Where modernism meets tradition: Inside the Japan Society’s historic headquarters

As a media sponsor of Archtober–NYC’s annual month-long architecture and design festival of tours, lectures, films, and exhibitions–6sqft has teamed up with the Center for Architecture to explore some of their 70+ partner organizations.

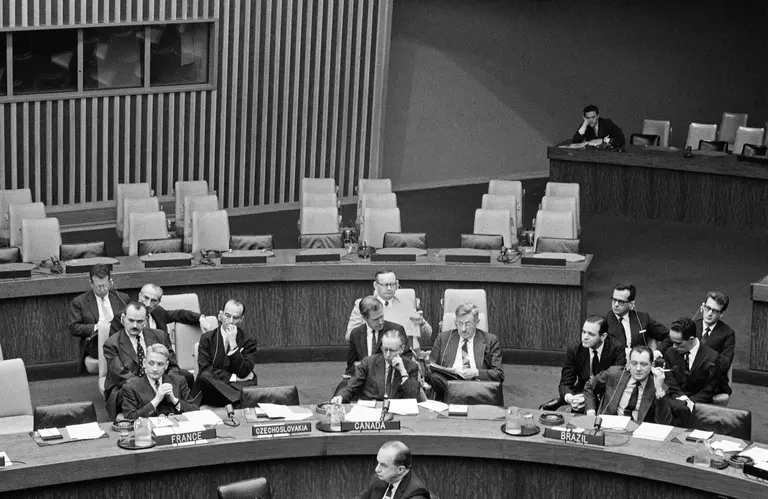

For the last 111 years, the mission of the Japan Society has remained the same: to create a better understanding between the United States and Japan. While strengthening relations originally meant introducing Japanese art and culture to Americans, today in its second century, the nonprofit’s purpose, along with its programming, has expanded, with education and policy now a core part of its objective.

The headquarters of the Japan Society is located in Turtle Bay at 333 East 47th Street, purposely constructed just blocks from the United Nations. In addition to being known for its extensive curriculum, the architecture of the society’s building also stands out. Designed by architects Junzō Yoshimura and George G. Shimamoto, the building is the first designed by a Japanese citizen and the first of contemporary Japanese design in New York City. The structure, which first opened in 1971, combines a modern style with traditional materials of Japan. In 2011, the building was designated a city landmark, becoming one of the youngest buildings with this recognition. Ahead, learn about the Japan Society’s evolving century-long history, its groundbreaking architecture, and its newest exhibition opening this week.

The black exterior stands out from its limestone neighbors

At street level, Yoshimura mixed brass railings and exposed concrete ceiling

The Japan Society formed in 1907, during a visit by Japanese General Baron Tamesada Kuroki, as a way to promote “friendly relations” between the two countries. A group of American businessman established the group to share a “more accurate knowledge of the people of Japan, their aims, ideals, arts, sciences, industries, and economic conditions.”

During this time, New York City’s Japanese population was growing, reaching more than 1,000 in 1900. Community groups started to form to serve this new group, which included the Japan Society. In the beginning, the society focused on publishing books and hosting social events; the group held luncheons and lectures at the former Hotel Astor in Times Square, where a Japanese garden and teahouse was installed on the roof in 1912.

The society suspended all work during World War II. The president of the Japan Society during the war, Henry Waters Taft, resigned immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Activities would not begin again until the Treaty of San Francisco was signed in 1951.

In the lobby, rectangles hold recessed lighting with natural wood baffles

John D. Rockefeller III, a collector of Asian art, revived the organization and became its president in 1952. Michael Chagnon, Ph.D., who has served as the society’s Curator of Exhibition Interpretation since 2015, called Rockefeller a “real humanist who wanted to bridge the cultural divide at the time between the U.S. and Japan and re-founded the Society for that reason.”

Rockefeller oversaw the organization from 1952-1978 and helped shape the Japan Society as it remains today. “The Society’s long-range objective is to help bring the people of the United States and of Japan closer together in their appreciation and understanding of each other and each other’s way of life,” Rockefeller said in 1952. He later founded Asia Society, occupying this new organization and the Japan Society out of a Rockefeller building at 112 East 64th Street, known as Asia House, designed by Philip Johnson.

With a growing membership of 1,500 people, the Japan Society needed a bigger space to keep up with its programming. The organization chose Toyko-born architect Junzo Yoshimura, already a prominent figure in the field, to develop the concept for the new building on East 47th Street. Ground broke on the project in 1969 and construction was completed in 1971.

Key elements designed by Yoshimura include the sleek black facade, the continuous bands of concrete which divide the main elevation, as well as the metal “komoyose” or fencing, the door pulls, and the wood ceiling grilles. Other architectural elements derived from Japanese tradition include metal sunscreens and the use of black and gold, colors associated with some Shinto monuments, as the Landmarks Preservation Commission explained in a designation essay in 2011.

Upon completion, the building received positive feedback. Arts columnist for the New York Times, Leah Gordon, wrote in a 1971 review: “In an area replete with UN Missions and consulates, this building has no seals, no mottos and is distinguished only by a slanted, 3-foot iron fence…It is soon apparent that this is no customary New York architectural atrocity but a sedate, jewel-like structure that, in its quiet way, commands attention.”

Sugimoto designed the two minimalist metal sculptures found in the lobby, found on the upper and lower levels

A renovation was completed in the 1990s by Beyer Blinder Belle Architects to expand the Japan Society, enlarging the library and creating a language center. Overall, 10,000 square feet of space as added across the five-floor building. As a result, the size of the atrium and skylight increased.

Sugimoto also designed this tear-drop sculpture

In 2017, the lobby and atrium underwent a renovation, designed by Hiroshi Sugimoto, a photographer-turned-architect. The two-level serene lobby incorporates many traditional Japanese elements, including bonsai ficus trees, a still pond, and walls made of cedar bark and dried bamboo panels.

The upper atrium platform features custom-made Nara ceramic tile, a flowing waterfall, and a second metal sculpture created by Sugimoto.

There are two bonsai trees

The upper walls of the atrium boast cedar bark and dried bamboo paneled walls; the platform’s material is custom-made Nara ceramic tile

Today, with more space and programs, priorities have shifted. “The emphasis used to be almost entirely on art and now we have a much broader palette of things that we do. I think it keeps things really vibrant,” Chagnon told 6sqft. “We have really vibrant discussions across disciplines at this institution. And as we move forward, that will continue to be the case more and more.”

The newest exhibition at Japan Society, “Yasumasa Morimura Ego Obscura,” opens on October 12. Running until next January, the show examines Morimura, one of Japan’s greatest pioneers in contemporary art, and his intertwining of post-war Japanese history with his own biography.

The society is hosting a slate of related programs, including lectures, a book club with a book chosen by Morimura, and a one-night-only live performance by Morimura called Nippon Cha Cha Cha. And there will be an “Escape East” happy hour to celebrate the opening week of the new exhibition, accompanied by live music and complimentary sake tastings.

RELATED:

- Where I Work: Gregory Wessner organizes NYC’s biggest ’Open House’

- Where I Work: Chef Bill Telepan takes us inside a ‘farm-to-classroom’ hydroponic garden

- Where I Work: The trio behind Van Leeuwen ice cream show off their pastel-painted UWS shop

All photos taken by James and Karla Murray exclusively for 6sqft. Photos are not to be reproduced without written permission from 6sqft.