Why people hate revolving doors and how to curb the phobia

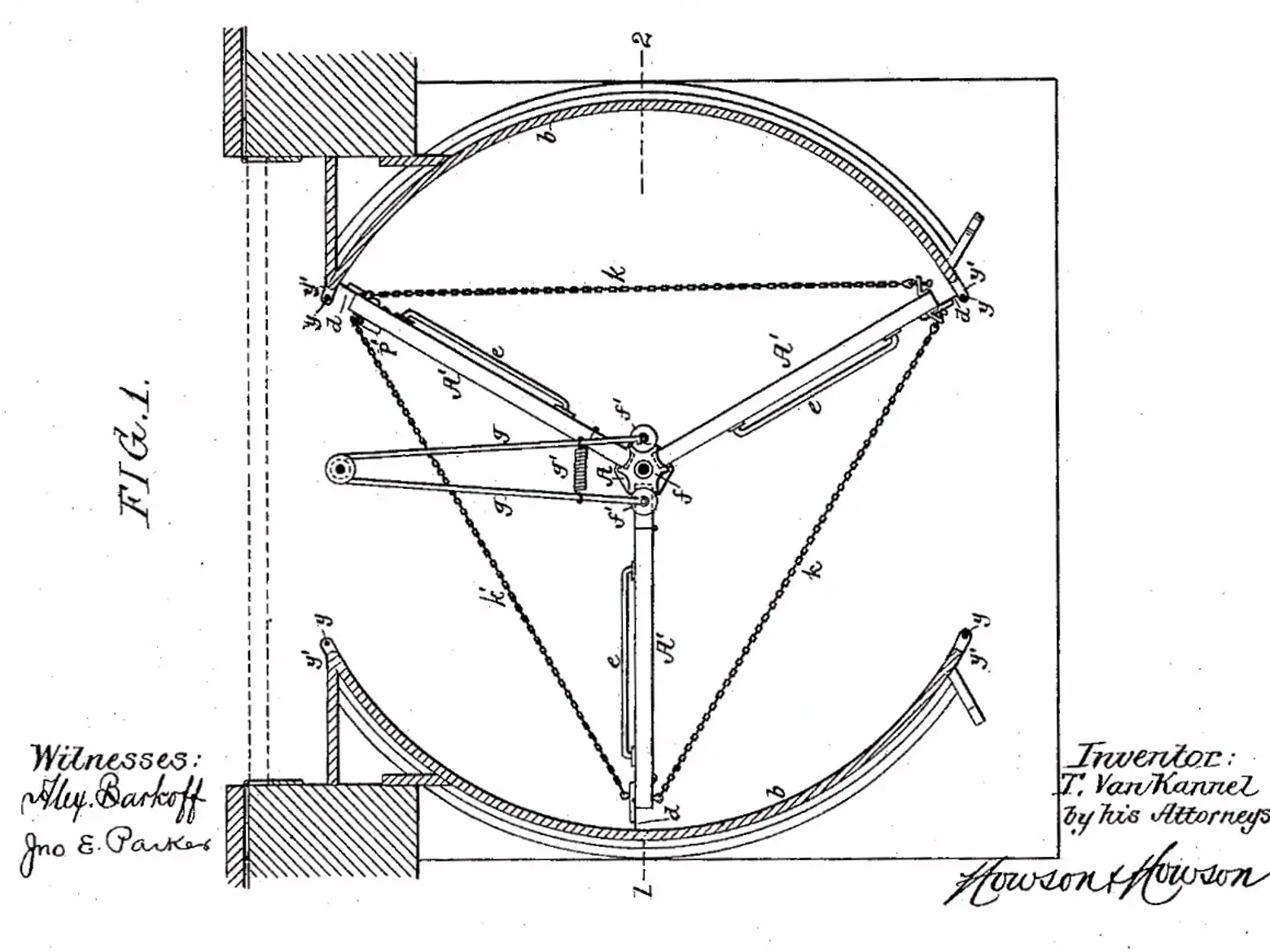

You know that moment of awkwardness when you’re sucked in to a totally irrational game of chicken with up to three other human beings while attempting to do something as simple as enter your office building through an innocuous-seeming revolving door? While it was reportedly first patented in 1888 by a man who couldn’t deal with having to hold regular swinging doors open for the ladies, the revolving door comes with its own means of sorting us according to levels of everyday neurosis.

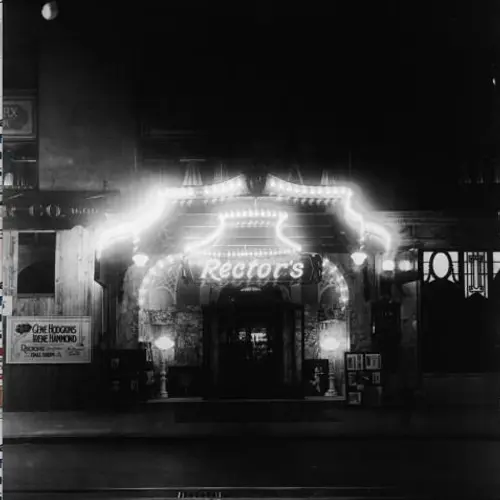

The first revolving door was installed in a restaurant called Rector’s in Times Square in 1899. And that’s probably when people started avoiding it. Will some part of me get stuck? Do I have to scurry in there with someone else? 99% Invisible got their foot in the door and took a closer look at how this energy-efficient invention still gets the cold shoulder and how to fight the phobia.

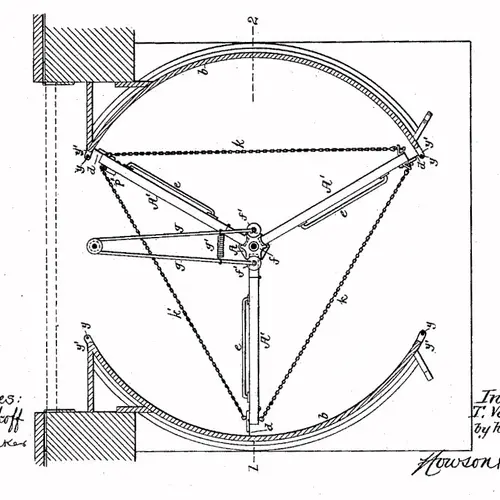

Theophilus Van Kannel’s patented revolving door

The revolving door was a great solution for “keeping dust, and noise, and rain and sleet and snow from entering buildings.” Because they never open, they prevent the free exchange of air from the outside to the inside (except in the chamber of the door and maybe a little around its weather stripping), making them more energy-efficient: Revolving doors exchange eight times less air than swinging doors, which could save thousands of dollars in energy costs per building per year.

On the other hand, some people are terrified of them. A group of MIT students investigated this phenomenon in 2006, looking to put a number on how much energy would be saved if the revolving door was used to its full potential. What they ended up noting, however, was that only 25 percent of people entering the building used it. The students put signs up around the school instructing people to use the revolving doors to save energy. What followed was a whopping 30 percent increase in revolving door use–up to 58 percent.

A few years later, Columbia University graduate student Andrew Shea repeated the experiment and found, again, that only 28 percent of people were opting for the spinner. Shea, whose thesis involved the subject of designing for social change, developed a super low-tech “revolving door kit” consisting of–you guessed it–a sign briefly asking folks to, for heaven’s sake, use it. Usage increased immediately.

Revolving door in Chinatown, Susan Sermoneta via flickr.

Tweaking the sign was the next step. Adding some of Columbia University’s branding in the form of recognizable colors and graphics upped revolving door use to 71 percent–43 points higher than the original number of users.

An intrepid pair of 99% Invisible producers gave the admittedly informal experiment a whirl recently in a downtown Oakland building. Same result. The revolving door sat nearly unused. They slapped up a sign with an arrow and a simple explanation. The number of users doubled in five minutes. For whatever reason–maybe people thought the swinging door was broken–nearly 30 percent more people followed the signs instructions.

At the Marriott Hotel in Oakland, an optimized revolving door is the visual focus of the entrance; it revolves automatically and has larger compartments to accommodate you, a fellow entrant and all of your social phobia. This combination tends to nudge people toward the revolving door instead of its swinging sidekicks.

Download and post this sign on a revolving door near you, courtesy of 99% Invisible

Because a mass-redesign of all the world’s revolving doors may be a while off, the radio show’s producers have designed a “revolving door action kit” that you can download (free, tape not included) and implement in the name of taking small steps toward sustainability.

[Via 99% Invisible]

RELATED:

- Design Firm Reimagines Neglected Space Under the BQE as a Food Court and Sports Center

- Don’t Look Up: Would Traffic Signals in the Pavement Protect NYC Phone Gazers?

- Six Architects Reimagine the MetLife Building As an Eco-Friendly Tower of the Future

Lead Image: Marcel Oosterwijk via flickr.