Where I Work: Inside Stephen Powers’ colorful world of studio art and sign making in Boerum Hill

6sqft’s series “Where I Work” takes us into the studios, offices, and off-beat workspaces of New Yorkers across the city. In this installment, we’re touring artist Stephen Powers’ Boerum Hill studio and sign shop. Want to see your business featured here? Get in touch!

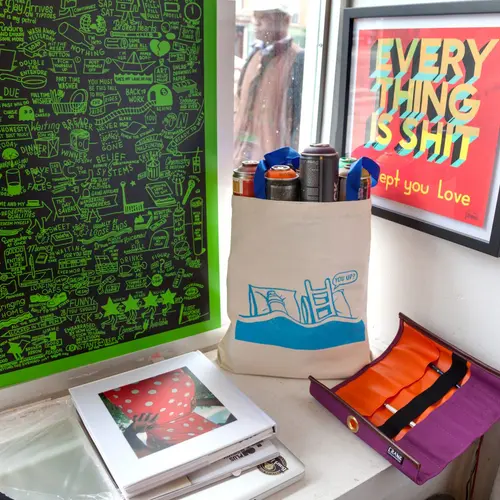

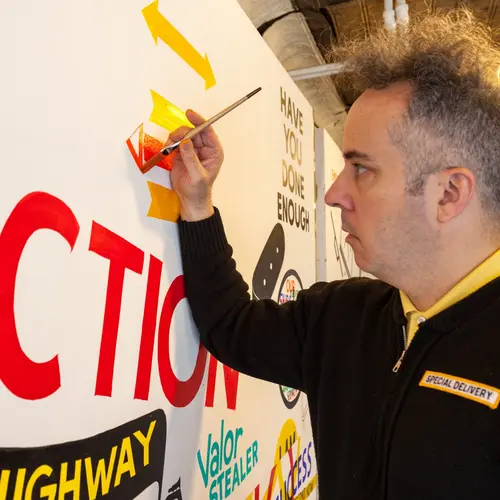

Walking along Fourth Avenue in Boerum Hill, the storefronts all look pretty similar–pizza shops, laundromats, cute cafes–until you come to the corner of Bergen Street and see the large, colorful collage of signs gracing the side of the little brick building. This is ESPO’s Art World, artist Stephen Powers’ sign shop. But as you can imagine, this space is much more than that. Powers, who painted graffiti under the name ESPO for much of the ’80s and ’90s in NYC and Philadelphia, also uses his shop as a retail store and informal gallery where passersby can walk in and peruse his graphic, pop-art-esque, text-heavy work. Stephen recently gave 6sqft a guided tour of his shop and chatted with us about his transition from graffiti to studio art, why he dislikes the term “street art,” his love for Brooklyn, and where he sees the art scene heading.

Stephen and his staff (and their two dogs!) welcome us in

Stephen and his staff (and their two dogs!) welcome us in

You’ve been in this studio/gallery space for five years. How and why did you transition from graffiti to studio art?

I painted graffiti from 1984 to 1999 and it was a pretty good time to transition, as I was 31 years old. It was high time for me to move on. I wanted to be an artist the whole time I was writing graffiti but I never thought of graffiti as an art form. I thought of it as graffiti. It was a self-advertisement. It was a way of knowing the city and architecture. It was the ways and means of promoting yourself in the city and it seemed to be a really effective, interesting sub-culture on its own. It didn’t seem to be art in any way. And I didn’t approach it any way that I would approach art.

An ESPO graffiti piece in the Bronx in the ’90s, taken for “Broken Windows: Graffiti NYC”

An ESPO graffiti piece in the Bronx in the ’90s, taken for “Broken Windows: Graffiti NYC”

I stopped writing graffiti at the same time I published a book on the subject, “The Art of Getting Over,” and I really wanted to be an artist. I had all these ideas I was thinking about. For me, graffiti was one word and art represented all the other words. So that was my transition out of it. I made what I thought was a really lateral move and kind of a weigh station between graffiti and art when I started sign painting.

How did you choose to learn sign painting?

There was some history that some [graffiti] artists had begun working with signage and sign painting. It seemed like a good midpoint for me between art and graffiti. I didn’t realize that it was going to open up all of these other avenues. For me, it started out being this really small alley of information and encapsulating ideas and then it opened up into this highway of thought, action, and possibility.

Tell us about your early success as a studio artist.

Within a year of deciding I was going to be an artist, my work was shown at the Venice Biennial [as an artist]. It was very interesting, weird, intimidating, and upsetting in some ways. I felt like I kind of got lucky. I was in the right place at the right time. I felt like I had gotten to the Super Bowl as a bench warmer or as a third-string quarterback. I didn’t get there on my own merits. I had all these ideas and was really just denigrating the work that I had done. I felt an intense need to start over, so I retreated.

I kept the sign paint and I kept the ideas but I thought I would start all over again and become a real sign painter. I wanted to paint signs in the same way as I had painted graffiti in the sense that I just really wanted to paint graffiti. When I painted graffiti, I wasn’t interested in making art or doing anything else with it. In order to become a sign painter, I needed a place where I could work where I wouldn’t necessarily be judged on the deficiencies I had as a sign painter. So I went to Coney Island and started painting signs.

Tell us more about the work you did in Coney Island.

During the time I painted signs in Coney Island, I learned about the materials and how much I was doing wrong. I started getting on the right path and also learned so much about Coney Island, which exists literally as a funhouse mirror of America in general. It really is like the id of the American landscape. All the worst ideas and all the best ideas manifest in Coney Island. It exists as a dream outside of normal life. And if you really want to understand New York, Coney Island is the best place to start. I thought I was going to work there for a summer but I ended up being there for five or six years doing all types of sign painting and morphing into doing art projects down there. I really transitioned from a sign painter into a full-fledged carny and then I felt like I was really ready to be an artist.

Do you also consider your work street art?

I am in my 19th year of being an artist and I’ve never heard the term street art that whole time. I don’t acknowledge it and I have nothing to do with it. For me, its not really street and it’s not really art and I don’t get it. And that’s fine. I think everyone has his or her own way. But my way is the way it’s always been. I look at the city as a place to play and to work and dream and to act. That’s why I am here every day.

How did you find this space in Brooklyn?

Before opening this studio I had a very large sign shop in Brooklyn, which was like a staging area where I could store my supplies and work out ideas. I brought in other people to help me and got used to having a space where people could come see me. When we got the opportunity to move to this smaller space, it became an interesting anecdote to the big-box galleries. At the same time, it’s a way to meet and interact with people and introducing them to my artwork and sell them my work. We even set up a print shop in the basement to screen print and make prints of the large pieces I’ve created.

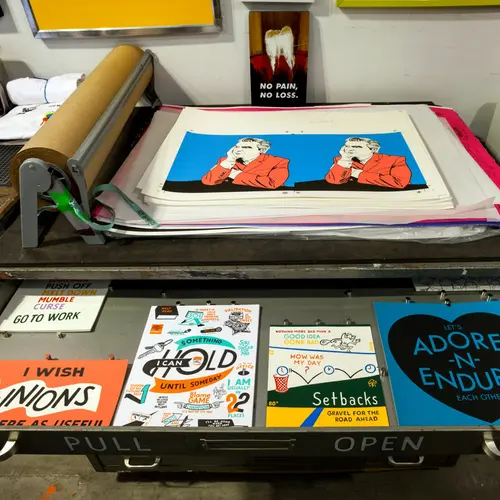

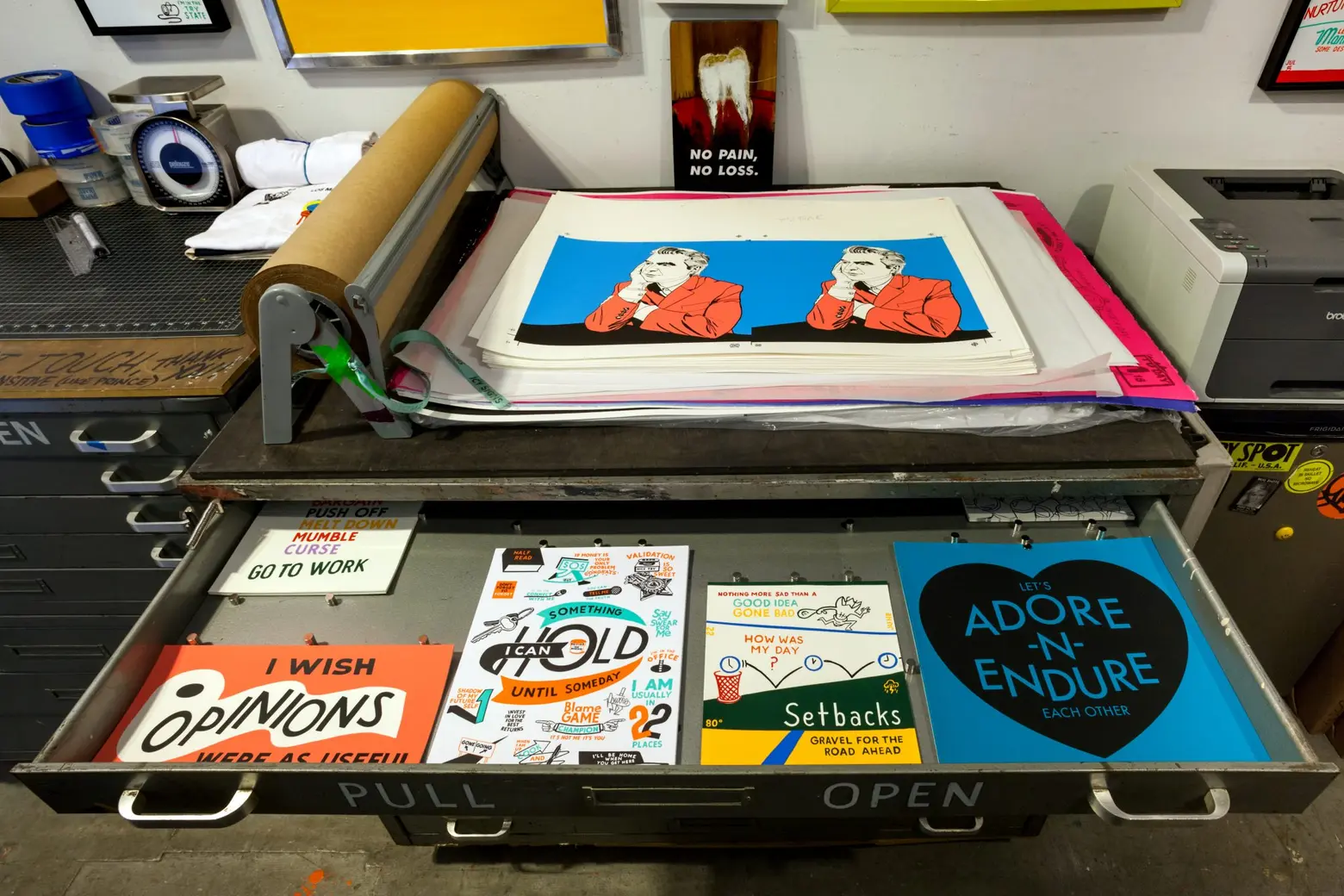

The basement screenprinting studio

The basement screenprinting studio

This space is perfect, but were you inclined to come to this neighborhood specifically?

This space was offered to us by a friend’s uncle who owned the building and was interested in having something art-related in here. It was formerly his studio and he was fending offers from pilates studios, which was actually the best worst offer he had. People wanted to rent the space and gentrify the corner and make it something it wasn’t. They wanted to extend Park Slope across the avenue into Boerum Hill and the landlord saw the upside and downside to that and didn’t want anything to do with it. So what we do here is provide an important function for him in occupying the space and keeping people from bothering him about renting the space. When we landed here I didn’t know anything about the block in particular. But it’s a really interesting block and we try to be a good neighbor and keep our sidewalks clean and even make signs for free for the activists down the block.

Do you get a lot of people popping in off the street?

We get a lot of people coming in looking to get keys made because there used to be a locksmith next door. One of these days we are going to get a key machine and really just do it for people. But I think just being here and being available is great. Anyone can just come in and charge their phone for free at our phone charging station.

Do you live in the neighborhood?

No, I live in Manhattan in the West Village. I am a reverse commuter.

Would you consider opening a studio in the West Village?

I would but it’s interesting in that the West Village is such a graveyard for ideas. You can’t open a space in the West Village now because the landlord will want $30,000 a month. Landlords, who own like 50 other properties and just want a tax write-off by keeping the commercial space empty, own most of the buildings. Mom-and-pop commerce in the West Village is in a death spiral. It’s insane to see but I think we will see the end of it in a few years. I hope that landlords will see the upside of having people rent their spaces at a fair market value.

How do you feel about the gallery scene in New York City overall?

The gallery scene in New York is really strange. There are a whole lot of new galleries on the Lower East Side that I see springing up. I don’t know if it’s a trend that is going to continue but for a few years now they have been reaching out and showing older artists that may have been under-represented on the scene for a few years and bringing them back out. It’s really great to see a lot of artists, my landlord for one, starting to show a lot more. It’s a nice combination of brand new galleries with good old New York talent filling the spaces. It’s great for artists like myself who are basically mid-career artists living in the lull of life. I feel like every artist has his or her time and artists have to work in the meantime. So this represents me figuring it out and finding my ways and means of making work and meeting people and not worrying about it too much.

Since social media has become so important in the last decade, has that changed how you approach things in your work?

Yes, it has become a time suck that I’m not really comfortable with. I am trying to navigate my way through it. It’s been amazing to expose my work and I think it’s being seen a lot more. I also think I get a lot of credit for things that normally in times past I would not. I think people are more accountable for what inspires them and they now credit their sources better than they used to. At the same time, everything is free now. What I mean is that as an artist, I can’t really cry about influencing people. I never could and I never really did. But now I think it’s more than ever. Artists have to understand that they are just vessels and temporary receptacles for whatever ideas pass through them. Nobody owns anything anymore. I think it’s great and it keeps me on my toes.

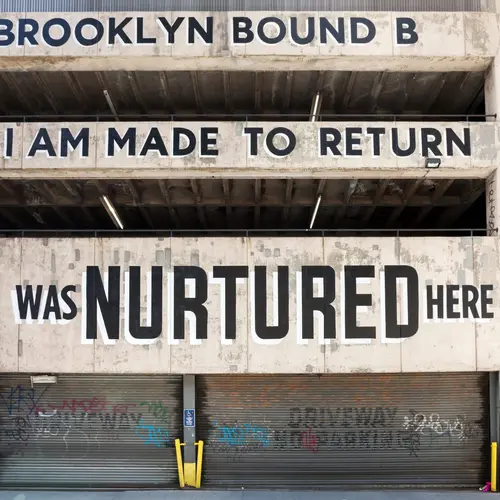

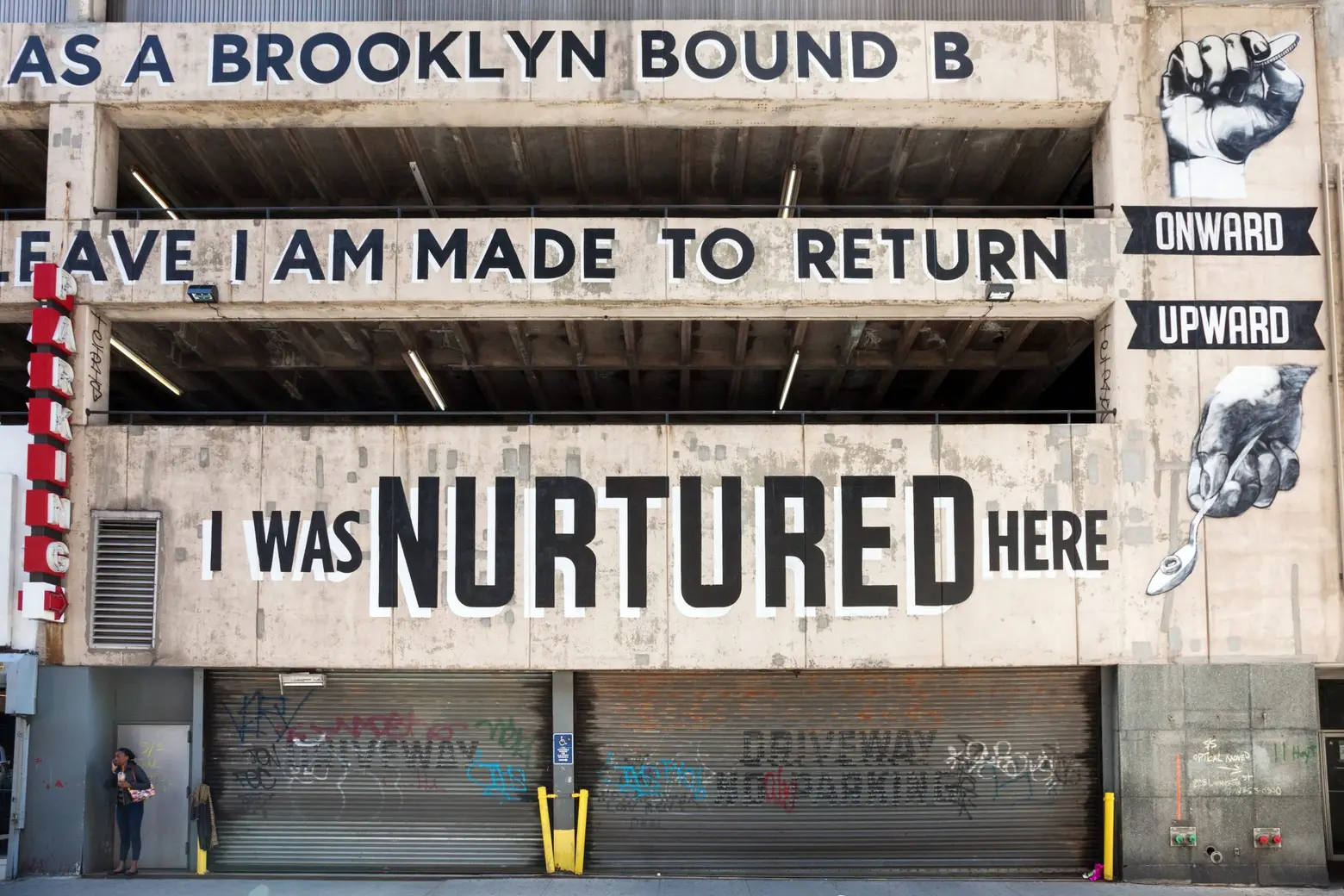

A 2011 photo of “Love Letter to Brooklyn”

A 2011 photo of “Love Letter to Brooklyn”

Your large “Love Letter to Brooklyn” mural in Brooklyn at the Macy’s parking garage on Hoyt Street that you painted in 2011 came down because the property is being redeveloped. Do you want to comment on the big building boom in Brooklyn, especially in the Downtown section?

What’s interesting is that when I got the call to paint the Macy’s garage, it was presented as a temporary project. I had no illusions that this work I was going to create was going to last any longer than it did. We got a perfect run as it lasted for five years. Because it was presented to me as a temporary project, we were able to go a lot crazier and I was a lot freer to do the work that I did. I didn’t even worry about the architecture. We made the architecture disappear in some ways and we highlighted it in other ways. I think that’s something that graffiti does and something that art does and can do. It was a really freeing and thrilling, exciting experience. It was a relief when it was over because it had occupied so much of the landscape and so much of my mental landscape.

There is talk that the work I actually did on the building may rise again because some of it was saved. That has never happened to me before so we’ll see how that goes. Right now, some of the work is packed into crates sitting somewhere in Brooklyn.

That makes me think of Banksy‘s work and how he has been in the news recently. What is a building owner supposed to do when an illegal piece like that is on their building that is being torn down? Is it right that they take it and sell it?

I think so. I feel like it’s kind of a weird, wonderful thing. It’s usually been, for a long time, that when someone paints on your property, it was looked at as an intrusion, as vandalism as some kind. Now that it has turned into some kind of opportunity for money and value, it’s a new phenomenon. It’s really interesting to see and I can’t really comment on it except that this is a brand new unprecedented thing. Maybe there was some precedent, but it used to take 100 years to sort it out and now it takes 37 minutes. It’s interesting; if that is not a crime then maybe nothing is a crime? If you’re not prepared to prosecute Bansky for his obvious unauthorized application of a medium to a surface then maybe nobody is in trouble?

Is there anything you are currently working on that you can tell us about?

I work all the time. I couldn’t even tell you what I am doing tomorrow, much less next week or next month. What I would like to say about the work that I do is that I don’t tell you the weather, I report the news. So we’ll see. You’ll know when I know.

I moved here because I was genuinely moved by New York. I wanted to make it here. There was no real yardstick of success for me other than paying rent and being a part of the city. That’s all I really sought out to do and mission accomplished. It’s fun being here and it’s fun being a part of it and contributing what I can. It’s a place of great energy and it is great to transfer that energy into work and making work. It’s a perpetual motion machine for me.

Ideally, where would you like to be ten years from now?

The place I want to be in New York is right where I am right now. I want to keep doing what I am doing. I am very happy with my lot in life. Everything is working out perfectly. I just want to keep it going. I don’t want to go anywhere. I am already here.

+++

RELATED:

- Designer Sebastian Errazuriz opens up his South Bronx studio full of functional art and furniture

- Where I Work: Go inside Lite Brite Neon’s colorfully gritty Gowanus workshop and showroom

- Where I Work: Artistic duo Strosberg Mandel show off their Soho studio and glam portraits

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.

+++

James and Karla Murray are husband-and-wife New York-based photographers and authors. Their critically acclaimed books include Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York, New York Nights, Store Front II- A History Preserved and Broken Windows-Graffiti NYC. The authors’ landmark 2008 book, Store Front, was cited in Bookforum’s Dec/Jan 2015 issue as one of the “Exemplary art books from the past two decades” and heralded as “One of the periods most successful New York books.” New York Nights was the winner of the prestigious New York Society Library’s 2012 New York City Book Award. James and Karla Murray’s work has been exhibited widely in major institutions and galleries, including solo exhibitions at the Brooklyn Historical Society, Clic Gallery in New York City, and Fotogalerie Im Blauen Haus in Munich, Germany, and group shows at the New-York Historical Society and the Museum of Neon Art in Glendale, CA. Their photographs are included in the permanent collections of major institutions, including the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the New York Public Library, and NYU Langone Medical Center. James and Karla were awarded the 2015 Regina Kellerman Award by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (GVSHP) in recognition of their significant contribution to the quality of life in Greenwich Village, the East Village, and NoHo. James and Karla live in the East Village of Manhattan with their dog Hudson.