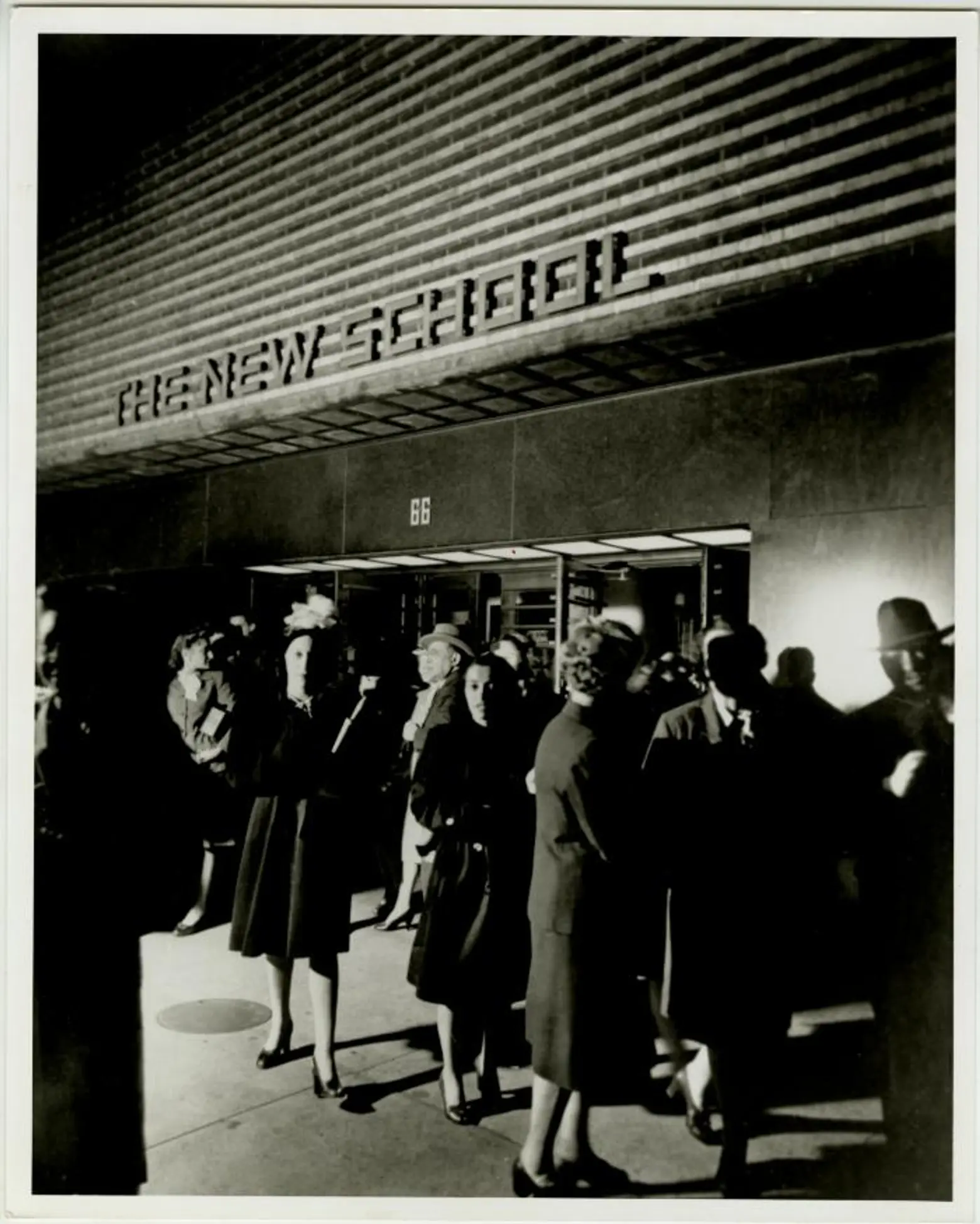

The exiled faculty at the beginning of their first semester, October 4, 1933 via The New School

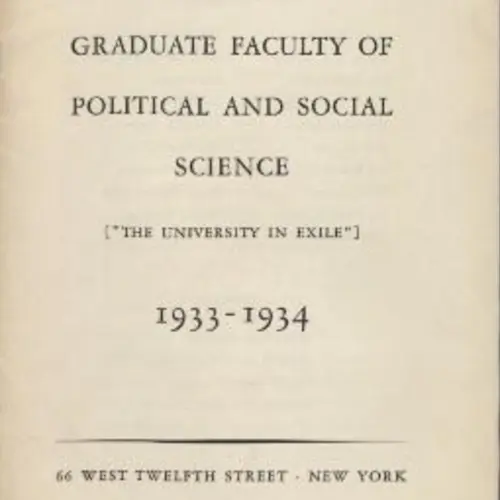

That fall, ten refugee scholars came to the New School as the founding members of the University in Exile. Max Wertheimer brought his pioneering Gestalt Theory of psychology; sociologist Freida Wunderlich lectured on social politics; Erich von Hornbostel taught comparative musicology; Herman Kantorowicz extolled the sources and science of law; economists Eduard Heiman, Karl Brandt, Gerhard Colm, Arthur Fieler, Hans Speier and Emil Lederer offered courses on the history of economic thought, the relationship between private and public finance, international economic relations, social stratification, and the theory of economic dynamics. They even offered a course on the question that bewitches American students to this day: “Has Capitalism Failed?”

University in Exile faculty, via The New School

University in Exile faculty, via The New School

The refugee faculty made the New School the most important center for social science in the country, but that illustrious distinction didn’t win the hearts of the American public – or even the American intellectual community. Then as now, public prejudice and paranoia curbed efforts to find positions for exiles in the United States.

In addition to traditional anti-Semitism, the refugees faced an isolationist public who imagined that the immigrant scholars were a “5th column of socialist agitators.” Accordingly, many American universities deliberately sabotaged efforts to place exiled intellectuals within their ranks. Harvard, for example, did not accept any refugee faculty, and Isaiah Bowman, president of Johns Hopkins, declared that The New School was “the only place the ‘refugee problem’ could be solved to everyone’s satisfaction.”

As it grew, the University in Exile offered asylum to approximately a quarter of the refugee scholars in the United States. But, with the nation in the throes of the Depression, which put nearly 10 percent of American university faculty out of work, the public still asked a question which echoes down the years: are they taking our jobs?

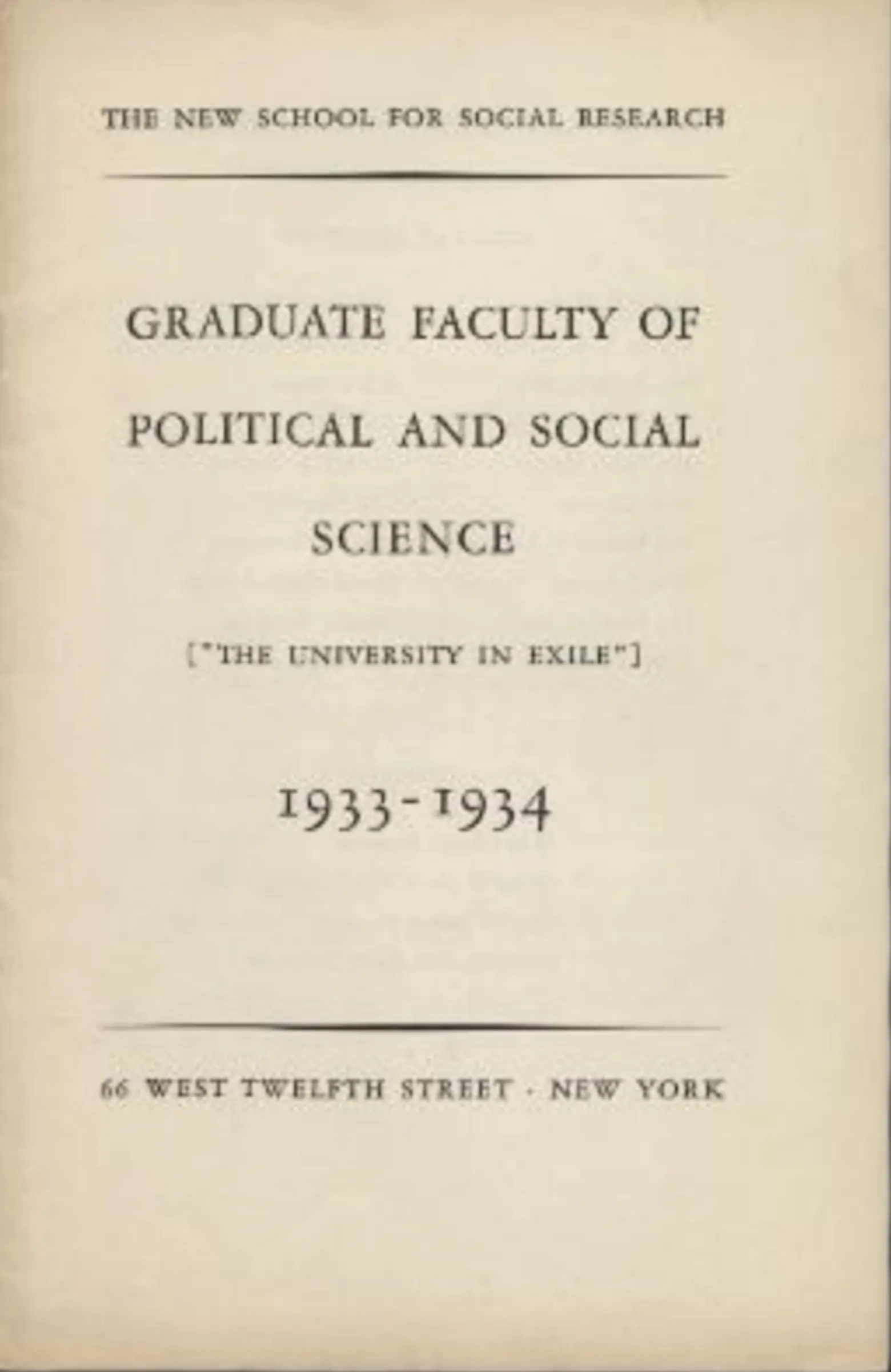

University in Exile’s first course catalogue, via The New School

University in Exile’s first course catalogue, via The New School

The firm answer: No. In April 1937, Professor John Brown Mason, of Colorado Women’s College, wrote of the 18 émigré professors then at the New School, “these faculty members are not occupying positions which our unemployed professors could fill, for American and German scholarship in these fields have long been recognized as complementary to each other rather than duplicating.” The difference, he continued, was that “usually, the Germans stress more historical and philosophical aspects of those subjects,” and “German social scientists in general, possess more practical experience than their American colleagues, gathered in the political life and governmental service of their country… as administrators or as expert advisors.”

Indeed, the exiles were the United States’ largest staff of experts on international affairs. For example, Arnold Brecht, the political scientist, had held posts in the ministries of Interior and Finance during the Weimar Republic, and served as the Prussian representative in the Reichsrat; Hans Simons, the son of the former acting president of Germany, had also served in the Ministry of the Interior, and been at the Conference of Versailles (where the infamous treaty was negotiated).

Given these bona fides, the émigré faculty became consultants to the US government, and several professors even held positions in Washington: The sociologist Hans Spier served in the Office of War Information, and in the State Department’s Occupied Areas division, as a propaganda specialist; Brecht was a supervisor in the Army’s German area training program; Simons was a department head in the US post-war military government in Germany.

Back home, as the US struggled against the Depression, the refugee intellectuals proved a great asset. The New Deal was showing that economic policy could help democratize society, and the refugee economists embraced Roosevelt’s program. Gerhard Colm even served as a financial expert in the Bureau of the Budget, and his work there culminated in the Full Employment Act of 1946.

The first issue of the Graduate Faculty’s quarterly, Social Research, via Social Research

The first issue of the Graduate Faculty’s quarterly, Social Research, via Social Research

The exiles not only helped implement the New Deal and win the war, but also they established the journal Social Research, which is published to this day, and originated the first research division at an American university staffed entirely by immigrants. In fact, their division is the basis of the New School’s current graduate program; it began offering degrees in 1935.

In solidarity with other scholars still in danger, the émigré faculty committed three percent of their salaries to make positions available for other academics. After the Anschluss, the faculty added several new members. Following the fall of France, the University in Exile joined the Rockefeller Foundation in a spectacular effort to make room at the New School for over 170 scholars from all over Europe.

By 1942, the University in Exile was a richly various, multinational body. Recognizing UiE’s large French scholarly community, including renowned thinkers like Claude Levi-Strauss, General de Gaulle’s Free French government put up $75,000 per year to establish the Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes, where courses were taught in French, as opposed to the ones offered in English by the German, Spanish and Italian faculty. The French scholars, The New York Times editorialized, “can keep the light burning here, and in God’s good time, re-illuminate the torches of humane learning in a liberated France.”

The University in Exile was at the vanguard of all things humane. Because it provided a place for the threatened scholarly traditions to flourish, and for threatened people to thrive, Justice Felix Frankfurter declared that UiE represented “the trusteeship of civilization.”

Fitting for such a humane crowd, many of the exiles, most of whom had already become American citizens, turned their sights toward “Peace Research,” helping the United States to define its place in the post-war world. Luckily, it was a place that included them.

+++

If you’d like to learn more about the New School and academic freedom in Greenwich Village, please join Lucie Levine on September 2nd for a tour with the Municipal Art Society, Back to School: Education and Radical Free Thought in Greenwich Village.

RELATED:

- How six Italian immigrants from the South Bronx carved some of the nation’s most iconic sculptures

- Reading between the lions: A history of the New York Public Library

- Going nuclear: The Manhattan Project in Manhattan

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Lucie Levine is the founder of Archive on Parade, a local tour and event company that aims to take New York’s fascinating history out of the archives and into the streets. She’s a Native New Yorker, and licensed New York City tour guide, with a passion for the city’s social, political and cultural history. She has collaborated with local partners including the New York Public Library, The 92nd Street Y, The Brooklyn Brainery, The Society for the Advancement of Social Studies and Nerd Nite to offer exciting tours, lectures and community events all over town. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.